INDIA:

Traders from the Middle East introduced the beverage to the Mughal empire but the British made tea the subcontinent’s preferred drink.

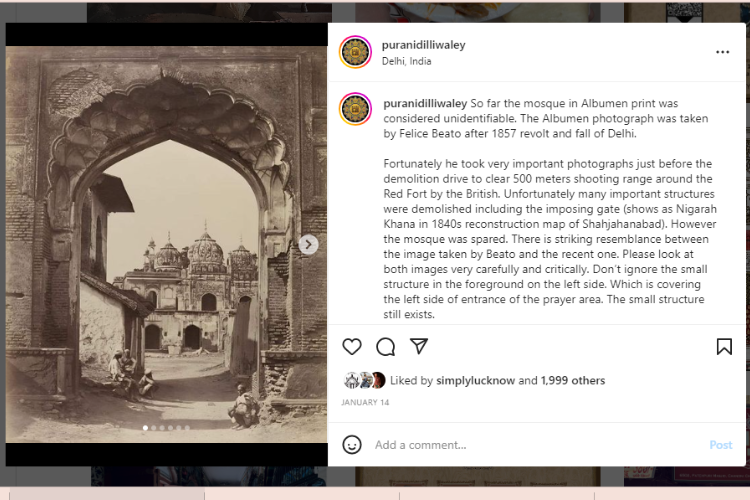

The sun sets behind regal yet dilapidated Mughal mansions and the magnificent dome of the Jama Masjid as the call for the evening prayer fills the auburn sky in Old Delhi.

Chandni Chowk’s bustling streets reverberate with the sound of honking cycle rickshaws navigating the serpentine lanes.

The sunset marks the beginning of business hours in the neighbourhood, which emerged during Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s rule; a pocket within the once spectacular walled city of Shahjahanabad, founded in 1648.

Immersed in the soundscape, one’s senses are drawn to the aroma of food being prepared, complemented by the unmistakable scent of masala chai – the Indianversion of spiced tea.

Tea stalls, resembling busy beehives, draw Delhiites patiently waiting for their daily dose of evening tea – some having travelled from the far ends of the city to satisfy their craving.

Tea is without a doubt a national obsession in India. However, the incredible popularity of the drink in the subcontinent is less than two centuries old and only came about as a result of British rule in the region.

It may come as a surprise, but before the arrival of the British, it was coffee that Indians preferred.

Sufis and merchants

Coffee was brought over from the Horn of Africa to Yemenat some point in the 15th century and later spread north into the Near East and then to Europe by the 16th century.

The beverage also spread eastwards, and India’s Mughal elite was quick to adopt it as their beverage of choice.

