Bengaluru, KARNATAKA :

Anjum is a self-confessed foodie, and loves cooking. In fact, she recalls, it was this love and talent that led to her meeting Omer at the restaurant: “I used to bake a lot, and market my cakes and pastries to earn my pocket money, to spend on music and clothes”

He is a descendant of the royal families of Bhopal, Pataudi and the Paigahs of Hyderabad, she is the sister of the tycoons who run one of Bengaluru’s biggest realty companies. They have now joined hands to raise the level of living in the Prestige Group’s apartments and resorts-she designs and executes the interiors, while he has set up and runs the group’s hospitality vertical

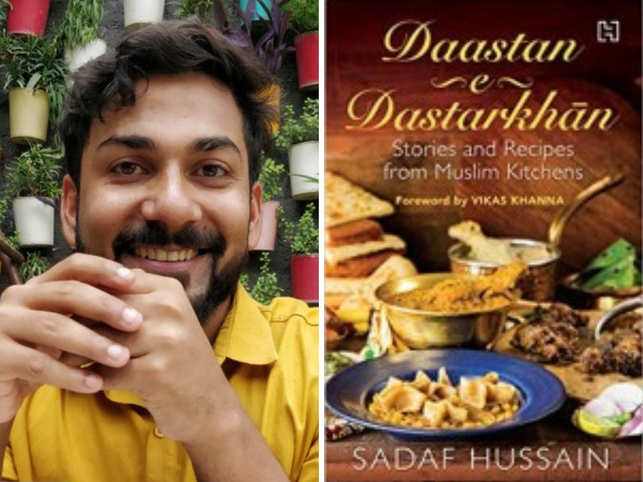

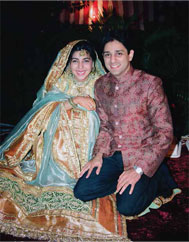

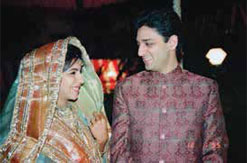

Nawabzada Omer Bin Jung and Anjum Razack met on a blind date. Well, not exactly a blind date, they say: “Actually, we were set up!” says Anjum, and Omer agrees. “But she picked me up!” he adds, with a twinkle in his eye. He is being literal: “I had no car, and used to roam around in buses and auto-rickshaws when I was working with Wipro.” So this young woman whom he had never met came to his office and gave him a lift.

Recalling the incidents of more than a decade ago, husband and wife keep bickering good-naturedly and correcting each other over details. The story that emerges is that a friend of Anjum’s said she wanted to meet her-at Casa Piccola, a restaurant to which Anjum used to supply cakes she baked. “And will you please pick up this guy Omer on the way? I want to meet him too,” she said. So an unsuspecting Anjum drove an equally unsuspecting Omer to the restaurant, where they sat and waited for the friend. When some time passed and she didn’t appear, they realised what had happened.

Was it love at first sight? “I don’t know if it was love, but I knew immediately that this was the guy I was going to marry!” she says. “My mother had always told me: ‘You should know what kind of boy you should bring home to meet me!’-and that afternoon I told her I had met the right man.”

Omer, for his part, “Enjoyed being the hunted, for a change”. They didn’t meet, or talk, for a month; but one day-just before Valentine’s Day, Anjum remembers-she and her friend were driving somewhere, when they spotted Omer walking. “We stopped, said ‘Hi!’ and gave him a lift.”

Things didn’t take very long after that. “My family doesn’t have the time for trivia!” Anjum explains. “I told my mother as soon as I got home that I had met the boy I was going to marry. I mean, we were two eligible young people in the same town. He was not of our caste of traditional business people, which was actually a plus point in his favour! Our families met, and I went through the various shredders his family put me through, then picked up the pieces-and we got engaged, then married in the next eight months.”

