Mysuru, KARNATAKA :

It was 1765 and a Duke in faraway England known for breeding race horses named his foal Hyder Ally. A few years later in 1782, and many more thousand miles away at the other end of the world, a single mast ship named Hyder Ally gave the fledgling navy of United States of America one of its greatest victories. How are these two events related and what connection did they have with the people of the erstwhile Kingdom of Mysore, the precursor to modern day Karnataka state, India?

In 1749 a 27-year old youth Haidar Ali (Hyder Ally as the British spelled his name), born at Budikote in modern day Kolar district, Karnataka put his military skills in action for the Mysore Army during the nine month siege of Devanahally Fort against a Poligor. Poligars (or Palegaras in Kannada language) were the local strong men, each controlling a few fortified settlements prior to the British rule. In early 1750s Haidar was also part of the action between the French and English in their struggle to install a person of their choice as Nawab of Arcot in which the Mysore Army sided with the English. Haidar Ali increased his stature among the military circles of the Mysore Army and was elevated asFaujdar of Dindigul in 1755. He successfully led Mysorean resistance to the Maratha invasion in 1759 and was consequently elevated as the Chief Commander of its army. Haidar’s perseverance in fighting his political foes paid off and in 1761 he was the lone survivor around the utterly weak Mysore King of the Wodeyar dynasty. He proclaimed himself a Nawab soon and found himself the de-facto ruler of Mysore Kingdom, being the most successful in protecting it from invasions by both other Indian kingdoms as well as Europeans 1. By then the British East India Company had its eyes set firmly on peninsular India having taken control of Bengal in 1757 as a consequent of the Battle of Plassey.