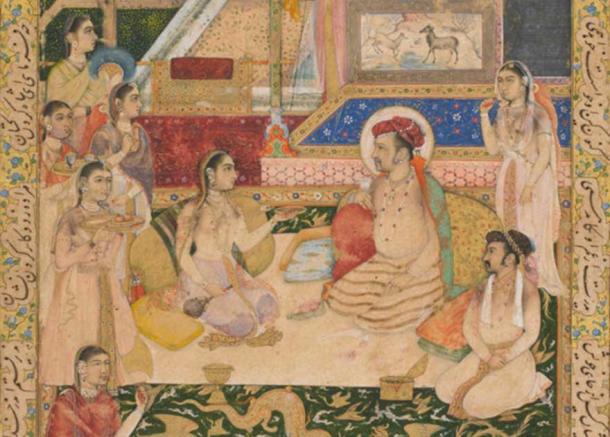

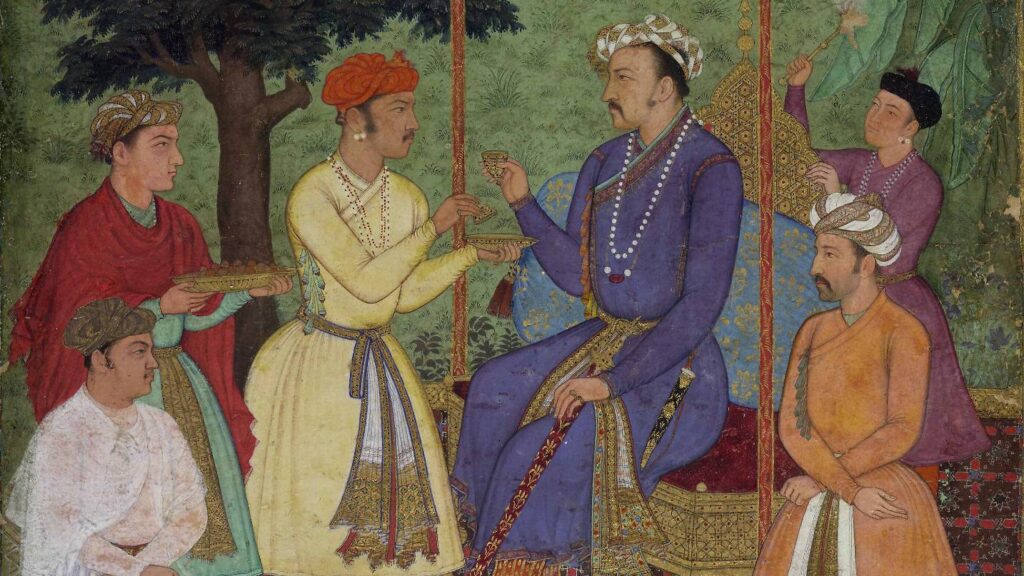

While the Mughal Emperor Jahangir had a penchant for wine – preferring the Shiraz variety – both Hindu and Muslim nobility in his court freely indulged in coffee.

Edward Terry, a chaplain with the English embassy at Jahangir’s court, mentions that members of the court were captivated by the then-novel qualities of coffee, believing it could “invigorate the spirits, aid digestion, and purify the blood”.

The coffee bean was brought to the subcontinent by Arab and Turkic traders who had strong trade ties with the Mughal Empire.

They not only brought coffee, but also other items, including silk, tobacco, cotton, spices, gemstones, and more from the Middle East, Central Asia, Persia, and Turkey.

Such goods would reach the farthest corners of India, including the easternmost region of Bengal. By the time Jahangir’s son, Shah Jahan, ascended to the throne (1628-1658), interest in coffee had spread across society.

Coffee was considered a healthy drink, an indicator of social mobility, and an integral part of Delhi’s elite social life.

Like Terry, another contemporary European visitor, the German adventurer Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo, wroteabout his travels in the east through Persia and Indian cities, such as Surat, Ahmedabad, Agra, and Lahore in a memoir titled The Voyages and Travels of J Albert de Mandelslo.

In 1638, Mandelslo describes kahwa (coffee) being drunk to counter the heat and keep oneself cool.

In his workTravels in The Mogul Empire (1656-1668), Francois Bernier, a French physician, also refers to the large amount of coffee imported from Turkey.

Besides its use in social settings and supposed effects to ward off heat, the drink also had a religious purpose for the subcontinent’s ascetics.

Like their brethren in the Middle East and Central Asia, India’s Sufis consumed coffee before their night-long reverential rituals known as dhikr (the remembrance of God).

Legend has it that a revered Sufi saint named Baba Budhan carried back seven coffee beans in the folds of his robe on his way back from Mecca in 1670, planting the seeds for Indian-origin coffee cultivation in a place called Chikmagalur.

While this story may or may not be true, today the Baba Budhangiri hill and mountain range in the Indian state of Karnataka bears his name and remains a significant centre for coffee production, as well as housing a shrine dedicated to the Sufi saint.

In another variation of the legend, shared by the government’s Indian Coffee Board, the Sufi saint travels to Mochain Yemen and manages to smuggle out the beans discreetly despite strict laws on their export.

