ASSAM / NEW DELHI :

Delhi-based poet Shalim M. Hussain’s Miyah poetry provides the metaphorical loudspeaker to the long-ignored voices of the Bengali-Muslim migrants living in the riverine plains of the Brahmaputra by documenting their stories of love, loss, celebration and injustice

Nana I have written attested countersigned

And been verified by a public notary

That I am a Miyah

Now see me rise

From flood waters

Float over landslides

March through sand and marsh and snakes

Break the earth’s will draw trenches with spades

Crawl through fields of rice and diarrhea and sugarcane

And a 10% literacy rate

See me shrug my shoulders curl my hair

Read two lines of poetry one formula of math

Read confusion when the bullies call me Bangladeshi

And tell my revolutionary heart

But I am a Miyah

See me hold by my side the Constitution

Point a finger to Delhi

Walk to my Parliament my Supreme Court my Connaught Place

And tell the MPs the esteemed judges and the lady selling

Trinkets and her charm on Janpath

Well I am Miyah.

Visit me in Kolkatta in Nagpur in the Seemapuri slums

See me suited in Silicon Valley suited at McDonalds

Enslaved in Beerwa bride-trafficked in Mewat

See the stains on my childhood

The gold medals on my PhD certificate

Then call me Salma call me Aman call me Abdul call me Bahaton Nessa

Or call me Gulam.

See me catch a plane get a Visa catch a bullet train

Catch a bullet

Catch your drift

Catch a rocket

Wear a lungi to space

And there where no one can hear you scream,

Thunder

I am Miyah

I am Proud.

Shalim Muktadir Hussain is not an easy man to get a hold of. He belongs to the long tradition of Bengali-Muslims who have been sharing their lived experiences through the genre of Miyah poetry. The genre originates from the Bengal Partition-era migrants residing in Lower Assam, locally known as Char-Chapori. With stories of love, loss, celebration and injustice, it has historically served to lift up the long-ignored voices of the Bengali-Muslim migrants living in the riverine plains of the Brahmaputra and document their interactions with the world outside the region. But Hussain’s activism isn’t limited to the written word – the first time that I’m able to get in touch with him, he is attempting to rescue his fellow Miyah poets, who have been arrested on account of their ‘divisive’ poetry. I try again, and this time, I catch him in the middle of helping the victims of a bus accident. This humanitarian spirit shines through in his poetry, which I was first acquainted with at Godrej Culture Lab’s Migration Museum, a one-day pop-up that shed light on partition-era struggles. Months later, he shares his views on the Miyah genre, the under-representation of Assamese voices, and more.

Tell us about your personal journey as a poet.

