Surendranagar / Vadodara, GUJARAT :

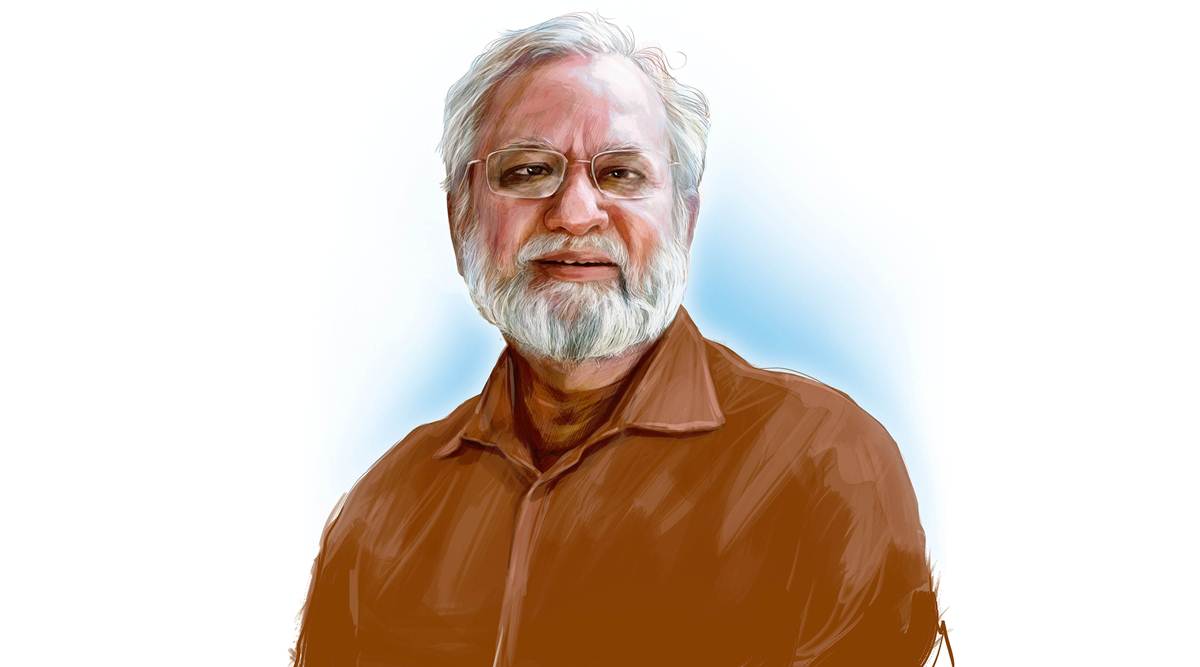

Gulammohammed Sheikh: ‘What we need is an open climate within our institutions to allow artists to practise their art’

Gulammohammed Sheikh speaks on the idea of multiplicity in life, art education in India, interference in institutions and how the world of art remains free of divides. This session was moderated by Vandana Kalra, Senior Assistant Editor, The Indian Express .

Vandana Kalra: In 1981, you had said that living in India means living simultaneously in several times and cultures. Do you think the relevance of your statement has only increased over time? Also, how do you look at the works that you made during that period, for example, City for Sale?

Among these works, the first one was About Waiting and Wandering, the other was Speaking Street, the third Revolving Routes and the fourth City for Sale. They relate to actual situations and are connected.

Speaking Street was a re-creation of the kind of street that I lived in during my childhood. Born in 1937, I spent about 18 years in Surendranagar, which was then a small town, before I came to Baroda to study. We lived in a little lane, which had a little mosque whose walls were painted green with enamel colours, but it didn’t have a dome. There would be people sitting on the street selling fish, or somebody pulling a little cart. In the lower half of the painting there are several events taking place simultaneously in different houses or rooms, as would happen with people living in chawls. Speaking Street also carries a personal portrait — a young boy looking out of a window. Thinking of the childhood spent in a street like that, I remember having learnt to recite the Quran in Arabic at a madarsa, while studying Sanskrit at school. It gave me the idea of multiplicity in life, connected by multiple belief systems.