Culture of consumption

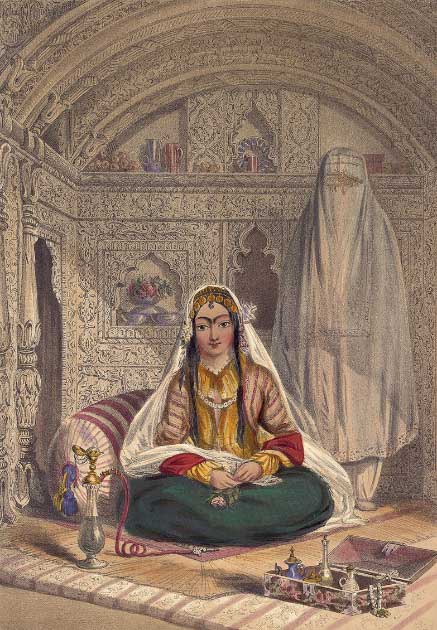

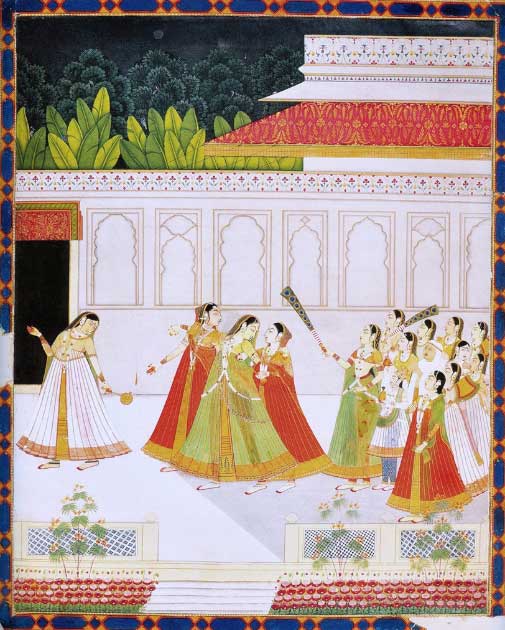

From the 16th century onwards, India became host to a cafe culture influenced by the one emerging in the Islamic empires to the west, particularly cities such as Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, and Istanbul.

The nascent coffee culture found expression in Shahjahanabad’s own “qahwakhanas”, or coffee houses.

In her essay Spilling the Beans: The Islamic History of Coffee, food historian Neha Vermani describes the coffee served at the Arab Serai, which was “famous for preparing sticky sweet coffee”.

The Serai, which was commissioned in 1560 by Hamida Banu, the wife of Mughal Emperor Humayun, still stands today as part of a Unesco heritage site ; the wider complex of Humayun’s tomb.

Historians say it was used as an inn by Arab religious scholars who accompanied the royal on her pilgrimage to Mecca and that it was also used to house craftsmen from the Middle East who were working for the Mughals.

