Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA / Aligarh, UTTAR PRADESH :

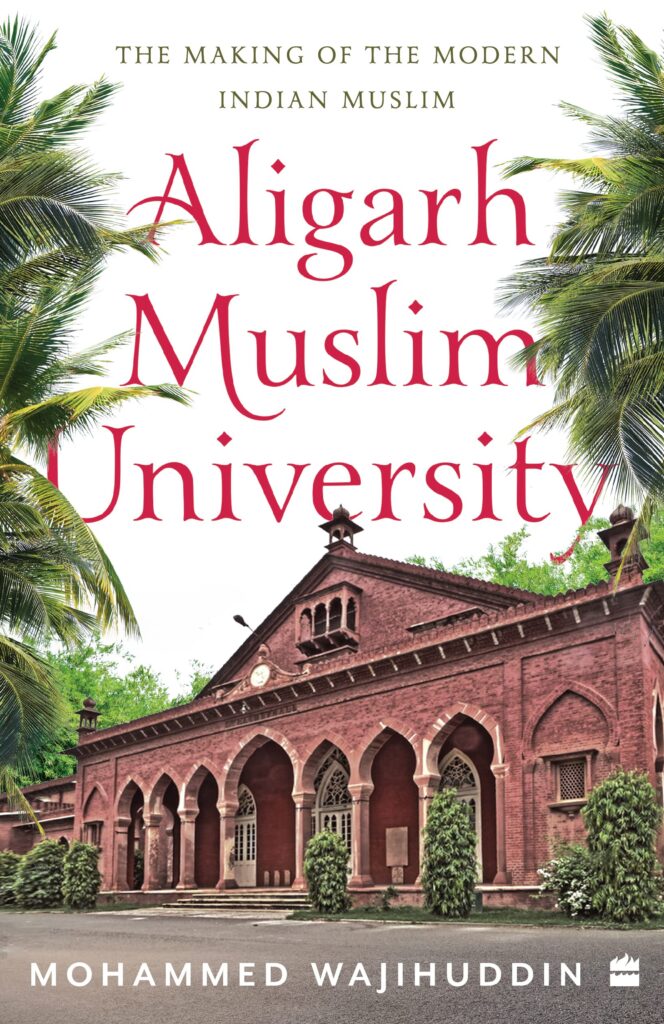

- The book “Aligarh Muslim University: The Making of the Modern Indian Muslim” by Mohammed Wajihuddin sheds light on AMU and its role in determining where the Muslim community stands in modern-day India.

- The Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) completed a hundred years in December 2020. In December 1920, the Mohammedan Anglo Oriental (MAO) College founded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in 1877, was transformed into AMU. Sir Syed also established the All India Mohammedan Educational Conference to infuse the subcontinent’s Muslims with a spirit of modernism. This helped prepare the community, devastated in the aftermath of the Revolt of 1857, for new challenges.

- Zakir Hussain, AMU alumnus, its former Vice-Chancellor and a former President of India, said over fifty years ago, ‘The way Aligarh participates in various walks of national life will determine the place of Muslims in India’s national life. The way India conducts itself towards Aligarh will determine largely, the form which our national life will acquire in the future.’

- Read an excerpt from the book below.

With AMU turning a hundred, one is beholden to the MAO College Fund Committee’s first meeting on 10 February 1873. The fund committee was formed a year earlier, in 1872. Addressing the meeting, Syed Ahmad Khan’s son Syed Mahmood (1850–1903), had said: ‘I think what we mean to found is not a College but a university, and I hope the members will consent to my proposal that instead of the word “College”, the word “University” may be substituted.’

Since the formal opening of MAO College was getting delayed, the fund committee began a school called Madrasatul Uloom Musalmanan-e-Hind on 24 May 1875 at Aligarh. The school was a precursor to MAO College, which metamorphosed into AMU in 1920, and during whose foundation-stone-laying ceremony on 8 January 1877, presided over by Viceroy of India Lord Lytton, Sir Syed had observed:

… this is the first time in the history of Muhammedans of India that a college owes its establishment not to the charity or love of learning of an individual nor to the splendid patronage of a monarch, but to the combined wishes and the united efforts of a whole community. It has its origin in causes which the history of this country has never witnessed before.

So, what were the causes Sir Syed alluded to?

The large-scale killings and destruction in the wake of the failed 1857 Mutiny had unsettled Sir Syed, a judicial official in the East India Company. Muslims, who had borne the brunt of British repression heavily because the British held them responsible for the rebellion, had become fatalists. Irrationality, an obsession with obsolete and redundant social mores, rigidity in religious practices and a refusal to adapt to the new realities made them misfits in the era that the British Raj heralded. On close scrutiny, Sir Syed found that the reasons for the Muslims’ unfathomable desolation lay mainly in their educational backwardness and resistance to modern, scientific thinking. Therefore, he saw a panacea for the community in modern, scientific learning. He began thinking about ways and means to bring his community out of the stupendous self-pity it wallowed in.