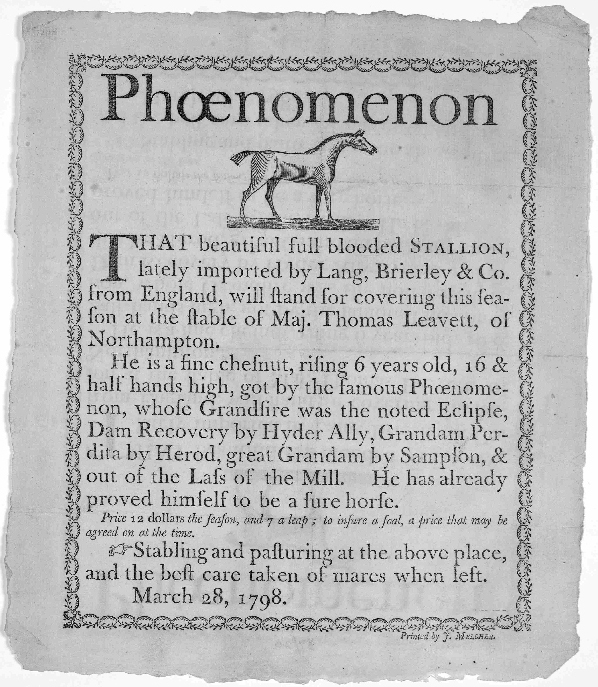

Back in England, Peregrine Bertie was the 3rd Duke of Ancaster in England having succeeded his father in Jan 1742 2. He raised a regiment of foot for the King of England during the rebellion in Scotland in 1745 3. He was subsequently promoted to the rank of a General in the Army in 1755 and later as a Lieut. Gen., in 1759 4. Peregrine was a leading horse racer who started a number of famous racing lines 5. He was appointed Master of the Horse to Queen Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland in 1765. Peregrine as a military administrator was probably aware of the military and political happenings in India. In fact he was transferred in a year from the post of the Master of the Horse to the Queen to that of the King, where he was ‘responsible for overall management of all the royal stables, horses, carriages’. This transfer was due to the changes affected by the stock-holders of East India (EI) Company in England. The stock-holders were apparently alarmed by the acts of the English Prime Minister Lord Chatham to curb the influence of EI Company which by then controlled huge resources and land across in India. Given this background Peregrine was probably informed of the meteoric rise of Haidar Ali in south India’s political and military theatre. Indeed in 1760 an overconfident English Army detachment under Major Moore tasted its first defeat at the hands of Mysoreans under Haidar Ali at Trivadi near Pondicherry. And through that decade Haidar continued to spoil the political, economic and military aims of East India Company in Peninsular India with ramifications beyond this country given the global nature of the company’s trade. Did the military acumen of this Mysorean soldier play a role in Peregrine in naming his foal Hyder Ally in 1765 6,7? This may not be surprising as another race horse breeder in England named a foal Tippoo Saib in 1769 8, 9. Just a couple of years ago in June 1767, 17-year old Tipu Sultan (or Tippoo Saib as the British preferred to call him), heading a small force of the Mysore Army, stormed East India Company’s HQ in south India at Madras and nearly imprisoned the Madras councillors who threw themselves into the sea and escaped in a dingy. A year later Tipu recovered Mangalore from the British who fled the fort leaving behind their sick and wounded 10. The military and political deeds of this father-son seem to have left an impression on the British psyche.

US Navy’s tryst with Hyder Ally

Chance a race horse imported into USA by Col. Tayloe was a line of Peregrine’s Hyder Ally 8,11. Interestingly foals within America were also being named Hyder Ally (and Tippoo Saib) in 1770s.

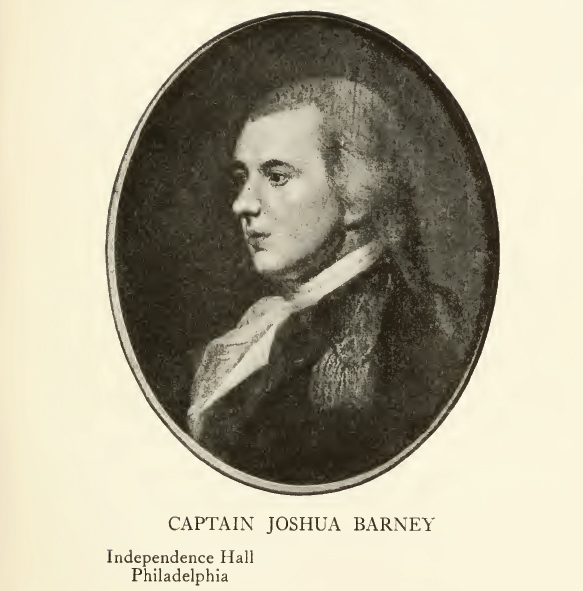

The first Hyder Ally to be foaled in America was in 1777 and four other foals were recorded with the name in 18th century 12, 13. But something very interesting was recorded in eye witness accounts of America’s history in 1770s. An upheaval overtook the country in 1775 as ordinary Americans rose against the Government of Great Britain, declared independence and flew their own flag 14, 15. Apparently the first flag of the Union, now the US national flag- the Stars and Stripes, sent to the state of Maryland was hosted on a sailboat by teenaged Joshua Barney at Baltimore in October 1775 who served the US Navy since then.