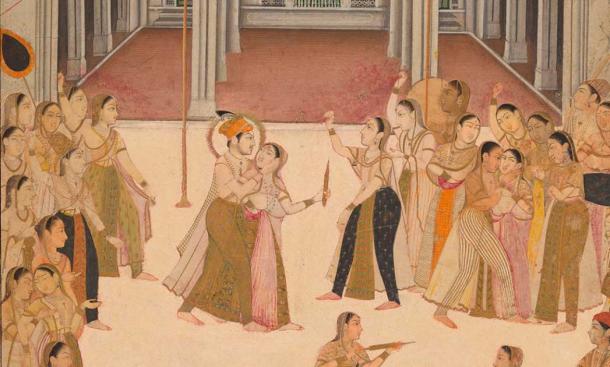

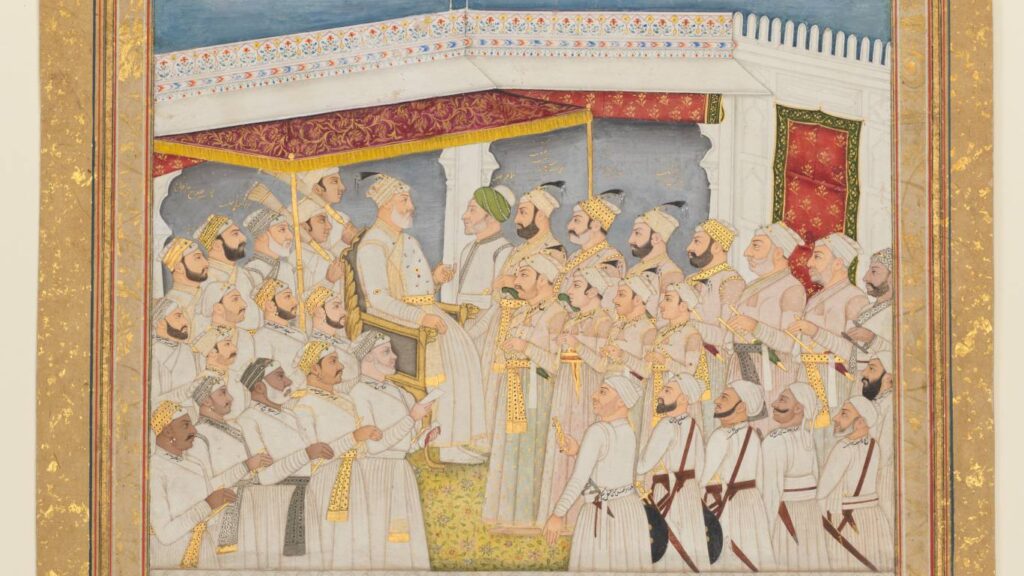

Historian Stephen Blake in his 1991 workShahjhanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India 1639-1739 describes coffee houses as places where poets, storytellers, orators, and those “invigorated by their spirits” congregated.

Blake described how vibrant these coffee houses were, their milieu of poetry recitals, storytelling and debates, long hours of playing board games, and how these activities impacted the cultural life of the walled city.

Coffee houses of Shahjhanabad, like those of Isfahan and Istanbul, accelerated the rise of a culture of consumption and a thriving food culture, with residents frequenting snack sellers offering savouries, naanwais baking bread, and halwais specialising in confectionery.

This is a legacy that continues to be felt in Old Delhi’s Shahjahanabad area to this day.

While Blake’s descriptions paint a picture, there are no extant visual depictions of the interiors of these establishments, and unlike their Ottoman or Safavid counterparts, there are no miniatures or Orientalist artworks depicting what they would have looked like.

Rembrandt depictedMughal men drinking something very closely resembling coffee but the Dutch artist does not identify the contents of their cup, and never visited India. But his images were inspired by Mughal paintings brought over to the Netherlands by Dutch traders.

The man who swore by his Turkish coffee

Provincial courts sought to replicate the ambience of Shahjahanabad and embraced the cafe culture on offer there. Among them, none cherished coffee more than Alivardi Khan, the Nawab Nazim of Bengal.

Khan was of Arab and Turkman descent and ruled Bengal from 1740-1756. Known as a diligent ruler, coffee and food were the two biggest pleasures of his life.

Seir Mutaqherin or the Review of Modern Times, written by one of the prominent historians of the time, Syed Gholam Hussein Khan, offers a fascinating description of Alivardi Khan’s routine.

He writes: “He always rose two hours before daylight; and after having gone through evacuations and ablutions, he performed some devotions of supererogation and at daybreak, he said his prayers of divine precepts, and then drank coffee with choice friends.

“After that he amused himself with a full hour of conversation, hearing verses, reading poetry or listening to some pleasing story.”

This morning routine was followed by a bespoke Persian dish prepared by the nawab’s personal chef.

Khan’s portrayal presents Nawab as a man of fine taste, who valued the luxuries of courtly life as much as effective governance.

A connoisseur of exquisite food, witty conversations, and premium Turkish coffee, Khan went to great lengths to acquire the best coffee beans, importing them from the Ottoman Empire and bringing them all the way to Murshidabad, his capital.

He believed in nothing but the best for his court. Not only were his coffee beans imported, but his kitchen staff also hailed from places renowned for their culinary excellence, such as Persia, Turkey, and Central Asia.

The royal household employed a diverse range of professionals, including storytellers, painters, coffee makers, ice makers, and hakims (physicians).

Khan personally handpicked his baristas (qahwachi-bashi), who brought along their specialised coffee-making equipment.

The descriptions paint a vivid picture of courtly culture, a world of opulence, artistry, and a profound affinity with caffeine.

It is puzzling, therefore, to pinpoint exactly when Mughal coffee culture vanished from pre-colonial Bengal, but it likely lasted until at least 1757.

