Calcutta, INDIA / USA :

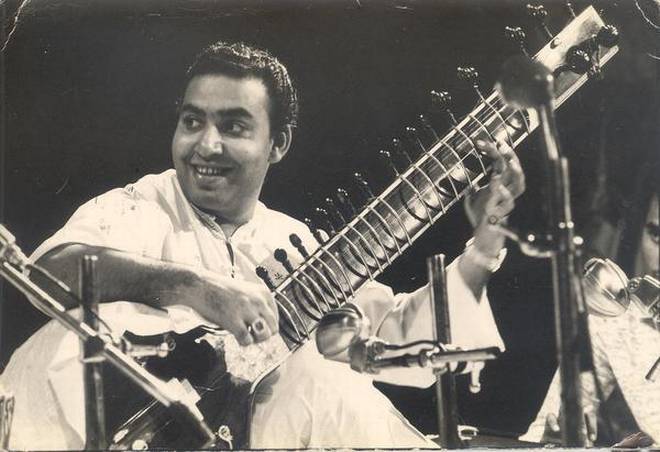

Remembering surbahar legend Ustad Imrat Khan, who shone bright despite being overshadowed by his celebrated brother Ustad Vilayat Khan

Mention the name Ustad Imrat Khan to any young Indian classical music lover, and chances are the reply will be, “Imrat Khan sahib? Oh yes, Ustad Vilayat Khan’s younger brother, the surbahar player.” But Ustad Imrat Khan was much more than just the younger brother of an iconic musician. He was also one of the finest instrumentalists of his time, an innovator, composer, great teacher, and the inheritor of the surbahar playing tradition of the five-generation-old Imdadkhani gharana.

Largely forgotten by a younger generation of listeners, he is a musician whose impact can be discerned in the instrumentalists of today. For one, the fact that he was as fine a sitar player as surbahar player was deliberately underplayed by his mother, Begum Inayat Khan, who was keen that the legacy of her late husband Ustad Inayat Khan be carried forward equally by both her sons, Vilayat and Imrat. From an early age, Imrat was encouraged to practise only the surbahar, on which he was trained by his uncle Ustad Wahid Khan.

Imrat was only three when his father died, so his gurus were his maternal grandfather, Ustad Bande Hasan Khan, uncle Ustad Wahid Khan, and brother Ustad Vilayat Khan. In the early years, the brothers were encouraged to also present their music as a jugalbandi, with Imrat playing the much heavier, more difficult surbahar with his brother Vilayat Khan on the sitar. Some of their immortal recordings, ‘Night at the Taj’, ‘Mian Malhar’, and a private recording of Yemeni on YouTube, reveal Imrat’s musical prowess. Although Ustad Vilayat Khan was famed for his amazing musicality, creativity and virtuosity, the jugalbandis reveal that Ustad Imrat Khan managed to hold his own with elan.

Looking at the legacy he left behind, foremost is his excellence as a guru. He was thorough, exacting, meticulous and inspirational. His sons and disciples, Nishat, Irshad and Wajahat, are well known worldwide. Ustad Imrat Khan was also a fine composer — Satyajit Ray, who interacted with him closely during the making of Jalsaghar, apparently said that though the name of the music composer was given as Ustad Vilayat Khan, it was Ustad Imrat Khan who dealt with the minute details. He created raags Chandra Kanhra, Madhuranjani, Geetanjali, Amrit Kauns, among others, but these never really became mainstream ragas.

Unusual raags, his forte

Understanding that he had to carve out a musical identity distinct from his more celebrated brother, Ustad Imrat Khan revelled in playing unusual raags; two that he popularised were Kalavati and Abhogi Kanhra. His compositions too reveal an attempt at individuality — son Ustad Nishat Khan speaks of a ‘gat’ in raag Gaoti, which was ‘the smallest gat ever composed, in which the mukhda was in just two matras. Says Nishat, “His compositions had a unique style; he used bolkaari (stroke work) in a distinctive way,” a style that was followed later by other instrumentalists. His son Ustad Irshad Khan remembers how he played compositions other than in teen taal. “This was something his gharana was not known for.”

The training on the surbahar gave him a command on the sitar that was awesome, and the wazan of his right hand, the fluid stroke work, and the extensive use of gamak taans on the sitar were distinctly his own. He preferred to encourage the then relatively lesser-known tabla players, Ustad Lateef Ahmed Khan of the Delhi gharana and Pt. Mahapurush Mishra and Pt. Kumar Bose of the Banaras gharana.

Yet, living in the times of those superb sitariyas, Ustad Vilayat Khan and Pt. Ravi Shankar, Ustad Imrat Khan never got the acclaim that was his rightful due. He moved to the U.K. where he taught at the Dartington College of the Arts, then to Europe in the mid-1970s, where he taught at the Central Academy of the Arts, Berlin, then moved to the U.S. in the 80s, where he taught at Washington University, St Louis. In the process, his concerts in India shrank, and a newer generation of listeners forgot his presence. Recipient of the Sangeet Natak award in 1988, the nation forgot him till his Padma Shri in 2017, which he declined as being too little too late.

The Ustad was a simple, large-hearted and fun-loving man. He loved good food and enjoyed watching Hindi movies. Most of his waking hours were spent in music, whether playing, listening or teaching. He was technically proficient, and and was able to tweak the jawari (the ivory tuning bridge) perfectly. A traditionalist, he turned down all offers for fusion concerts, saying there was enough to explore in Indian music. Today, four decades after his prime, one is able to appreciate the extent of his mastery.

The Delhi-based author writes on Hindustani music and musicians.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Entertainment> Music / by Shailaja Khanna / November 19th, 2020