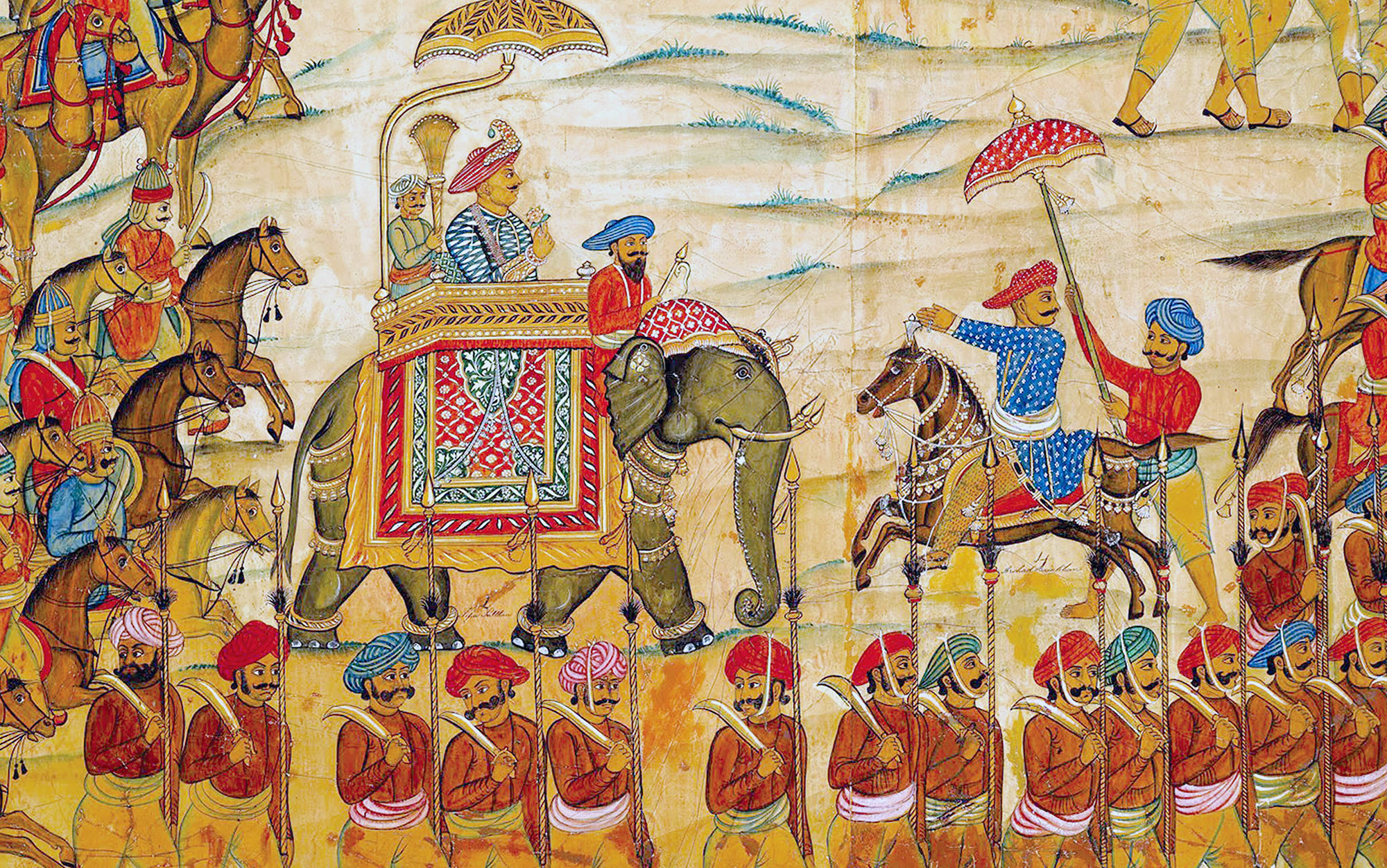

‘Rocket Warfare’, by Charles H. Hubbell (1898–1971) captures the humiliation of British at the Battle of Pollilur (Sep. 1780) by Mysorean war rockets