This work connects with the much larger City for Sale, based in the city in which I continue to live; the city of Baroda, now Vadodara. I came to Baroda first in 1955 as a student, and after finishing my studies at the Faculty of Fine Arts, I taught there for three years. I was then in London on a scholarship for three years and returned home in 1966. When I first came to Baroda, it opened for me not just the world of art, but also the art of the world. But in 1969 this city produced another image. Some of the worst communal riots took place here between 1969 and 1970. People began to look at me with my name in mind. So, it gave me an identity which was different from the identity that I had acquired when I had reached Baroda, then — open, liberal, multifaceted. In 1969, suddenly the situation changed. These four paintings, in some ways, reflect upon the times that I had gone through. City for Sale is large and has multiple figures, so many characters. There are three men meeting on the pretext of lighting a matchstick. Would that provoke incendiary connotations? There is also a woman who has a big vegetable cart, which literally flows into the town. Then there is, in the centre, a film being shown called Silsila (1981). And on the top, the scene of a communal riot. It brought together multiple parts of a city, depicting how riots are raging in one part, but a film is being shown in another. In a way, it was confessional, it was also some kind of a release for me.

Yes, there are problems that beset our institutions. Government museums and academies are out of touch with what’s going on in the world of art, and directors are often appointed rather arbitrarily, often not from the art world at all

Vandana Kalra: In more recent years, you’ve taken this thought forward and you seem to have turned to Kabir and Mahatma Gandhi to call for peace, call for intermingling. If you could talk a bit about that.

Gandhi came to me right from the time I was in school. I read My Experiments with Truth (1927), in Gujarati it’s Satya Na Prayogo. It has remained with me ever since. During the years of 1969 and 1970, Gandhi kept coming to me, in different forms, different guises. But I didn’t know how to paint Gandhiji, I had never seen him in person. I saw lots of photographs. Then I devised something. The first painting that I made of him was of Gandhi in South Africa, in the image of a young lawyer. But the second one, which I have used twice or thrice since, was the image of Gandhi returning to India, quoted from a painting by Abanindranath Tagore.

Kabir came in a different way. I was familiar with his poetry from my school days but he began to become more and more relevant in the context of the conflicting situations that I saw around myself. I thought, perhaps, I should try to paint Kabir. But how to paint Kabir? My mentor KG Subramanyan’s mentor Benodebehari Mukherjee had painted a large mural in Santiniketan on the saint-poets of India, which included Kabir. Benode babu knew that Kabir was a weaver, so he went to the weavers’ colony to search for his image of a weaver and made his Kabir. I found a Kabir image in a late Mughal painting in the British Museum collection and devised a Kabir-like persona from that image. As Kabir began to recur in my mind, I began to read Kabir but it was difficult to find a visual equivalent. It was when I heard Kumar Gandharva singing Kabir that I thought, why can I not illustrate his poetry? Within histories of art, a great number of paintings illustrate poetry.

We have to think of a holistic way of devising a new art education system for our country. An art education system that is not standardised. It should leave room for each region, each culture in a diverse country like ours

Vandana Kalra: How do you look at the dialogue between your poetry and painting?

When I started writing poetry while I was in school, it was very traditional, using Sanskrit meters or in the form of songs. When I came to Baroda, I met a new mentor, Suresh Joshi, the writer who pioneered a modern idiom in Gujarati. He introduced us to Baudelaire, Rilke, Lorca, etc. After reading these great poets, I felt what I was writing was not worthwhile, so I threw away much of it, and began to write poetry without verse, without any meter. I felt I should use spoken language. I had to find my voice from within the spoken word. In some ways, I had to find something which was not only modern but also personal, which was mine. Similarly, in painting, I had to struggle hard. Every student feels that he is under the shadow of his teacher, so he wants to get out of that shadow. I started to look outside of Baroda. I looked at MF Husain and began using the image of a horse. But there was a difference between Husain’s horses and mine. Husain’s horses are to be regarded as timeless. Charged with energy, they were larger than life. My lonely creature came from my life experiences, perhaps it came from the tonga, the ghoda-gaadi that I knew from my childhood. This horse was harnessed and was trying to unshackle itself.

