NEW DELHI , INDIA :

Ruby Lal’s book gives a new life to Nur Jahanas Jahangir’s co-sovereign, a position never held by any Mughal woman

The polemical potential of Ruby Lal’s new book is apparent from its title, even before we get to the text proper. Empress: The Astonishing Reign Of Nur Jahan takes the spotlight away from Jahangir, one of the Great Mughals, to shine it on his 20th and favourite wife, who, as Lal proposes, not only scaled untold heights during his reign but also announced herself to be his “co-sovereign”.

“Scholars have for some time acknowledged her power, almost in bullet points, but never in any concrete way thought through it,” says Lal, who teaches at Emory University in the US, on email. “There is still the tendency in scholarly and other writings to lock Nur’s power in a romantic story with Jahangir: in fact, that romance becomes the explanation for her rise.”

While there may be more than a grain of truth in Jahangir’s devotion to his beloved spouse (it has been the subject of several movies), Nur Jahan’s political acumen and gallantry make her phenomenal career trajectory seem inevitable. Lal begins, for instance, with a spectacular scene of a hunt, in which a musket-bearing Nur Jahan kills a man-eating tiger in Mathura, where the royal cavalcade made a stop on its way to the Himalayan foothills in the autumn of 1619. Nur, 42 at the time, had been married to Jahangir, her second husband, since 1611. It was a fate her parents, Ghiyas Beg and Asmat Begum, could never have foreseen when their daughter, Mihr un-Nisa, was born in 1577 by the roadside outside Kandahar, as they fled their home in Herat.

Hounded out of Persia due to religious persecution, Beg sought Akbar’s patronage in the late 16th century, and it was generously provided. Eventually decorated as I’timad ud-Daula, or the Pillar of the State, by his regal son-in-law, Beg went on to assume the highest rank in Jahangir’s service. His family did well by the Mughal rulers too. Beg’s son, Asaf Khan, would turn out to be the future emperor Shah Jahan’s father-in-law. But it was Beg’s daughter, Mihr un-Nisa, honoured by her royal husband as Nur Jahan, or the Light of the World, who assured him a place in history.

If Nur was exemplary for being the first woman in the subcontinent to exercise direct executive privilege, she was doubly impressive for achieving such a status as a rank outsider. “Remember, she was not a Mughal by bloodline,” says Lal, “not like Queen Elizabeth I (of England) or Queen Christina (of Sweden), who were from royal families.” Nur’s elevation, in the context of her times, was certainly unprecedented, though women in the Mughal harem, especially the elders, often did act as confidantes, advisers and counsellors to the emperor.

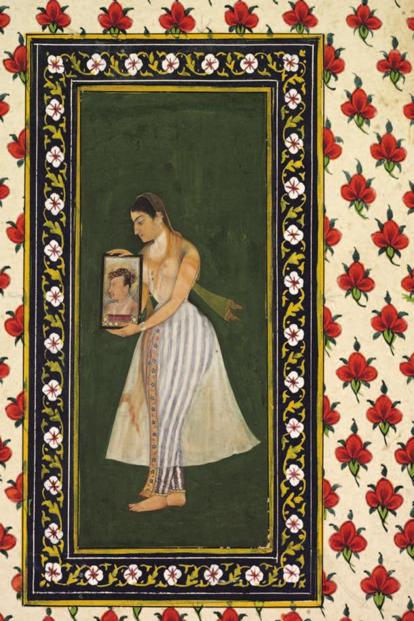

Gulbadan Banu Begum, Babar’s daughter and Akbar’s aunt, and Hamideh Begum, Akbar’s mother, were matriarchs to reckon with. Nur’s mother, a lady of refinement and education, was credited with the discovery of an itar (perfume) while boiling petals to make rosewater. But no one went as far as Nur, who made appearances on the imperial balcony, issued firmans (orders) and had coins embossed with her own image—all of which were kingly prerogatives. A skilled marksman, Nur would also lead an army later in life in a failed attempt to rescue Jahangir when he was held hostage by one of his aggrieved officials.

Although the Mughal harem has claimed the attention of scholars, Ira Mukhoty’s recent feminist history, Daughters Of The Sun: Empresses, Queens And Begums Of The Mughal Empire, breathed fresh life into it, making it accessible and emotionally absorbing to the common reader. Lal’s book, replete with research but also narrated with a sense of drama befitting a novel, complements it beautifully.

With the paucity of first-person testimonies from the women of the era, it is not surprising that much of the narrative of Empress is pieced together from observations left behind by Nur Jahan’s contemporaries in the footnotes and interstices of archival documents. “The records are plenty and rich,” says Lal, emphatically, “it’s how you approach the courtly documents, paintings, poetry, coins, architecture, and even legends.”

The British diplomat Thomas Roe, for instance, who visited Jahangir’s court to woo him for exclusive trading rights, was piqued by Nur’s bossiness. But her charisma, intelligence and stately demeanour didn’t escape him. “Noormahel fulfils the observation that in all actions of consequence in Court, a woman is not only always an ingredient, but commonly a principal drug of most virtue,” he noted, “and she shows that they are not incapable of conducting business, nor her self void of wit and subtlety.” It’s not hard to imagine why tales were spun around Jahangir’s early infatuation with Nur, since the days he was Prince Salim. Some chroniclers even claim that young Mihr was married off to a fellow Persian nobleman, Ali Quli, to keep her away from the smitten crown prince.

Yet it would be patently unfair to reduce Nur’s influence to her “womanly wiles”. As an astute observer of court politics, she played her hand shrewdly. Initially, she forged an alliance with the ambitious Prince Khurram (later Shah Jahan), but then Nur got her only daughter, Ladli Begum (by her first husband), married to the younger Prince Shahryar, hoping to push the latter for the throne. With Jahangir’s health worsening due to his addiction to alcohol and opium and civil wars breaking out between factions of the royal family, Nur became increasingly anxious about her hold over the palace. The last straw was the ascension of Shah Jahan to the throne after Jahangir’s death when he stripped Nur of her privileges. She was packed off to live on a modest pension away from the court. In exile, too, she conducted herself with the dignity and grace suited to her station as a noblewoman. Known for her philanthropic work for the poor, she also built a tomb for her parents in Agra that would become the model for the Taj Mahal.

Nur Jahan was neither a Machiavellian dissenter nor a feminist rebel, as Lal writes tellingly. She seemed to have accepted the “emphatically patriarchal” norms of her time, the rules of the feudal, aristocratic world she spent her life in. “I do not believe feminist history should be one in which the woman is always a winner,” says Lal. “It is (rather) what she does, and how effectively she does it, despite all odds. Vulnerability is feminist history.”

source: http://www.livemint.com / Live Mint / Home> Lounge> Leisure / by Somak Ghoshal / August 31st, 2018