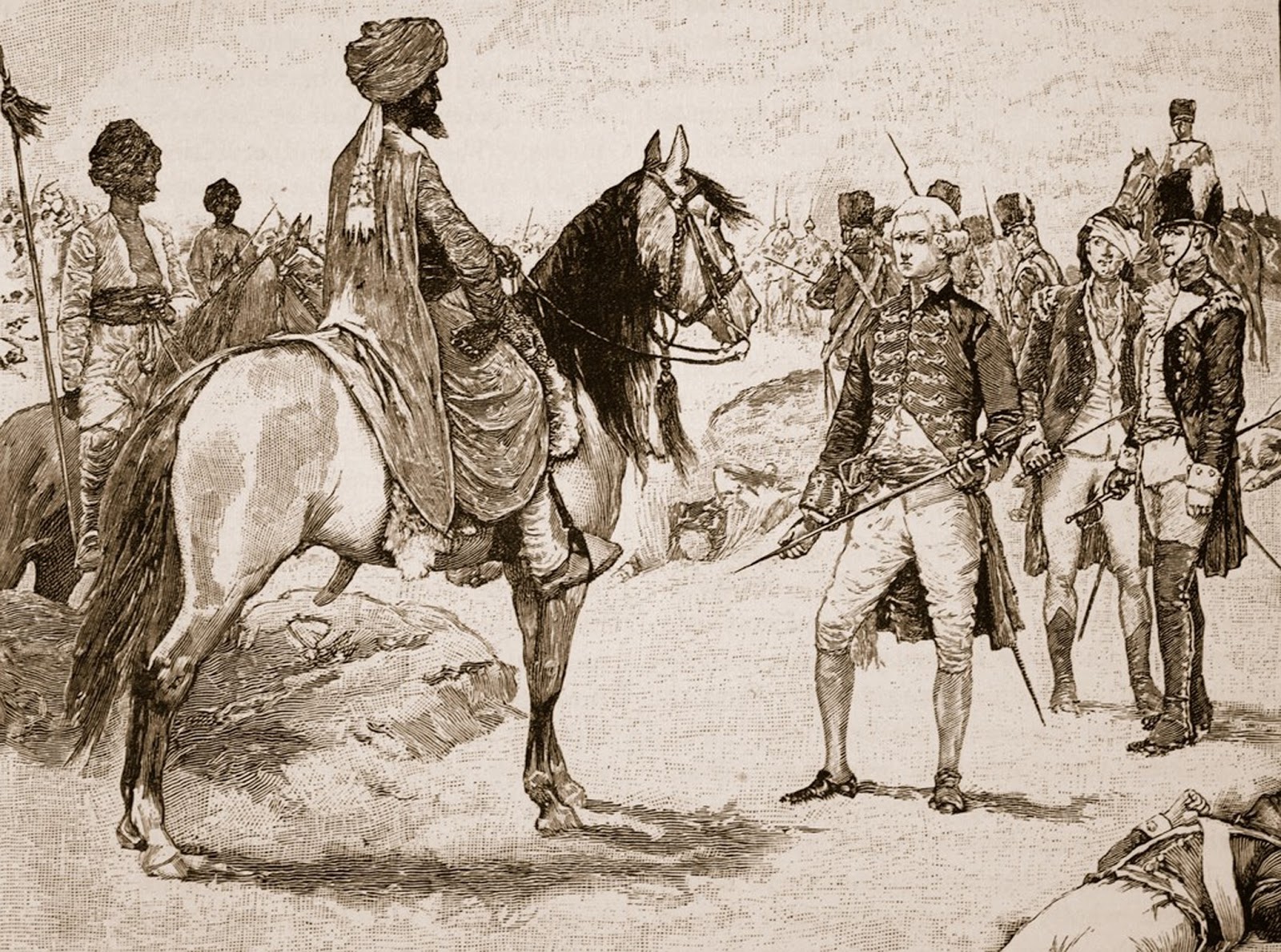

In 1780, in far-away Mysore Kingdom, America’s ally against the British through the French, the East India Company was suffering one of its worst reverses in its military history. The reverberations of the humiliation of British at Battle of Pollilur in September 1780 inspired the Americans who received the news 16 on 23 August 1781. On 19 October 1781, the British land force led by Charles Cornwallis (who later led EI Company’s army and its Indian allies to defeat Haidar Ali’s son Tipu Sultan in the 3rd Anglo Mysore War) surrendered to the Americans led by George Washington. Nine days later Cornwallis’ surrender was celebrated at Trenton, New Jersey with the town being decorated with American colours. The town’s who’s who along with inhabitants attended a service at the Presbyterian Church, where a discourse highlighting the occasion was delivered by a Reverend. In the afternoon the gathering drank 13 toasts accompanied with a discharge of artillery one of which was for ‘The great and heroic Hyder Ali, raised up by Providence to avenge the numberless cruelties perpetrated by the English on his unoffending countrymen, and to check the insolence and reduce the power of Britain in the East Indies’.