“We were two eligible young people in the same town. He was not of our caste of traditional business people, which was actually a plus point in his favour! Our families met, and I went through the various shredders his family put me through, then picked up the pieces−and we got engaged, then married in the next eight months.” − Anjum

A few months before the marriage, they went to see Omer’s grandmother: “That was the first time I took a break from work,” she says. “Morph was still a one-person company, with only a set of carpenters to supervise. When we came back, I was broke, and went straight back to work. Side by side, I set up home and pottered around there, too.”

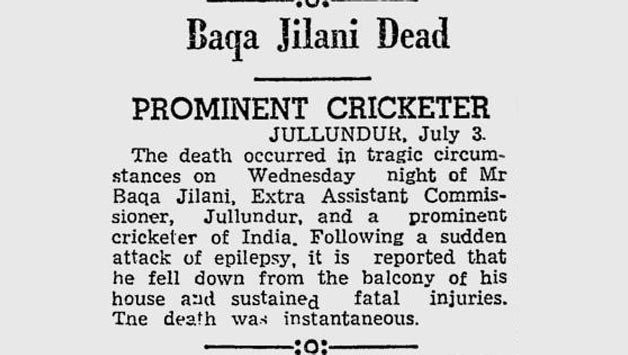

Anjum, the sister of the Razack brothers who run Bengaluru-based construction major Prestige group, is an entrepreneur in her own right: she set up Morph Design Company (MDC), which she runs as its Managing Director. Omer, who heads Prestige’s recent diversification into the hospitality business, comes from a long line of rulers-from the Paigahs of Hyderabad on his father’s side to a royal pedigree on his mother’s. “I have an interesting and diverse lineage. My maternal grandmother was the ruler of Bhopal with its matriarchal system. She married the Nawab of Pataudi, which was a much smaller kingdom, but both became our family’s houses. My father’s people were Prime Ministers to the Nizam of Hyderabad.” The Paigahs are a family of the senior aristocracy of the erstwhile Hyderabad State, with each of them maintaining his own court, individual palaces and a standing army of 3,000 or 4,000 soldiers.

Anjum, on the other hand, was what she calls ‘a one-woman army’ in a male-dominated business when she joined her brothers in 1993 and set up MDC. That ‘one-woman army’ has grown in 23 years to a Rs. 200-crore, 30-member team; but she continues to work hands-on with every project. “They are a bunch of kids-we are a young, growing office,” she says. “Besides, I love what I do-and I always put in 100 per cent into any assignment, because you always get only what you put in. I am also an obsessive perfectionist and would never deliver to a client what I wouldn’t live in myself.”

She had found, when she finished school, that she was in a ‘strange situation’ with not too many career options for a girl of her background-a Kutchi Memon in a typical business family, but one whose father had believed in education for his daughter as well as his three sons. “My parents have always been very aspirational for all their four children,” she explains. “We were all given education, encouraged to travel and grow-all against the norm in our community.” So after her B Com, she did a course in interiors with paint manufacturer Jenson & Nicholson. She then got a job with an interior designer in the early 1990s before joining the family business. “I jumped into the ocean headlong, without even knowing how to swim!” she says. “It was only the challenge that kept me

MDC, which she established soon after that plunge, not only creates all the interiors in the Prestige Group’s developments, but also offers consultation, comprehensive planning and end-to-end design solutions for a range of other select clients for both their existing structures and new projects. She is also rightfully proud of the fact that her brothers Irfan Razack, Chairman and Managing Director of the Rs. 4,700-crore Prestige Group, and Rezwan Razack, who is Joint MD, never gave her any special privileges in business. “Even though we are a very close-knit family,” she says. “Morph is my very own, Prestige is my client. I charge design and project management fees, and for the furniture and other material I supply from either my own manufacturing units or those from whom I source them.” She does, however, describe working with family as putting her ‘between a rock and a hard place’ very often.

