Murshidabad, WEST BENGAL :

When Suvendu Adhikari crossed over to the BJP, it was said there’s no reason to fuss over the desertion of Mir Jafars. Now actor Rudranil Ghosh has earned the sobriquet of Mir Jafar 2.0. But what is it to be the progeny of a man-turned-pejorative?

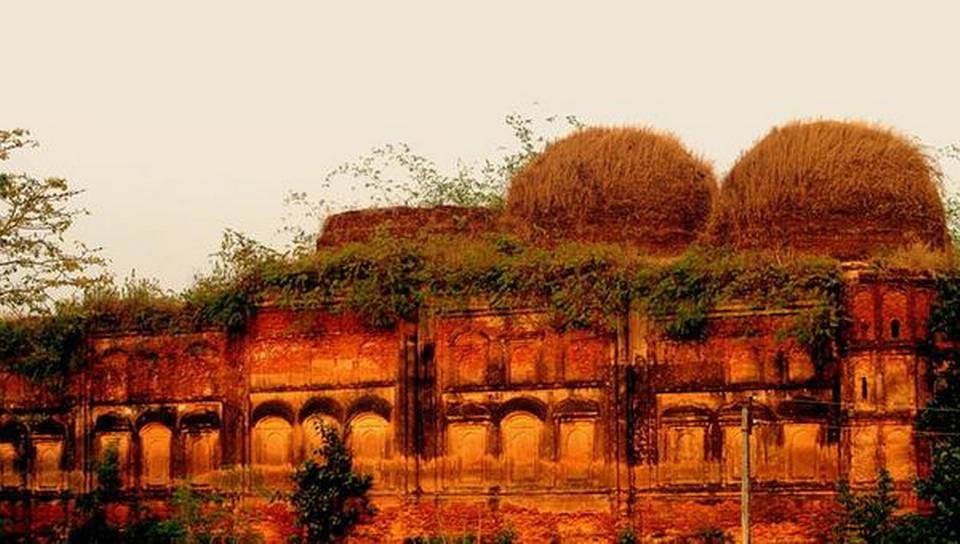

The setting of this story is Lalbagh, a locality in Murshidabad, erstwhile capital of Subah Bengal or present-day Bangladesh, Bengal, Bihar and Odisha. According to the book The Musnud of Murshidabad (1704-1904), “Being more conveniently situated than Dacca for the collection of revenue and the supervision of trade… Murshed Kuli Khan, the Great Dewan of Bengal, selected it as his headquarters and embellished it, giving it its present name after his own.” This was in the early 1700s.

Thirty kilometres away from Lalbagh is Plassey, and Calcutta is 200 kilometres away. The nawab’s estate here has an enormous entrance; it was designed such that stately elephants could saunter through. To its left there is a two-storey stretch limo of a building punctured with countless square windows. “It is the house of the Bade Nawab and the Chhote Nawab,” says local guide Swapan Chowdhury. Yes, the Government of India abolished the princely order in 1971, which means titles are not recognised; but the usage endures in various orbits of society to suggest legacy, status or power, oftentimes as veneer on a less grand present.

The two “nawabs” are among the living descendants — eighth generation to be specific — of Syed Mir Jafar Ali Khan Bahadur, commander of the Bengal army under Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah. He whom we today know as Mir Jafar, shorn of all gallantry, accomplishments and grandeur he might have been associated with once. The same who is synonymous with the betrayal he perpetrated on the young Siraj in Plassey in 1757.

And so you have — mir jafar (n) once man, now pejorative; most commonly used Indianism for traitor or turncoat.

***

Syed Mohammad Reza Ali Meerza or Chhote Nawab greets me as he hurriedly picks a white kurta from the clothesline and slips it over his head. “This is the building that housed the sentries during Mir Jafar’s time,” says the 79-year-old.

Reza Ali has worked as a state government employee all his life. “My tenure as a permanent employee fell short by a few days and that’s why I do not get any pension, etc.,” he lets slip a crib and thereafter quickly arranges some plastic chairs, and with a wave of his hand and a “tashreef rakhiye” continues his narration.