In October 1781, the British land force led by Charles Cornwallis surrendered to the Americans led by George Washington (Incidentally a decade later Cornwallis gave EI Company and its Indian allies victory over Haidar Ali’s son Tipu Sultan in the 3rd Anglo Mysore War in India). But America was far from being an independent nation. The British still ruled the seas. They kept a keen watch on the ships entering and exiting the ports of north east USA, often capturing the vessels and looting goods 17.

General Washington an American sloop-of-war was captured by Admiral Arbuthnot, and placed in the king’s service under a new name The General Monk, which was then used to pirate American ships. By 1782 the commerce of Philadelphia City as well as the ordinary life of the residents of the coast and nearby streams was deteriorating. As the fledgling American Union was not in a position to protect the affected vessels the State of Pennsylvania, at its own expense, fitted a number of armed vessels that operated in waters leading to Philadelphia. The state purchased Hyder Ally, a small sloop (single mast ship) equipped it with sixteen six-pounder guns to help protect the American vessels. 23-year old Lieutenant Joshua Barney, now in the US navy, arrived at Philadelphia where he was honoured with the command of Hyder Ally17. Assigned with recruiting men, Barney used a poem penned by Philip Morin Freneau18 to attract young American men to the ship. The poem exalted Haidar Ali’s bravery against the British with the following lines:

Come, all ye lads who know no fear,

To wealth and honour with me steer

In the Hyder Ali privateer,

Commanded by brave Barney.

From an eastern prince she takes her name,

Who, smit with freedom’s sacred flame,

Usurping Britons brought to shame,

His country’s wrongs avenging;

Come, all ye lads that know no fear.

With hand and heart united all

Prepared to conqueror to fall.

Attend, my lads! to honor’s call —

Embark in our Hyder-Ally!

