UTTAR PRADESH / NEW DELHI :

Dr Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari was a staunch Congressman and author of a book titled ‘Regeneration in Man’. Wednesday marks his 81st death anniversary.

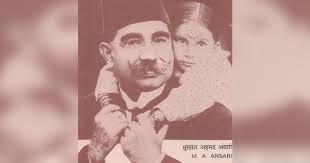

India’s political leadership during the British Raj was dominated by lawyers and journalists. A noted exception was Dr Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari (1880-1936), one of Delhi’s richest men, who dexterously balanced his busy medical practice with a deep involvement with politics.

Ansari was a close companion of Gandhi and an icon of the Khilafat movement. The few scholars who have studied his life have focused solely on his role as a Congress leader, and on his skills on the negotiating table of high politics. His exploits with the scalpel have been ignored. More than 80 years after he died, on May 10, 1936, it is remarkable that forget any serious study, there is hardly any discussion about the hundreds of operations he conducted in India in which he grafted animal testicles – from bulls, monkeys and sheep – onto human beings.

Adviser to princes

Dr Ansari studied at Queen’s Collegiate school in Benares and at the Muir Central College in Allahabad (which was later incorporated into Allahabad University). He later joined the Nizam College in Hyderabad where he was given a scholarship in 1900 to study medicine in the UK. After earning a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh, he worked in London at Charing Cross hospital, the Lock Hospital and St Peter’s Hospital. He returned to India in 1910, and set up his practice in Calcutta before shifting to Delhi.

He acted as medical adviser to the princes of Alwar, Rampur, Joara and Bhopal. His two older brothers were well-known hakims, who practised the traditional unani system of medicine. They were close to the scholars at the respected Islamic school in Deoband. His own circumstances and family background proved crucial in his positioning as a key functionary during the Khilafat movement of 1919. This movement was launched by Indian Muslims to urge the British government to preserve the authority of the Turkish Sultan as Caliph of Islam with the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.

A new science

Along with his political activity, Ansari turned his mind to a matter that has obsessed physicians for centuries: the quest for medical interventions to help ageing clients produce heirs. In the early 20th century, medical journals in Europe and America were increasingly documenting cases of xenotransplantation – the transplantation of living cells, tissue or organs from one species to another. It was through such articles that Ansari became interested in this field.

In his role as a medical practitioner, Ansari was also constantly faced with a large number of patients suffering from a “real or imaginary decline in their mental, physical and sexual powers”. His brothers attempted to treat such with traditional medicines. But Ansari looked to Europe for possible answers.

In 1921, 1925 and 1932 he visited Vienna, Paris, Lucerne and London and spent a considerable amount of time in laboratories, hospitals and clinics. He met and observed urologist Dr Robert Lichenstern, Eugen Steiach, Dr Serge Voronoff – all of whom are considered pioneers in the field of grafting animal testicles onto humans. He also collected vast amounts of literature on the subject, sourcing books and journals from Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria and the US.

This procedure may now be ridiculed but in the Roaring Twenties there was quite the rush of men wanting to undergo these regenerative surgeries. Ansari offered a treatment to his clientele in India that was only available to the elite in the West.

Rejuvenating the nation

According to Ansari, there were a few key reasons why the people of India suffered from poor health. These included unhygienic surroundings, poverty and the lack of medical facilities, as well as seclusion and segregation of the sexes, and rules confining the choice of marriage partner to a limited circle.

In his 1927 presidential address to the Congress in Madras, he dwelt on the problem of healthcare in India.

He said:

“Sixty percent of the revenues of India is absorbed by the Military Department in the name of Defence of the country but the government ought to know that there can be no defence of the country when people are allowed to exist in such a state of utter physical degeneration. The real defence lies in tackling the problem of manhood and improving the general health of the nation.”

In the last decade of his life, Ansari conducted such testicle grafting operations on around 700 people. These included property agents, merchants, jewellers, bankers, provincial civil servants, sportsmen and labourers.

In a letter to Aziz Ansari, his cousin, the doctor wrote that Eugen Steinach “urged me to publish my researches (sic) and not to hide my light under the bushel”.

Ansari meticulously noted down around 440 cases of grafting that he had done. He monitored or kept in touch with these individuals for a period of three to four years after the surgery. In one case, he wrote that a wrestler whose testicles were badly damaged by an opponent and lost his “sexual power” for eight years underwent grafting and found that his sexual appetite was restored. In another case, a man in his early 50s, who was a heavy drinker and had contracted sexual diseases in his 30s, found his health to be deteriorating drastically. After Ansari grafted slices of a bull’s testicles onto the man’s gonads, he gained weight, became healthy, and started leading a normal life with a new wife. Through such case studies, Ansari emphasised that his surgeries resulted in the rejuvenation of patients, which added to the productivity of the nation.

He gave Gandhi a copy of his book Regeneration in Man, who read it with great interest in one day. Describing it as evidence of “research and great labour”, Gandhi, whose aversion to western medical practices is well known, asked his friend: “What is revival of youth worth if you cannot be sure of persistent physical existence for two consecutive seconds?”

But for the short, well-built, moustachioed doctor who played the role of Othello in a play while a student at the University of Edinburgh, these procedures were part of a larger vision for a “universal campaign against the disability of old age”.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home / by Danish Khan / May 10th, 2017