Pointing to the recently installed statue of Siraj ud-Daulah bang opposite his house he says, “Siraj ke aami khoob bhalobashi… I love Siraj very much. People say Mir Jafar betrayed him. Bhul bole… that’s wrong.”

And yet from what he says, it is clear this is one “wrong” he and his kin have trouble living down even today. Tourists, visitors, researchers, all continue to raise eyebrows when they learn about the family tree. What about locals? He replies, “Oh! People here love me. They say: ‘We do not care about Mir Jafar. We know you are a good human being’.”

He offers a quick tour of the andarmahal. There are pictures and memorabilia aplenty littered all over. Is any of this Mir Jafar’s?

No. Most of the belongings of the nawabs are kept in the museum inside Hazarduari Palace. That collection includes Mir Jafar’s sword, shield and dagger, his footwear, the cutlery he used.

The Hazarduari Palace, Wasif Manzil, and Begum Manzil are all part of the nawab’s estate. Reza Ali offers to take us around. On our way out, we meet Syed Mohammed Abbas Ali Meerza, or Bade Nawab.

Abbas Ali has a persona quite distinct from his younger brother’s. He is of reserved bearing and stands on ceremony. He is quick to inform that, in 2013, he won “the case” in the Supreme Court and since then he and his brother have been recognised as genuine claimants to the title of the Nawab of Murshidabad.

Without the prodding, Abbas Ali starts talking about his ancestor. “Who says Mir Jafar was a traitor? Mir Jafar hails from the Najafi dynasty. We are the direct descendants of Prophet Hazrat Mohammad.”

The Najafi dynasty was born when the Prophet’s grandchildren Hasan and Husyain’s children married. Abbas Ali explains, “Hasan’s son Hassan e Mussanah and Husyain’s daughter Hazrat Fatimah Sughra married. And then the Najafi dynasty was born. We are the descendants of Husyain Najafi. His son Ahmad Najafi was married to Zinnat-un-Nissa, daughter of Shah Jahan’s son Dara Shikoh. Mir Jafar was their son.” He adds, “Mir Jafar was much higher in status to Siraj ud-Daulah, both by bloodline and given that he was the son-in-law of Alivardi Khan, the nawab of Bengal and grandfather of Siraj.”

Says Abbas Ali, “Had he wan-ted to kill Siraj, he wouldn’t have had to go through all the drama of Plassey. He could have got the musnud (throne) from the Mughal emperor himself.”

Dr S.M. Reza Ali Khan is another descendant of Mir Jafar. The Telegraph had interviewed him in January 2020; months later he died. Khan was a professor of history and had done a lot of research on the Battle of Plassey and Mir Jafar. He had said over phone from Hyderabad, “The ignominy attached to this name does not give us a good feeling.”

Dr Khan believed it is not quite right to judge Mir Jafar by cutting him away from the age he belonged to, the environment and those circumstances. He had said, “It was the 18th century and there was no concept of nationalism. And even if there was, let me tell you Siraj was not a great nationalist either. Besides, he had killed his own brother, his uncle and even the husband of Alivardi Khan’s eldest daughter, Ghaseti Begum, to get the musnud.”

Through the lockdown Dr Khan would call many a time with this reference and that reference from history texts. He spoke about the Sheths of Murshidabad, a very powerful community in the 18th century. They did business with French and British traders. Jagat Sheth Mehtab Chand, one of the most prominent businessmen of Murshidabad, used to lend money to the British at a steep interest. Dr Khan had said, “When Siraj declared the British as his enemy, Mehtab Chand could not have been very pleased. His business would have been hampered.” It seems a fair number of Sheths had stood up against Siraj.

Abbas Ali too spoke about Siraj’s unpopularity. Siraj had planned to kidnap the daughter of Rani Bhabani, the queen of Nator. “This was not well received by the Hindu nobility… Siraj had insulted Mir Jafar once in the durbar by having his beard shaved off.”

Octogenarian Baquir Ali Meerza is yet another descendant; he too is based in Lalbagh, but in Kella Nizamat. He says, “It is true we have to suffer the ire of people because the history books say Mir Jafar did not fight in the Battle of Plassey. But these books do not say why he did not fight.”

