Hyderabad, TELANGANA :

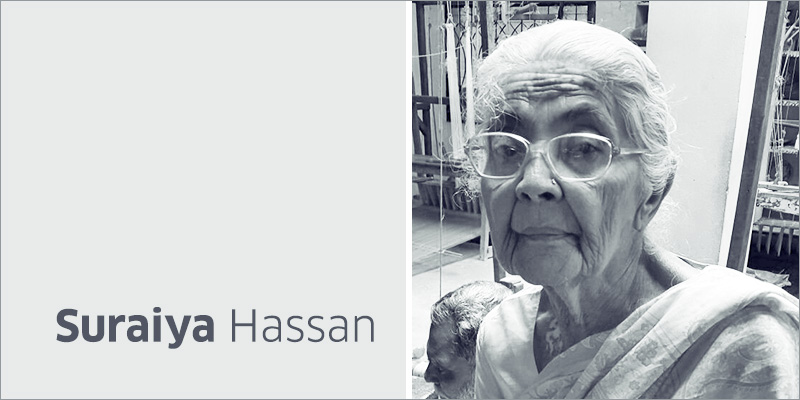

“Mrs. Suraiya Hassan?”

“Haan ji, bol rahi hoon. Boliye..”, the grand old lady of Indian weaving greets me into the conversation. Engaged in revival work of four different textile forms of Aurangabad, Suraiya has a fascinating tale to narrate.

Her journey began soon after she finished her Intermediate. Suraiya joined the Cottage Industries Emporium, a government institution where she learnt the art of salesmanship and production of textiles and handicrafts. It was a great learning experience spanning well over four years, says Suraiya.

It was while working here that a professor from a foreign country, Suraiya says it would be London, came to their Emporium and she was put in charge of showing her around. “She touched and felt everything and was so impressed with me describing the importance of each and every fabric and handicraft product that she thought I was wasting my time here,” says Suraiya on a lighter note recalling her toddler steps into the weaving industry. Eventually it was this lady who introduced Suraiya to her mentor Pupul Jaykar, of the Handloom Handicrafts Corporation of India in New Delhi.

It was a move Suraiya had not contemplated in life and it truly got her where she perhaps wanted to be. “Maine kabhi aisa socha nahi tha, lekin ye ek achchi opportunity thi, so I decided to go along,” says Suraiya (I had never thought of such a career move but when opportunity came knocking, I didn’t say no).

It helped that she had her uncle (chacha) Abid Hassan Safrani living in Delhi. He was with the Ministry of External Affairs initially and at one point was personal secretary to the legendary Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, recalls Suraiya.

Her association with Bose’s family

Suraiya was soon introduced to the Bose family through their ladies. From casual visits, the journeys

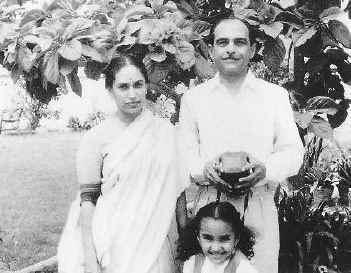

Little did she understand the importance of being married to Bose’s nephew except that Aurobindo too was a busy politician. “He was a trade union secretary with many big companies,” says Suraiya of her husband. She however, never got a chance to meet Subhash Chandra Bose.became personal and Suraiya got to know the family from close quarters. She then got married to Aurobindo Bose, Subhas Chandra Bose’s nephew.

From Delhi back to Hyderabad

After superannuation, Abid Hassan moved to Hyderabadand bought some land there. He was the one who called Suraiya back to the Nizam’s city and asked her to set up an independent handloom production unit.

“I wasted no time and got to my hometown to set up this unit. It was an exhaustive task but I would say worth the effort,” says Suraiya. It was here that she started work on the revival of four signature Persian fabric forms native to Aurangabad – Paithani, Jamawar, Himroo and Mashru. Thus was born Suraiya’s Weaving Studio, Suraiya’s weaving unit in Hyderabad.

During my visits to Aurangabad, I had seen many artisans work tirelessly on keeping this art alive, but in a very small way, often at their own homes. I therefore decided to make this sector a little organized in the hope that this dying art will have people following it

While she concentrated on her art, her husband used to visit her in Hyderabad when he had free time on his hand.

She is still in touch with the Bose family though the visits have dwindled in number after her husband passed away.

Social enterprise

Suraiya selected a group of people to pass on her art. It was the widows, with no place to go to and children to feed that she thought would be her right target audience. “I used to sit with them for hours together and help them pick up the nuances. To train one artisan easily takes close to 3-4 months on an average and I later got an expert to help me with the training part. Doing it alone was becoming a Herculean task,” says Suraiya.

While she created an opportunity for widows to pick up the art, she helped by setting up a school in the same compound for their children. Called the Safrani Memorial High School, this institute houses classes for students from Nursery to Std 10, where children of her artisans attend school free of cost.

Aged 84 now, Suraiya says she has lots of work yet to do. When she is not supervising the work of her artisans, she goes to teach students in her school. She takes pride in the fact that they have all performed well and some have even gone abroad.

Well this love for education is not by chance, Suraiya says she would have inherited it from her father. He after all was the proud owner of Hyderabad Book Depot on Abids Road, most likely the first book store in Hyderabad which stocked foreign publications.

source: http://www.her.yourstory.com / YourStory.com / Home> Her Story> Inspiration / by Saraswati Mukherjee / January 12th, 2015