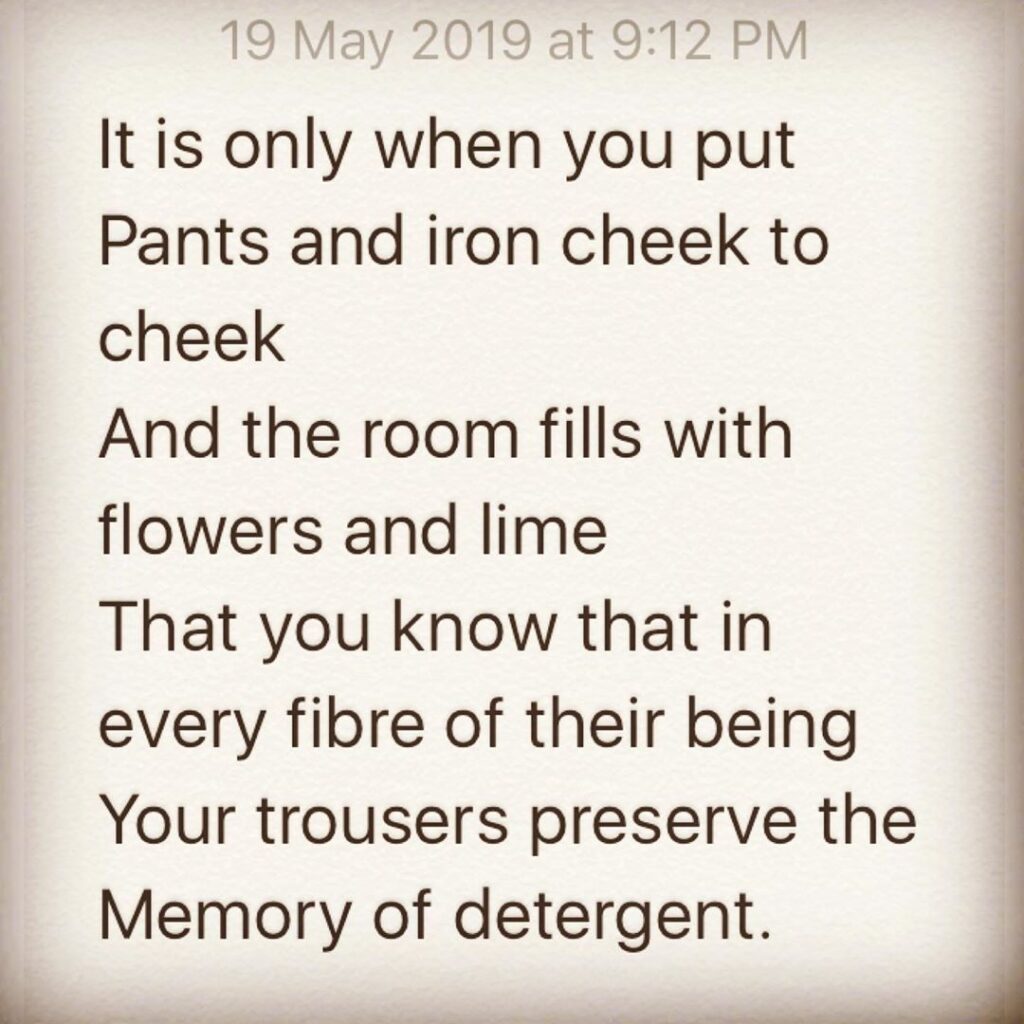

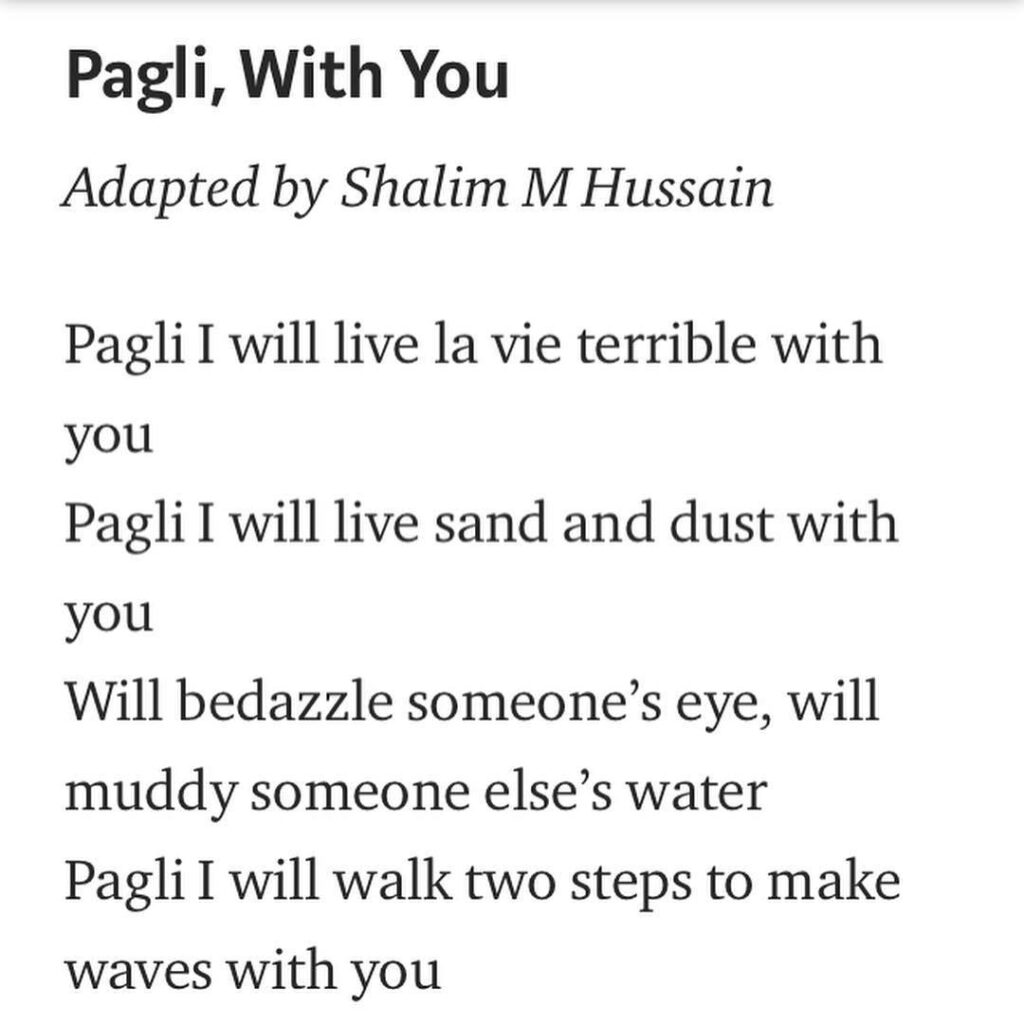

My journey with Miyah poetry, or the current phase of assertive Char Chapori poetry, started in 2016. Prior to it, I had been publishing poems for more than a decade. My first book of poems was published in 2017. Poetry as an art form came organically to me; I was looking at the world through a unique lens and had the ability to present this vision through carefully chosen words. Over the past few years, there has been a steady flow of literature from the Chars. This includes a strong collection of poems which depict the lived experiences of residents. Miyah poetry, in my opinion, is a continuation of the genre of Char Chapori poetry and its evolution. When the president of Char Chapori Sahitya Parishad, Hafiz Ahmed published the poem Write Down I am a Miyah on Facebook in April 2016, I responded to it with my composition titled Nana I have Written. Other poems were written in response to our poems and a small body of poetry emerged within a week. I realized that these were written primarily in Assamese and our local dialects which had to be translated to English so I started translating them and sent them out to literary journals and blogs. In the last couple of years, I have been writing poems in both English and the local dialect and translating both my own and works of other poets. Since then more translators have also emerged and by translating their works into other widely read languages such as English and Hindi, we have been able to reach wider audiences.

Do you think stories from Assam are under-represented?

The national media focuses only on certain parts of the country. However, if the maximum potential of social media is harnessed, stories from not just Assam but other states too can find representation. Poetry is very personal for me, when I write about the land I was born and other fiction, the stories come from my personal experiences. The documentary films I have been involved in spotlight the performing arts of the Char Chaporis. According to me, all narratives – creative, journalistic, archival and academic are equally important. Miyah poetry gives a holistic view of life in Assam and the Chars.

How has digital media been helpful in popularising Miyah poetry?