” The world of art in India is still free of divides… For us it was a mini India, a multiple India; it was not straitjacketed into the singular. Many of us found our life partners from within the Faculty we taught and studied at

Devyani Onial: What do you think about art education in India? Also, you started teaching when you were very young. Can you talk a bit about those days?

Art education should begin at school and children should be taken to art galleries and museums. I’ve seen not just in the West, but also in places like Indonesia, tiny tots are taken to museums, they have their little notebooks with them in which they write about the paintings that they see.

The Faculty of Fine Arts (MS University), set up around 1950, was the first institution in India where university education included fine arts. It offered not a diploma, but a degree.

What the pioneers visualised was an artist who was literate and educated, a new citizen of modern India, because it coincided with the independence of the country. It was a small institution, the teacher student ratio was one to 10, or one to 15. The studios were huge, they were like warehouses and were open throughout the day and night. For somebody like me, coming from a small town, it was a great experience to learn from your teachers who were working alongside you. We saw NS Bendre working, we saw our seniors like Jyoti Bhatt, Shanti Dave and GR Santosh working. Despite the fact that I had some financial difficulties, I managed to sail through those four years of under-graduation, and then even did my master’s. I got a job to teach while I was in my second-year master’s course and some of my classmates also became my students for a brief while. But art education, even to this day, is a neglected discipline. We have to think of a holistic way of devising a new art education system for our country. An art education system that is not standardised. It should leave room for each region, each culture in a diverse and multifarious country like ours.

Leena Misra: Vadodara was recently in the news because Chandra Mohan was not allowed to display his artwork. It was also in the news because they have booked the first case of interfaith marriage, which violates the freedom of religion. So what do you think went wrong in the city and why are people not speaking up? Has the space for expression, even for artists, shrunk?

It’s not that people were not speaking. Prof Shivaji Panikkar, the then in-charge Dean of the Faculty, stood firm defending the student against a controversy engineered by external elements. A spate of protests by students against the assault on the institution continued for almost a year. Several of us spoke. Ganesh Devy (literary critic) had also spoken up. But the issue that you’re talking about is larger. What we need is an open climate within our institutions of art and art education, to allow artists to practise their art. External issues have been brought to institutions, which then have been victims of unhealthy controversies and conflicts. I think artists should and would articulate their ideas through their art and there are artists who have done that. I will quote the German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht: “Will there be singing in the dark times?” To which the answer is, “Yes, there will be singing about the dark times”.

External interferences are mostly politically motivated, we got to stand against them but while continuing to practise. If you stop practising, if you do not paint, that is more dangerous. Baroda had a liberal foundation and to an extent it still exists. The world of art and artists in India is still free of divides. Let me give you example of five of my teachers from the Faculty of Fine Arts. The first dean Markand Bhatt, a Gujarati, was married to Perin, a Parsi. NS Bendre, a Maharashtrian, married Mona, a Tamilian. Sankho Chaudhuri, a Bengali, married a Parsi fellow artist Ira, and K G Subramanyan married Sushila, a Punjabi, the last two couples had met in Santiniketan. For us it was a mini India, a multiple India; it was not straitjacketed into the singular. Many of us found our life partners from within the Faculty we taught and studied at. A Kashmiri Ratan Parimoo found Naina, a Gujarati; a Maharashtrian PD Dhumal, married Rini, who was a Bengali. So there was nothing unusual in a Gujarati like me marrying a Punjabi Nilima. That has been the culture of the Faculty of Fine Arts. We lived a life which was not just a life lived, but a life shared.

Shiny Varghese: What do you think are the values that we should support today that will determine what our future will be like tomorrow?