In The Black Hole of Empire, Partha Chatterjee cites from the Fort William Select Committee Proceedings of May 1, 1757. It reads, “The Committee then took into consideration, whether they could (consistently with the Peace made with the Nabob) concur in the measures proposed by Meer Jaffir of taking the Government from Souragud Dowla, and setting himself up…” Sometime end-June, the British won Plassey. In the same book, Chatterjee writes, “The battle was over by the fall of dusk. The next day, Clive wrote to Mir Jafar: ‘I congratulate you on the victory, which is yours not mine…’”

Baquir Ali’s version differs. He says, “Mir Jafar’s tent was closest to the British forces. The British had come to fight the French, not Siraj ud-Daulah. Armed with only 2,000 soldiers, they came to Plassey and found that Siraj was waiting there with an army of 20,000. The French army stood in front of Siraj’s camp. Mir Jafar’s camp was far away.”

According to him, the British approached Mir Jafar and asked him to mediate with the nawab. Mir Jafar sent a messenger to Siraj but it would have taken a day to cover the distance. In the meantime, the French army opened fire. The British mistook it as Siraj’s rejection of their proposal and retaliated. “Mir Jafar was confused and did not know what to do… What happened at the battlefield of Plassey is a case of misunderstanding and not betrayal,” says Baquir Ali.

The Telegraph asked Abu Taher Khan, the Trinamul MP from Murshidabad, his views on Mir Jafar. A guarded Khan replied, “In this atmosphere it is best I don’t comment on Mir Jafar… But it was because of Mir Jafar that our country lost its independence. Many people say, ‘These people come from the land of Mir Jafar’. Anyone can understand in what context it is being said.”

On my way back from Murshidabad, I make two more stops — Mir Jafar’s palace and his tomb. As it turns out, there is no trace of the palace, only remains of what used to be its gates. The place is still referred to as nimakharam deuri or traitor’s gate. The Jafarganj cemetery that houses the tomb is also closed that day. The auto-rickshaw driver who has driven me around says, “Earlier it was always open, but then tourists would come and spit on it, kick it. That is when the local administration had it walled; a gate was installed.”

Locked too behind that gate are the graves of Heera and Panna, actors of the era’s dubious games of estate and empire. Falcons both, Heera and Panna flew spying sorties for the house of Mir Jafar — to the Siraj camp or, some say, to the British battlements, who knows? They were both killed in the line of duty, shot out of the skies — some say by Siraj’s marksmen, others that it was actually the British, who knows? Both were dear enough to be accorded resting places at the back of where Mir Jafar lies — to that there is sacrophagal evidence. The rest is contrary apocrypha, pick your version. That’s often the case with history too, narratives compete, interpretations duel.

I remembered what Abbas Ali had told me, “The British wrote our history. What I don’t understand is why the nawabs after Mir Jafar did not take it upon themselves to put out their version. If only…,” his voice had trailed off.Bloodline

Mir Jafar had three wives

Shahkhanum Begum

Offspring:

Fatima Begum and Mir Miran

Mir’s son is Murtaza Khan

Murtaza’s son is Mustafa Khan

Mustafa’s son is Asadullah Khan

Asadullah’s son is Azam Ali Khan

Azam’s son is Faiyaz Ali Khan

Faiyaz’s son is Jafar Ali Khan

Jafar’s son is *Dr S.M. Reza Ali Khan

Munni Begum

Offspring:

Nazam ud-Daulah

Saif ud-Daulah

Both died young

Babbo Begum

Offspring:

Mubarak ud-Daulah

Mubarak’s son is Babar Jung

Babar Jung had two sons, Ali Jaj and Wala Jah

Wala Jah’s son is Humayun Jah

Humayun’s son is Firadun Jah

Firadun’s son is Hassan Ali Meerza

Hassan Ali’s son is Wasif Ali Meerza

Wasif Ali’s daughter, Sahibzadi Hasmat-un-Nissa, married Sadiq Ali Meerza

Sahibzadi’s sons are

*Syed Mohammed Abbas Ali Meerza and

*Syed Reza Ali Meerza

*Descendants quoted in the story

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph Online / Home> Big Story / by Moumita Chaudhuri / January 17th, 2021