A visit to England in 1869 enabled Sir Syed to see first-hand the education system of the West, including that at Oxford and Cambridge. With the dream of an Indian college modelled on Oxbridge before his eyes, he returned to India and set out to realize that cherished dream. He quit his job in Benares and made Aligarh, then a small mofussil town 100 miles off Delhi on the Delhi–Calcutta route, his home. Since Sir Syed had saved several family members, including women and children, of some senior British officials during the 1857 Mutiny from Indian rebels and was among the defenders of British rule in India, no roadblocks in his path to founding his college remained permanent.

In Aligarh, he set up a residential college which would become the heartbeat of Muslims, as well as of a large swathe of undivided India. Alongside the college project, Sir Syed began the herculean task of social and religious reform. For this he established the Tahzibul Akhlaq or Mohammedan Social Reformer, a magazine in Urdu, which began hitting at the obscurantist, obsolete views that fettered the community. Other magazines were specially published to counter the views spread by the Tahzibul Akhlaq. Some of Sir Syed’s religious views were unpalatable to the ulema and against accepted Islamic beliefs, and earned him the wrath of the orthodox elements in the community. He had to face the fury of fatwas. A maulvi even went all the way to Mecca to fetch a fatwa of kufr, declaring him an infidel. Sir Syed only chuckled at the serious drive to declare him a heretic, kafir or infidel, as it gave some of his tormentors an opportunity to visit Islam’s holiest places. Sir Syed’s debt to India in general and Muslims in particular lies not just in the college that he established but in the overall impact he left on the lives of Indians, especially Muslims.

Over 123 years after his death, Sir Syed is not considered a heretic, a naturi (one who propagated the belief that Islam is compatible with nature), a British stooge—epithets that some of his own community members hurled at him in his lifetime. Today, the orthodox ulema publicly say that Sir Syed, like any other person, is merely accountable to God for his lapses, and that his achievements and noble works outweigh his shortcomings and will pave his way to paradise.

Tomes have been penned on Sir Syed, MAO College, AMU and the movement Sir Syed and his associates like Mohsinul Mulk, Viqarul Mulk, Maulana Shibli Nomani, Maulana Zakaullah, Altaf Hussain Hali, Nazir Ahmad, and Chiragh Ali launched. This was called the Aligarh Movement, and it can only be described as the trigger for the Muslim renaissance in the subcontinent in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is easy to do a panegyric while evaluating the 100-year-long journey of a university which was born in the tumultuous times of India’s freedom struggle of the 1920s.

The circumstances in which Jamia Millia Islamia came up deserve some detailing. In 1920, Mahatma Gandhi gave a call for the boycott of government and government-aided schools and colleges. Muhammad Ali opposed MAO College as it was pro-government, since it received government grants. Gandhi, Muhammad Ali and Shaukat Ali tried to persuade the pro-government elements at Aligarh to join the nationalist movement and turn the college into a nationalist institution. The pro-government group at Aligarh opposed the presence of Gandhiji and the Ali brothers at the campus as they were trying to persuade students to join their movement. On 12 October 1920, Mahatma Gandhi addressed the students and left. But the real drama happened on 13 October, when the Ali brothers suddenly appeared at a meeting being held at the students’ union. Since they had been witness to Gandhiji being hooted and booed the previous day, the Ali brothers didn’t speak but said they had only come only to say goodbye to the students of their alma mater. And they wept too because they had seen Gandhiji being booed. Present there was also Zakir Hussain, who had done his MA in economics from AMU and was a part-time teacher at the university. Zakir Hussain had arrived from Delhi the same day; he was running a fever and didn’t want to speak. But he couldn’t hold back his own tears when he saw the Ali brothers weeping. He stood up and declared that he had decided to resign from his teaching assignment at MAO College and forego the scholarship being given to him. This tilted the balance and changed the mood. Many students joined him in boycotting government institutions. In his biography Dr Zakir Hussain, M. Mujeeb, a colleague and friend of the professor, says that Hussain went to Delhi, where he met Dr M.A. Ansari, Hakim Ajmal Khan, Muhammad Ali and many others and ‘assured them that a large number of teachers and students would leave the MAO College to join a national institution, if one was established. The leaders could ask for nothing better. On 29 October 1920, the Jamia Millia Islamia came into existence, and Maulana Mahmudul Hasan of Deoband delivered an address indicating its aims and ideals.’

Excerpted with permission from Aligarh Muslim University: The Making of the Modern Indian Muslim, Mohammed Wajihuddin, HarperCollins India. Read more about the book here and buy it here.

source: http://www.thedispatch.in / The Dispatch / Home> Book House / by Mohammed Wajihuddin / January 25th, 2022