“My big idea was to reach out to the discerning interior design market, be it luxury or aspirational, and provide my clients with a lifestyle that they would enjoy,” is how Anjum how explains the way she approaches her work. “I wanted to introduce discerning customers to living spaces that represent and reflect their individual taste and stay relevant through changing times.” Designing an interior space, she points out, presupposes that “A design metaphor will reveal itself in every object, colour, finish and patina”. Obviously, when the idea finds expression and rhythm in such detail, the natural outcome would be a space made distinctive by its very uniqueness. “That,” she adds, “is why I do not just stop at designing the experience of an interior space, but also construct or create most of the objects that shape the design.”

“I went to boarding school at Sanawar, then Hindu College in Delhi and the London School of Economics. When I came back to India, I decided to move to Bengaluru instead of Hyderabad−it was a new city as compared to Hyderabad, and I could do anything here with its own level of decadence! Besides, my elder brother was here too” − Omer

“Good taste in interiors has come of age. The challenge lies in the fact that often, the notion of interior design stops at the placement of attractive objects in a well-designed room. While that is a mandate we can serve with ease, we challenge ourselves to give our customers much more. This we do by shaping their experience of interior space, through manipulation of spatial volume, as well as surface treatment. So, while apartments today are predicated on the optimal use of space and uniformity, our challenge is to create a unique interior space in a structurally similar landscape,” she says.

“We have also integrated backward to create a super-large vertical, with project management, sourcing and a trading company-and now even furniture manufacturing. We create 90 per cent of all the furniture that is provided in any Prestige construction.”

From its beginnings as an in-house interior design subdivision, Morph has morphed into a fully integrated interior design firm that executes and handles projects for external clientele, too. It provides a one-point solution from design, creating a portfolio of work across apartments, villas, clubhouses, spas, resorts and hotels. Hotels, resorts or serviced apartments. “All of these need to be addressed very differently from one another,” Anjum explains. Along the way, the company has worked with globally renowned architecture firms like Dileonardo, Woods Bagot, HBA, MAP and SRSS, and executed projects as large as 2.5 million sq ft (nearly a quarter million sq m). “We have also won a lot of awards, in different areas of our work. My brothers look at me differently now!” she adds.

Describing herself as an entrepreneur at heart, not satisfied with interior design alone, Anjum says this is why she vertically integrated the manufacturing process by setting up state-of-the-art in-house factories over two decades ago, to cater to the different design sensibilities of customers, from traditional, classic to the more contemporary, experimental and eclectic. “Our products are also designed to give our clients great value for money across the entire product spectrum,” she adds.

“From a process perspective, everything from concept, drawings, prototyping, to the final production of each and every piece of furniture that we use in our projects is backward integrated,” she explains. “Our external dependence is minimal and allows us to achieve unmatched quality giving us the ability to create truly bespoke interiors, where each detail is created by us. Having control over customisation and production, we ensure that our design process is a constantly evolving and dynamic one”

“The journey has been tough-but a good tough!” Anjum smiles. “The biggest chip on my shoulder is that I didn’t go to design school. But I love working, and I have been loyal to my work.” She did, however, take a course in designing at Cornell University. “I firmly believe that you must always start from the back operations to be strong. There was a sad lack of originality and quality in the market-that’s why I started my furniture business with visits to China, Italy, Germany, Austria and Burma, getting the best rates at which I could import what I needed for each project.”

With this bottom-up organisational design approach, Anjum has been responsible for business development, strategic planning, diversification, and project management along with all other key executive functions. Her work is inspired by a diverse set of influences, both traditional and contemporary, and she references the Deco and Nouveau period styles as being particularly impactful. Firmly believing in the importance of constant evolution for prolonged success, she doesn’t hesitate to incorporate innovative materials into her projects, work with young artists and experiment with all aspects of execution.

“Some things are non-negotiable! For instance, no phones are allowed at meal time. The kids get a platform to talk to each other and us, about things that would otherwise get buried in their busy lives. There are some ground rules, and they stick to them” – Omer

“My two new factories involve a huge investment, which means I will probably be able to break even only two or three years,” says the businesswoman, now 49. “The state-of-the-art factories have been conceived with a lot of mechanisation-manufacturing wooden joineries, handcrafted furniture, modular furniture, wardrobes, windows and kitchen assemblies. MDC also has a unit which specialises in developing soft furnishings.” Today, Anjum can proudly claim that she has nurtured MDC into one of the country’s most respected décor studios with globally recognised clientele and numerous national and international awards to its credit.