I would answer your question in a different way. Frankly, my own view is that contemporary Indian art is still very vibrant. We have three to four generations of artists working. We have 97-year-old Krishen Khanna, of the generation of Husain. You have my generation, and you have those that come after us, like Atul Dodiya, Sudarshan Shetty and several others. Then there is a still younger generation working. I’m not painting a rosy picture. What I am trying to say is that within art, among artists, there is still a dialogue, and they are working steadfastly. I’m also very happy that we have many women artists. We also have several couple-artists, doing different things in their own way. Like Manu and Madhvi Parekh, Arpita and Paramjit Singh, Reena and Jitish Kallat, Atul and Anju Dodiya, Bharti Kher and Subodh Gupta among others. I wonder if such a situation prevails in other countries. I am putting it in a somewhat simplistic manner but the values our artists seem to pursue are the values of a free and creative practice. Most of us are engaged in finding a visual language for contemporary issues, often referring to problematics of our times. Then, there are so many young artists. We have a young artist called BR Shailesh, who was trained in a gurukul, he speaks Sanskrit, he came to study painting, and he ventured into digital art, then into installation. He is using his gurukul background and devising a way where there is both critique as well as celebration.

Rinku Ghosh: On the one hand you say art is about hope, on the other you choose to stay away from rescuing institutions like the National Gallery of Modern Art and Lalit Kala Akademi from decay. How will young artists express themselves freely if greats like you don’t act?

It is not correct. Artists have always spoken out in one way or another. A long time back, in the 1960s, J Swaminathan published Contra (1966-67) to take on the Akademis, we (Bhupen Khakhar and I) brought out a journal called Vrishchik (1969-73) and through that, amongst other things, mounted a campaign to reform the Lalit Kala Akademi. We fought for three years, as a result of which the government appointed the Khosla Commission. Some of the reforms that we were fighting for were included. So, it’s not that artists have not driven change. Yes, there are problems that beset our institutions. Government museums and academies are out of touch with what’s going on in the wider world of art, and directors are often appointed rather arbitrarily, often not from the art world at all. Are we to become activists then? When KG Subramanyan was asked the question, he said tellingly that yes, he would, but as an artist activist, not as an activist artist. The younger generations of artists too have their own modes of articulating the need for change, their own activism.

Paromita Chakrabarti: Could you speak about the time when you met your wife? You mentioned how it was commonplace in the artistic community to find partners from other communities. In the larger city, for instance, was there the ghost of love jihad at that time, which has become so prominent now?

I have already made some remarks about the issues earlier. I have tried to answer these through the paintings that I have done, including City for Sale, which is about the city and which deals with the kind of conflicting situation you are talking about.

External interferences are mostly politically motivated, we got to stand against them but while continuing to practise. If you stop practising, if you do not paint, that is more dangerous. Baroda had a liberal foundation and to an extent it still exists. The world of art and artists in India is still free of divides. Let me give you example of five of my teachers from the Faculty of Fine Arts. The first dean Markand Bhatt, a Gujarati, was married to Perin, a Parsi. NS Bendre, a Maharashtrian, married Mona, a Tamilian. Sankho Chaudhuri, a Bengali, married a Parsi fellow artist Ira, and K G Subramanyan married Sushila, a Punjabi, the last two couples had met in Santiniketan. For us it was a mini India, a multiple India; it was not straitjacketed into the singular. Many of us found our life partners from within the Faculty we taught and studied at. A Kashmiri Ratan Parimoo found Naina, a Gujarati; a Maharashtrian PD Dhumal, married Rini, who was a Bengali. So there was nothing unusual in a Gujarati like me marrying a Punjabi Nilima. That has been the culture of the Faculty of Fine Arts. We lived a life which was not just a life lived, but a life shared.

Shiny Varghese: What do you think are the values that we should support today that will determine what our future will be like tomorrow?