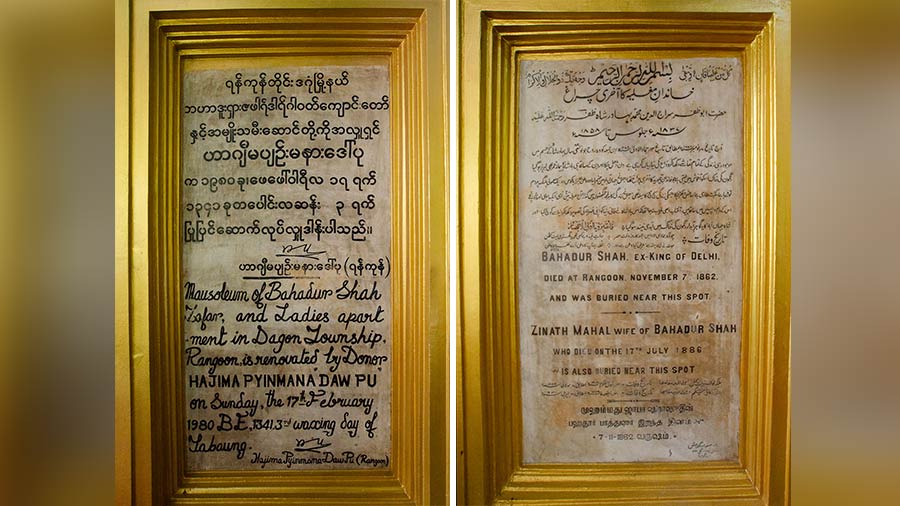

Siraj ud-Daulah, Khan’s grandson and successor, could not live up to his grandfather’s legacy, and faced with threats from the British, the courtly culture swiftly dissipated, along with Bengal’s fortunes.

When Bengal lost the decisive Battle of Plassey in 1757, the East India Company took control of the region, and slowly coffee vanished from public consumption and consciousness.

Tea farming takes over

The rise of the East India Company, which was the primary agent of British control in India, marked the end of the subcontinent’s dominant coffee culture.

Britain’s penchant for tea began in the late 17th century and China was its main supplier.

Lizzy Collingham writesin her book Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors that between 1811 and 1819 “70,426,244 pounds” out of a total of “72,168,541” pounds of imports from China were associated with the tea trade.

She remarks that Britain, therefore, had an “interest in finding an alternative source for tea”.

With its fertile soils and appropriate weather conditions, India was the perfect spot.

In February of 1834, then Governor General William Bentick appointed a committee to look into India’s potential as a place to set up the East India Company’s own tea production unit.

In the native Indian population, they found not only workers who would cultivate and harvest the leaves but also consumers of the beverage.

As coffee production became overshadowed by tea farming, Indian tastes also shifted to the latter.

Further consolidating the decline of Indian cafe culture was the British ban on Indians visiting coffee houses, which were barred to all but Europeans.

Nevertheless, reports of the death of coffee in India were premature.

Regardless of British influence on local culture, the subcontinent was not immune to global trends.

The Indian historian and author, AR Venkatachalapthy, writes in his 2006 book In Those Days There was No Coffee: Writings in Cultural History that there was no escaping the physical effects or symbolism of coffee in late 19th century British India.

“Drinking coffee, it appears, was no simple quotidian affair. Much like history, the nation-state, or even the novel, coffee too was the sign of the modern,” he writes.

Enthusiasm for coffee grew at the turn of the 20th century, and the same book quotes adverts for coffee in south India in the 1890s: “Coffee is the elixir that drives away weariness. Coffee gives vigour and energy.”

This energy and vigour were first reflected in the east, in the colonial city of Calcutta (present-day Kolkata) where the first Indian-run coffee shop, named Indian Coffee House, opened in 1876.

pix09

Turning into a chain in the 1890s, by the first half of the new century the name Indian Coffee House would be adopted by a growing network of 400 coffee houses run by Indian workers’ cooperatives, with only Indian-origin coffee.

These were the people’s coffee houses where any Indian could walk in without being discriminated against on the basis of their race.

Today, the ambience of the Indian Coffee House reminds one of the inclusivity of coffee shops in historic Shahjhanabad.

The chain is one of many Indians can visit, with others including the Bengaluru-based Coffee Day Global, which now has more than 500 outlets in the country despite only opening its first in 1996.

Six years later Starbucks entered India’s voluminous urban market and the rules of the brew changed forever in the subcontinent.

source: http://www.middleeasteye.com / Middle East Eye / Home> Discover> Food & Drink / by Nilosree Biswas, New Delhi / June 05th, 2023