Talking of challenges, Anjum says the biggest one has always been the debate between functionality and design and how to marry them: “The aspirational customers have a relatively limited budget and want products that are aesthetically pleasing, have longevity and are easy to maintain. We have strived to address the needs of this particular segment and are happy to say that we have managed to achieve it to a very large extent.”

The other challenge, she says, is to provide aesthetic designs to any area. “Everyone deserves appealing spaces, regardless of its size,” she says. “We, at Morph Design Company, excel in providing just that.” Pointing out that the business also involves effectively executing two opposing areas of demand: the high-volume kitchen and wardrobe assemblies on one side, and the need for personalised and exclusive products that cater to the individual versus the mainstream on the other, she credits the nature of these challenges is what keeps her and her team striving for excellence.

Anjum is a self-confessed foodie, and loves cooking. In fact, it was this love and talent that led to her meeting Omer at the restaurant: “I used to bake a lot, and market my cakes and pastries to earn my pocket money, to spend on music and clothes,” she says. “Casa Piccola was one of my biggest customers. And so, when my friend Goga suggested meeting her there, I didn’t think it was at all strange.”

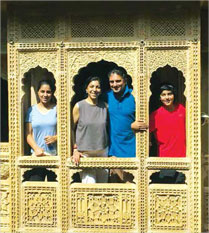

She also reads voraciously and loves to travel-collecting art and antiques from the places she visits. Her husband shares her interests-and so they pack their bags and heads off to different locales in India and abroad. The couple began with a two-week honeymoon in Africa; and because he loves surprising her, he recently took her on a road trip from Budapest to Prague via Vienna-“He made me drive!” she mock-complains- so that he could treat her to a four-hour meal at a three-star Michelin restaurant on the way.

Nawabzada Omer Bin Jung, formally designated Executive Director, Hospitality-Prestige Group, is also the Founding Managing Director of Prestige Leisure Resorts (P) Ltd. With three decades of experience in hospitality, he is currently spearheading the Group’s foray into hospitality. “I went to boarding school at Sanawar, then Hindu College in Delhi (where he was a gold medallist in his BA, Anjum intercedes) and the London School of Economics,” he says. “When I came back to India, I decided to move to Bengaluru instead of Hyderabad-it was a new city as compared to Hyderabad, and I could do anything here with its own level of decadence! Besides, my elder brother was here too.”

After a couple of years in the finance department of Wipro, he joined his brother who has a resort in Bandipur. “Actually, it was a just a Club House; now it has been converted into the Northwest County resort,” he explains. In 1997, three years after he married Anjum, he floated the idea of helping his brothers-in-law take their construction business into resorts. “There has been no looking back since then,” he says. “We also have food courts in malls, we run franchises for Subway, Falafel and others… it’s a good mix.”

Adds his Begum: “It wasn’t an asset class at all – it was Omer’s brainchild.” He explains that because the business was totally in real estate, it had no assets on its balance sheet because all its projects were sold. “Assets are always good to have,” he says. “That’s where the discussion started. And we began to become more asset heavy.”

And so, having established Prestige Leisure Resorts, Omer now aims to set up international spas, city hotels, resorts and food courts all over India in the coming years. He is amply qualified: besides his gold-medal BA and his post-graduate Diploma in Business Studies from LSE, he also has a post-graduate Master’s Degree in Business Administration with a specialisation in Marketing, as well as a Certification in Strategic Management by Cornell University School of Hotel Administration, US.