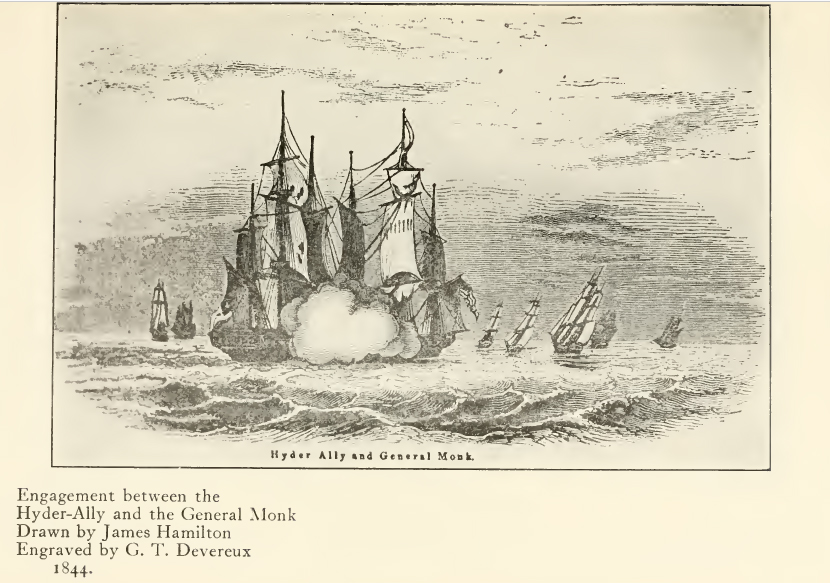

And soon Barney led a force of a hundred and ten men. On April 8, 1872, he received instructions to protect a fleet of merchantmen to the Capes just before the sea, at the entrance of Delaware Bay. Dropping the convoy at Cape May road he was awaiting a fair wind to take the merchant ship to sea when he saw three ships19 which he realised were waiting to plunder the convoy. Barney immediately turned the convoy back into the bay, using Hyder Ally to cover the retreat. Soon the bigger General Monk under the command of Captain Rogers of the Royal Navy nearly double his own force of metal, and nearly one-fourth superior in number of men caught up with Hyder Ally. Despite being fired upon, Barney held Hyder Ally’s fire till within pistol shot when both the two vessels got entangled. A desperate fight, lasting for only 26 minutes though, resulted in the lowering of flags by General Monk indicating her surrender. Both vessels arrived at Philadelphia a few hours after the action, bearing their respective dead. The Hyder Ally had four men killed and eleven wounded. The General Monk lost twenty men killed and had thirty-three wounded including Captain Rogers himself, and every officer on board, except one midshipman!20

A hero is celebrated

Philadelphia burst in celebrations. Ballads were made upon this brilliant victory and sung through the streets of the city! And echoing with Barney’s name was that of Hyder Ally. Here are some lines 14:

And fortune still, that crowns the brave

Shall guard us o’er the gloomy wave —

A fearful heart betrays a knave!

Success to the Hyder-Ally!

While the roaring Hyder-Ally

Cover’do’er his decks with dead !

When from their tops, their dead men tumbled

And the streams of blood did flow,

Then their proudest hopes were humbled

By their brave inferior foe.

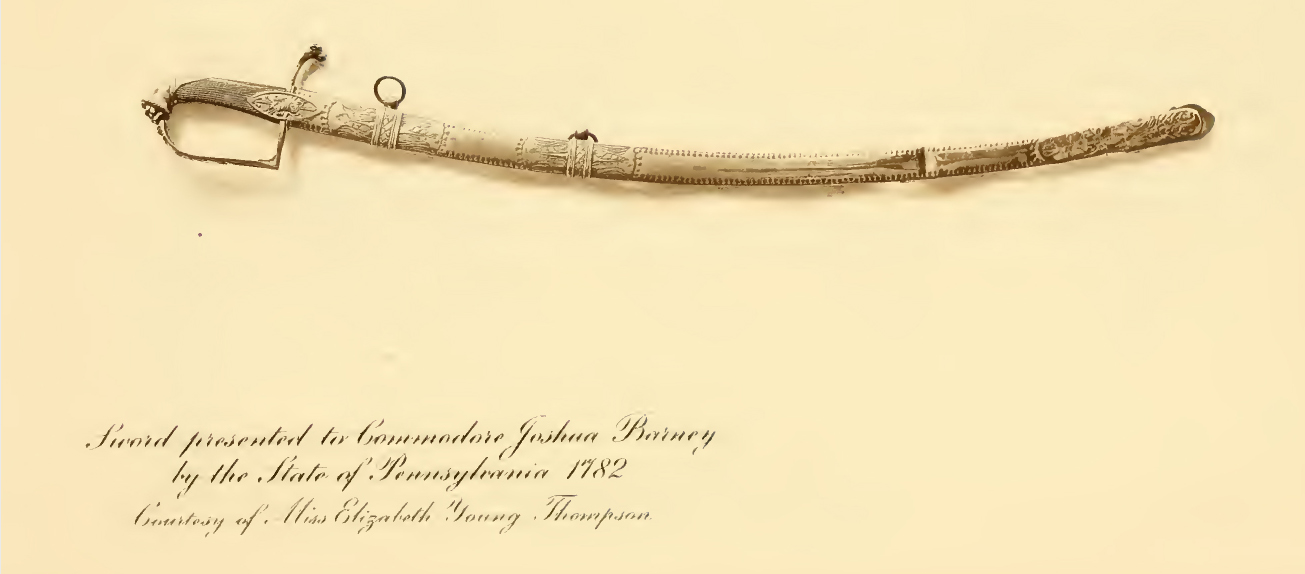

In 1782 the Legislature of Pennsylvania passed a vote of thanks to Captain Barney and ordered a gold-hilted sword to be prepared, which was afterwards presented to him in the name of the state by Governor Dickinson. It was a small sword with mountings of chased gold- the guard of which on the one side had a representation of the Hyder Ally, and on the other the General Monk 14. Barney was the last officer to quit the Union’s service, in July, 1784, having been for many months before the only officer retained by the United States.

