KARNATAKA :

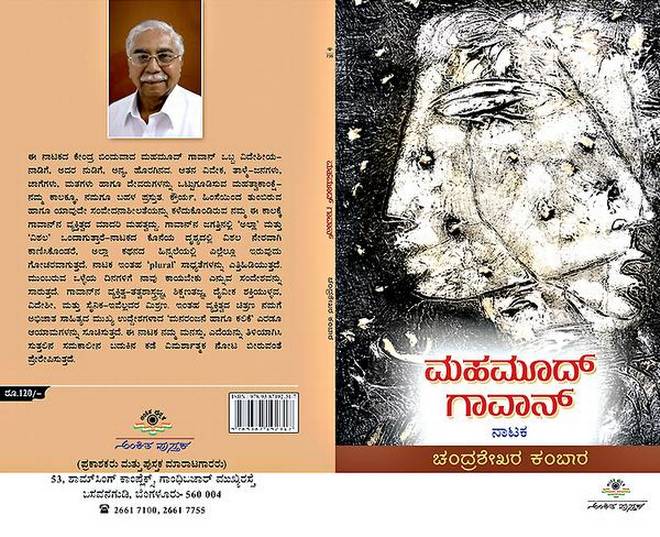

Chandrashekhar Kambar’s new historical play, Mahmoud Gawan, based on the life of the merchant who arrived in Bidar and later became the Prime Minister of the Bahmani Sultanate, will be released on Sunday

The word “global” is something that we come across not infrequently in literary discussions in recent times. It seems to be used in a very complimentary manner too. When we study it more closely, we see its multiple uses, ranging from the highly complimentary to the particularly disturbing connotations (especially, in the political and economic aspects of the so-called “globalization” phenomenon). Depending on the context, the philosophy implied in this use is vastly interesting.

In this context, dipping into pardonable autobiography, I must confess that my early acquaintance with the kind of writings I found in Chandrasekhar Kambar (this was back in 1964) was very new to my navya taste-buds of those days. This was around the time he wrote Helatini Kela . But, by the time Jokumaraswami arrived, I had begun to sense the fascinating spread of his literary intentions. The play seemed to insist on a message of passion (closely related to sexuality, the body, as well as the body politic!). The legitimacy of this passion was far more powerful than any petty legal correctness, or any mundane understanding of what constitutes the “moral” in our society. I was of course reminded of Lawrence. Kambar was utilizing passion as a powerful motive-free force, and constantly pushing at obstructions in its way. I became an avid follower of Kambar’s growth as a writer. His use of “sexuality” as a central and powerful theme and his struggle out of its grasp.

The latter part of his career witnesses an attempt to cover areas of creativity which could not be accommodated inside the constrictions of this strong force (note, however, a sliver of this sexuality is noticeable even in his latest play,Mahmoud Gawan ). I would assert that it is this constant and consistent presence which turns all of Kambar’s writing into his legitimate oeuvre.

Here was a writer, who, on the one hand was close to the North Karnataka folk and at the same time could engage the political and the modern predicament of our lives. You see this everywhere beginning from Helatini Kela , Rishyashringa , or Jokumaraswamy to the recent works like Shikharasoorya , Shivana Dangura orMahmoud Gawan . I would like to go back to what I began with, the idea of the “global” in relation to Kambar’s works. In what sense is Kambar global? It is true that at least in one of the recent novels globalisation and neo-colonialism figure predominantly (in Shivana Dangura ).

Could we try to identify an effort, more indirect, and subtler perhaps, to highlight an earlier moment in history, a moment that marked the international and inter-cultural ferment that characterised North Karnataka in his play, Mahmoud Gawan ? Interestingly, the choice of language in Gawan is not the kind of North Karnataka folk that Kambar worked with in say Helatini Kela or Jokumaraswami. I would describe the language of Gawan as Kambar’s idea of “neutral” Kannada, a conscious avoidance of the folk dialect. Again, look at the choice of the central figure in this play, Gawan. Hee is a foreigner, a non-Kannada person. He enters the world of Bahamani politics in the North Karnataka of fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. All these, I would venture to suggest, point towards a movement, a possibility, beyond the strictly local and Kannada contexts. In other words, Kambar is found testing his talent in handling something beyond what could be identified as exclusively Kannada, Karnataka. The significance of this kind of language use is for Kambar like playing a field without his arch-player—the folk tongue! Does he succeed in working this language, playing in this new field? Perhaps in a manner that is different from say Jokumaraswamy , where he is using sexual passion in order to design and project the drama experience, he is trying to move into other spaces in which his choice of an “other” Kannada could function adequately. This kind of language lends itself more easily to translation across other linguistic contexts. The absence of localism in itself is a strong pointer towards achieving such a global presence.

Could we simply say perhaps that Kambar moved from passion to politics—apparently, it seems so. This also begs the question, why? It is my opinion that an author like Kambar, a writer of immense literary imagination, constantly feels the need to move out of his familiar area of creativity and attempts to work in other new areas. As a result, politics becomes the main driving force in a play like Gawan . Overall, he succeeds in creating a layered experience of such historical and political play-fields. In Gawan , you see an extension of the literary Kambar, of Kambar’s entire literary oeuvre. And to say that is to acknowledge a serious happening in contemporary Kannada literature.

Finally, I invite my reader to look at Mahmoud Gawan, the protagonist. Here is a foreigner, theoretically foreign to the land and its language. His wisdom and his calming presence, his overarching ambition to unite people, places, religions, and gods—these are things crucially and painfully relevant to us and our times, times of cruelty and abhorrent insensitivity. In times where you see the cream of the population failing to respond to the degradation of all that is human, all that is noble and valuable in human experience.

In Gawan’s cosmos, Allah and Vitthala still fuse brilliantly—one as the implied presence and the latter as the explicit presence in the final scene. The play moves towards a certain sense of legitimization of this conclusion, the hope of better times to come. In a way, the encompassing presence of Gawan—the philosopher, educator, the saint, foreigner, and a soldier—should take us back to the classical idea of the function of literature, what literature should do—“to educate and entertain.” A closer look at the play would also perhaps clear our hearts and minds, making us look around at our own times with a sharply critical eye.

(Mahmoud Gawan by Chandrashekhar Kambar will be released on October 28 at 10. 30 a.m., Indian Institute of World Culture, B.P. Wadia Road, Bangalore).

(The author is a critic and musician of repute)

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> Friday Review / by Dr. Rajeev Taranth / October 26th, 2018