“To excel in any field, one needs to be a team player. Managing people and ensuring employee and customer satisfaction is an integral part of being a success. We are a service-oriented industry and it is our team’s talent that decides the success of our work” – Anjum

At Prestige, Omer has been instrumental in conceptualising and tying up with Banyan Tree Hotels and Resorts, Singapore, for one of Bengaluru’s most beautiful spa resorts the world-class Angsana Oasis Spa & Resort; the Angsana Oasis City Spas at UB City; Hilton International for the Conrad, Bengaluru; Oakwood Asia Pacific for the Oakwood Premier Serviced Residences at UB City and the Oakwood Residences-Forum Value Mall, Whitefield as well as the 3.4-hectare Sheraton Grand Whitefield Hotel and Convention Center in the group’s Shantiniketan project; the JW Marriott Hotel in Prestige Golfshire below the Nandi Hills and the 23-storey Conrad Hotel overlooking the Ulsoor Lake. He is also the brain behind the Transit food lounge at The Forum, Koramangala.

“We have introduced some of the most reputed international brands in the world to South India, such as the Hilton Group and Marriott International for hotels; the Banyan Tree for resorts: our Angsana Oasis Spa & Resort is managed by Banyan Tree Hotel & Resorts, Singapore. We also have the Oakwood Premier Prestige Serviced Residences in our landmark development, UB City, as well as in Whitefield,” he points out. We launched our hotel, ‘The Aloft’, in Prestige Cessna Business Park in 2014 in association with Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide.”

Anjum also shares some of the secrets for her success: “To excel in any field, one needs to be a team player. Managing people and ensuring employee and customer satisfaction is an integral part of being a success. We are a service-oriented industry and it is our team’s talent that decides the success of our work. Therefore, it is very important to ensure that your team is motivated and happy. Finally, it is crucial to have in depth knowledge of both the industry and the products, which is only possible if you have a genuine passion for your work, as only then will you constantly strive towards perfecting your art.” Apart from this, it is paramount to believe in yourself, your abilities and objectives and have the right conviction. Life is full of complexities. Keeping things simple and using a straightforward approach helps unravel intricacies.

Her role models are her father Razack Sattar, an enterprising entrepreneur who started Prestige Fashions way back in 1956; and after his passing, her three elder brothers Irfan, Rezwan and Noaman have been her mentors, propelling her to success. “They have inspired me to keep pushing myself to achieve greater heights and are a source of constant motivation for me,” she explains. She too wants to carry on this culture of helping others: “I want to create a platform for young interior, product and furniture designers whom I will launch and mentor, to help hone their skills and realise their dreams,” she concludes.

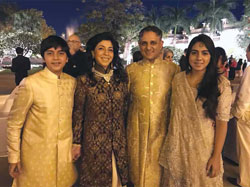

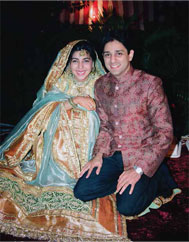

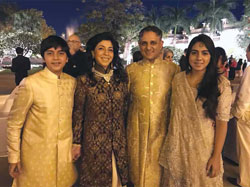

The Jungs’ daughter Zara was born in 1999, and their son Ayaan five years later. “Kids never worried me, I enjoy them at all ages,” Omer says. And Anjum gives him ‘100 per cent for being an outstanding father’, saying: “He handles the children so well. Till date, he puts Ayaan to bed every night. He also takes his just-into-his-teens son on a fishing and hunting trip for two weeks every year.”

How did they manage everything: work, which is often 24×7, parenting- which is 24×7-and getting away for holidays? “We have a very good support system in the family,” Anjum says. “My mother has always been a big help, even though she was looking after my father who fell sick in 1995 soon after our marriage, and never recovered till he passed away in 2004. But I too never thought of multi-tasking-handling work, kids and home-as a problem. Of course, we had good staff: our maid and driver are very devoted to the family.”

Both of them are religious, and practise their faith: “We pray, fast, and go for Haj,” Omer says. Adds Anjum: “My mother was very pragmatic in her approach to Islam, though my father was more ritualistic.” According to Omer, their prayers are more for thankfulness than to ask for something. “We are so blessed,” he points out. “We have been to Arabia few times. So yes, we practise-but at the same time, we question.” Says Anjum, simply: “I like the balance.”