Barney was sent by the American Government to Paris. A reception was given in France him as a hero of dashing naval exploits during the Revolutionary War 21. A painting representing the action between the two ships was executed in 1802 by L. P. Crepin in Paris by order of Barney, while in the service of the French Republic. The same was presented by him on his return to the United States, to Robert Smith, Esquire, then secretary of the navy 22. The painting is now in the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland 14. Barney was an intimate friend of Count Bertrand, one of Napoleon’s generals 15. Napolean incidentally had an alliance against the British with Haidar Ali’s son Tipu Sultan, during the latter’s life time 23.

Barney was appointed a Captain in the Flotilla Service, US Navy on 1814 April 25 24. He took part in seventeen battles during the Revolutionary War and in nine battles during the War of 1812. A British Musket-ball lodged inside his body in battle at Bladensburg, Maryland in August 1814 25. He passed away on December 1, 1818, aged 60.

70 years after Hyder Ally’s victory over General Monk, James Cooper wrote “This action has been justly deemed one of the most brilliant that ever occurred under the American Flag. It was fought in the presence of a vastly superior force that was not engaged, and the ship taken was in every essential respect superior to her conqueror.” 17

The world today is considered a global village thanks to the scaling down of boundaries between nation states and individuals alike. But it may surprise us even in the 18th century seemingly local political events and humans made an impact on lands and societies far away. The name Haidar Ali, after an adventurer from an obscure place in the erstwhile Kingdom of Mysore who gave many a lesson in military and political strategies to global colonial powers of England and France, echoing across the proverbial seven seas in distant North America for nearly a century is testament of this 26, 27.

Sources/ Notes:

- Col. Mark Wilks, Historical Sketches of the South of India, Volume 1 of 3, 1810. Wilks traces the origins and political lives of Mysore Kingdom’s rulers and provides an insight into their military campaigns.

- The New Peerage, or Present state of the Nobility of England, Vol. 1 of 4, 1784

- The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol.78, Part 1, 1808

- George Cokayne, Complete peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, 1887

- Allan Chivers, The Berties of Grimsthorpe Castle, 2010. Peregrine established the racing lines of Blank, Paymaster and Pacolet which were well-known in England. Their foals went to establish themselves in the US.

- Blank was one of his favourite horses and he named a foal sired by it as Hyder Ally.

- Hyder Ally was later sold by Bertie to C.Blake who then sold it to Richard Vernon. The later, in Oct. 1773, raced it at New Market, considered the birthplace and global centre of thoroughbred horse racing. Many of this horse’s progeny were imported into America and entered racing.

- allbreedpedigree.com Online database on Pedigree horses. Downloaded Oct. 10, 2017.

- It is interesting that it was not uncommon for race horses to have names originating in the east. Such names in 1700s included Mumtaz Mahal and Salim7. But Pergerine’s only horse named after a human was Hyder Ally.