Digital media has aided in increasing reach and accessibility. For instance, one the offshoots of Miyah poetry is music videos and audio-visual recording of the poems. In August 2016, three poets started Itamugur, a YouTube channel named after a hammer-like instrument used to break hard clumps of earth before preparing the fields for sowing. That it is less aggressive and has a more meaningful purpose than a regular hammer is a telling quality of what they stand for. Their Bhatiyali music videos which have drawn great attention to the stories of the Char-Chaporis.

Do you think spoken word is more powerful to bring attention to the art form?

I am just getting acquainted with spoken word but yes, it has played a huge role in the spread of Miyah poetry. We have read our poems at different venues and received great response from the audience.

Have you been able to change people’s perception about the community through this device?

We have been able to change the perception of many people — even the residents of Assam — who didn’t know much about life in the Chars. Since Miyah poetry talks about lived experiences of love, loss, and celebration, it has been successful in bringing the ordinary life in the Chars to light. Until a couple of months ago, the representation of the Bengal-origin Assamese Muslims in media wasn’t positive; they were portrayed as thieves, dacoits and rapists. Today, we are representing ourselves appropriately through poetry regardless of others’ opinions. The narrative has definitely shifted.

You have explored various fields as a writer, poet, professor and filmmaker. Which one do you prefer?

I like being a professor. One can communicate in real-time with their audience, which puts a lot of responsibility to be careful with the selection of material that should be used in the class and the language of communication. Writing allows me to tell my own stories, so there’s more freedom. As far as film-making is concerned, I wouldn’t call myself as a filmmaker. There are some art forms I think should be documented, and I do my best.

What is the future of Miyah poetry, according to you?

As long as Miyah poems are written, the tradition will remain alive. In the absence of organisational structure, independent poets write poems and share them on social media platforms. There isn’t a formal definition of ‘Miyah Poetry’ which we abide by; poets themselves decide if their work qualifies to be termed in this genre. It is democratic, as no one decides if a work is a ‘real’ poem or critiques it as a good or bad poem. Every Miyah poet is an individual and each voice is precious for us.

*To reproduce the above poem in any form, copyright permission must be sought from Shalim.

source: http://www.vervemagazine.in / Verve / Home> Arts & Culture> Library / by Ojas Kolvankar / August 28th, 2019