And the children are, fortunately, not yet growing away from their parents: Zara has her own life, but is at the same time totally plugged into the concept of family. “Some things are non-negotiable!” says Omer. “For instance, no phones are allowed at meal time. The kids get a platform to talk to each other and us, about things that would otherwise get buried in their busy lives. There are some ground rules, and they stick to them.” They are not totally happy going away on their own, but can still manage independently all over the place. Zara, for example, went to Oxford on her own for a summer course, Anjum points out. “She organised her own travel, and did very well there too-she came first in her class.”

All four of them spend a lot of time together as a family, even on holidays. “We don’t need to go out and mingle, we are very content by ourselves,” she says. “Three holidays every year are a must. We go away for the summer, Dussehra and Christmas vacations.”

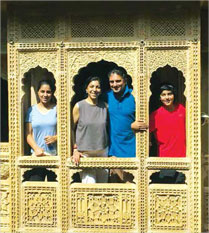

Last year, Ayaan came up with a surprising question: “Why must we always fly abroad? Why don’t we take a holiday in India?” Says Omer: “Both of us had found it very difficult earlier to wrap ourselves around a holiday in India. But after my son asked this question, we decided to go to Rajasthan-it was fun. We like our luxuries-but besides the Michelin restaurants, we also like to eat local food in different places. For example, we had a great meal of daal-bhaat at a truck stop in Rajasthan.” They didn’t of course, exactly rough it out in the desert: his royal connections ensured that they had the best hospitality in the local palaces. “India is brilliant!” Anjum says.

“Even though both of us are busy, we like to invest time in the kids as well as for ourselves together,” Omer says. “Of course, there is always a trade-off, in terms of earning less than we could if we concentrated only on our work or business. The question of what has priority in our lives keeps changing. But health, time with the children, family time, religion-they all take precedence.”

In addition to all this, Omer manages to find time to play cricket-coming as he does from a cricketing family-and golf, besides his angling and hunting which again is a throwback to his family’s traditions. “He is a ‘renowned shot’!” Anjum says with obvious pride. That, he explains, is a qualification that enables him to participate in national shooting championships. He is also interested in football, and took his son to watch Manchester United play a home match on Boxing Day last year: “There must always be an element of surprise in what I do,” he grins. “I had planned the itinerary for that trip with a gap of one day, which the rest of the family were clued in that they didn’t even notice! That was the day I just took off with Ayaan for the match.”

“We have introduced some of the most reputed international brands in the world to South India, such as the Hilton Group and Marriott International for hotels; the Banyan Tree for resorts: our Angsana Oasis Spa & Resort is managed by Banyan Tree Hotel & Resorts, Singapore” — Omer

How have they found the much-vaunted “entrepreneur-friendly” systems introduced by the government, especially that of Karnataka where they operate? “Well,” starts Omer, “When we started the hospitality business, we needed a total of 29 licenses… But today,” he pauses dramatically, and adds: “We need 29 licenses, still. The license raj has not gone away, it is only that we have learned to handle it more gracefully. The pain is still there. But we had the luxury of assets like easy access to loans and, our families.”

Anjum’s story is slightly different. “I started as a woman entrepreneur,” she explains. “That angle worked for me.” She still loves to cook; and, Omer says, “People love to be invited to our home for a meal.”

“We never have the time to get bored,” Anjum says. “We’ve practically grown up together, through our 23-year marriage. Both of us are the same age, so that’s almost half our lives. We have so many things in common; like, we were reading the same translation of the Quran, or The Little Prince, at the same time-but we are still as different as chalk and cheese. Of course, his stupid sense of humour sometimes irritates me, but…” To which her husband grins. And she adds: “I promise you, I wouldn’t want to grow older with anyone else but Omer.”

source: http://www.corporatecitizen.in / Corporate Citizen / Home> Cover Story / by Sekhar Seshan / Vol.3, Issue No. 2 / April 15th, 2017