- Prof. B Sheikh Ali, Tipu Sultan – A Crusader for Change

- American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine, Vol. 2, 1831

- J.H.Wallace, American Stud Book, Vol. 1, 1867

- Other books that document Hyder Ally foals and sires are William Pick and R.Johnson’s The Turf Register, and Sportsman & Breeder’s Stud-Book (1803) and Patrick Nisbett Edgar’s The American Race-turf Register, Sportsman’s Herald, and General Stud Book, Vol. 1 of 2 (1833)

- A biographical memoir of the late Commodore Joshua Barney (1832) by Mary Barney sister of Joshua Barney provides in-depth information of the latter’s personal and military life. Born on July 6, 1759, 13-year old young Philadelphia Joshua Barney set sail on his maiden merchant ship journey to Ireland in 1771 with his brother in law Captain Thomas Drysdale. He sailed back home the following year and made trips to ports in Europe again. He set sail for Nice, France in December 1774 during which journey Captain Drysdale died. He took control of the ship which needed urgent repairs and therefore docked at Gibraltar, Spain instead. In a few months he sailed to Algiers, Algeria from Alicant, Spain to deliver Spanish troops during which he witnessed the annihilation of these troops by the Algerians which made him return to Alicant soon. He immediately set sail across the vast Atlantic Ocean for Baltimore, USA. As he entered the Chesapeake Bay on 1st October he was surprised by the British Sloop of war Kingfisher. An officer searched his ship and informed him that Americans had rebelled and that battles were being fought. He was fortunate enough to escape detention. Returning to Philadelphia he was determined to serve the Americans fight against British. At that time a couple of small vessels were under at Baltimore ready to join the small squadron of ships stationed then at Philadelphia and commanded by Commodore Hopkins. Barney offered his services to the commander the sloop Hornet, one of these vessels. He was made the master’s-mate, the sloop’s second in command. A new American Flag, the first ‘ Star-spangled Banner’ in the State of Maryland, sent by Commodore Hopkins for the service of the ten gun Hornet, arrived from Philadelphia. At the next sunrise, Barney unfurled it in all pomp and glory. In 1776, Robert Morris, President of the Marine Committee of the Congress offered him a letter of Appointment as a Lieutenant in the Navy of the United States in recognition of his efforts during a naval battle engagement in Delaware.

- A summary of Mary Barney’s book14 is well recapped with notes in William Frederick Adams’ Commodore Joshua Barney: many interesting facts connected with the life of Commodore Joshua Barney, hero of the United States navy, 1776-1812 (1912).

- Frank Moore, ‘Diary of the American Revolution’, Volume 2, 1860

- James Fenimore Cooper in History of the Navy of the United States of America (1853)

- ‘The sailor’s invitation’, Freneau’s Poems written and published during the American Revolutionary War (1809)

- Two ships and a brig- a sailing vessel with two masts

- As explained by Barney himself in his painting of this war commissioned later

- A. Bowen, The Naval Monument,1815, Concord, Massachusetts, U. S. A. gives an account of the reception received by Barney in France

- The painting was accompanied by a description, in the hand-writing of Commodore Barney, which is reproduced in Mary Barney’s book

- Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD, https://historyofislam.com/tippu-sultan/ (downloaded October 13, 2017)

- Record of Service, Bureau of Navigation, Navy Department, United States Navy

- The conduct of Commodore Barney, at the battle of Bladensburgh, was appreciated by his military opponents as well. He was wounded in the engagement and was taken prisoner by General Ross and Admiral Cockburn but paroled on the spot. At the time of his death in 1818, the ball was extracted and given to his eldest son. For the valuable services of her husband, Congress granted Mrs. Barney a pension for life.

- William Goold, Portland in the past, 1886 has information of at least one more well-known ship named Hyder Ally built in the US in 1800s after the one described in this story. This ship, like many other US ships, resorted to pirating British ships in the Indian Ocean all the way up to the island of Sumatra and around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa in the run up to the British-American War of 1812.27. Corbett’s Annual register (1802) documents the ship ‘Tippoo Saib’ registered in Savannah, Georgia, the southern most of the 13 colonies that declared independence from the British in 1776 and formed the original ‘United States of America’.

A version of this story was published on Nov. 20, 2017, in Deccan Herald, Spectrum supplement, Bengaluru http://www.deccanherald.com/content/643780/when-america-celebrated-mysorean-name.html

source: http://www.historyofmysuru.blogspot.com / November 25th, 2017