I would answer your question in a different way. Frankly, my own view is that contemporary Indian art is still very vibrant. We have three to four generations of artists working. We have 97-year-old Krishen Khanna, of the generation of Husain. You have my generation, and you have those that come after us, like Atul Dodiya, Sudarshan Shetty and several others. Then there is a still younger generation working. I’m not painting a rosy picture. What I am trying to say is that within art, among artists, there is still a dialogue, and they are working steadfastly. I’m also very happy that we have many women artists. We also have several couple-artists, doing different things in their own way. Like Manu and Madhvi Parekh, Arpita and Paramjit Singh, Reena and Jitish Kallat, Atul and Anju Dodiya, Bharti Kher and Subodh Gupta among others. I wonder if such a situation prevails in other countries. I am putting it in a somewhat simplistic manner but the values our artists seem to pursue are the values of a free and creative practice. Most of us are engaged in finding a visual language for contemporary issues, often referring to problematics of our times. Then, there are so many young artists. We have a young artist called BR Shailesh, who was trained in a gurukul, he speaks Sanskrit, he came to study painting, and he ventured into digital art, then into installation. He is using his gurukul background and devising a way where there is both critique as well as celebration.

Rinku Ghosh: On the one hand you say art is about hope, on the other you choose to stay away from rescuing institutions like the National Gallery of Modern Art and Lalit Kala Akademi from decay. How will young artists express themselves freely if greats like you don’t act?

It is not correct. Artists have always spoken out in one way or another. A long time back, in the 1960s, J Swaminathan published Contra (1966-67) to take on the Akademis, we (Bhupen Khakhar and I) brought out a journal called Vrishchik (1969-73) and through that, amongst other things, mounted a campaign to reform the Lalit Kala Akademi. We fought for three years, as a result of which the government appointed the Khosla Commission. Some of the reforms that we were fighting for were included. So, it’s not that artists have not driven change. Yes, there are problems that beset our institutions. Government museums and academies are out of touch with what’s going on in the wider world of art, and directors are often appointed rather arbitrarily, often not from the art world at all. Are we to become activists then? When KG Subramanyan was asked the question, he said tellingly that yes, he would, but as an artist activist, not as an activist artist. The younger generations of artists too have their own modes of articulating the need for change, their own activism.

Paromita Chakrabarti: Could you speak about the time when you met your wife? You mentioned how it was commonplace in the artistic community to find partners from other communities. In the larger city, for instance, was there the ghost of love jihad at that time, which has become so prominent now?

I have already made some remarks about the issues earlier. I have tried to answer these through the paintings that I have done, including City for Sale, which is about the city and which deals with the kind of conflicting situation you are talking about.

It is difficult to tell you the personal story, but it was, and is not uncommon among artists to get acquainted with each other, and eventually to become not only friends but partners. The pursuit of our vocation brought us together. Several of my friends and students have married outside their communities. The kind of divide, that you belong to this belief system or you belong to that belief system, or that you come from Kerala or Bihar, is denounced in our community of artists. Art actually binds, art brings us together, art gives us a new world to live in. When I say that art spells hope, what I mean is that hope is the essence of the creative act. I still believe that a creative life also makes you a slightly better human being, because it allows you to keep the divide out, it allows you to share, it allows you to meet people, it allows you to connect with as many people as possible.

Suanshu Khurana: You mentioned Kumar Gandharva and the impact his Kabir bhajans had on your work. Are there any other musicians who’ve been a significant part of your consciousness while creating your art?

I listen to a lot of music. Even now, during the pandemic, we have a little bluetooth speaker and I listen to music every morning or while working. I listen to Mallikarjun Mansur, I love Bhimsen Joshi, I enjoy Kishori Amonkar’s singing. I have not known many musicians, but I had some connection with Kumar Gandharva because of the opportunities of meeting during the programmes at Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal during the 1980s, where I would listen to him. Among the series of Kabir paintings I made, two were companion pieces: a largish painting called Ek Achambha Dekha Re Bhai has the companion piece called Heerna. It is my tribute to Heerna sung by Kumar Gandharva.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Idea Exchange / by Premium, Express News Service / April 05th, 2022