Aligarh, UTTAR PRADESH:

I can only write about a country that is dead and gone, Zeyad’s book is about living in the corpse of a body politic that has abandoned even the desire to be fair and just to all its citizens.

It is impossible for me to dispassionately review Zeyad Masroor Khan’s evocative memoir, City on Fire: A Boyhood in Aligarh. Both of us were born in Aligarh, my first novel and his memoir are both set in the city, and the earliest of our memories are those of Hindu-Muslim riots. In my case, it was a riot in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, where a policeman had called my father’s colleague to tell him that the police cold not guarantee our safety. We were the only Muslims in the ONGC colony, and my father was on the oil rig. A Muslim boy and a Hindu girl had eloped. Men and boys with something to prove were out with swords, so Khan uncle smuggled my mother, my elder sister, and me in the dead of the night.

These similarities, however, are swamped by the differences. We were both born in houses our grandfathers built – in my case it was on the Civil Lines part of the city, where my grandfather served as the chief medical officer –and was one of the set of houses my grandfather bequeathed to his sons. Muslims in this area – except for some university students – were those whose families might have a member in the bureaucracy. And as the Sachar Committee Report highlighted in 2005, Muslims accounted for only 2.5% of the bureaucracy.

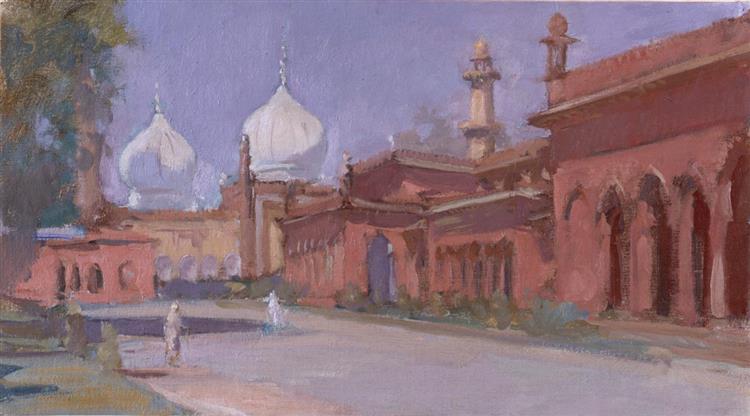

In Zeyad’s case, his house was built by, “Ashfaq Ahmed Khan, and his brother, Aashiq Ahmed Khan… from a nearby village” that was shared by his progeny. Khan’s house, where Zeyad grew up, was grandly named Farsh Manzil, with Farsh referring to the ground between heaven and earth. But it was also in Upar Kot in the commercial city or sheher.

Civil Lines is mostly known for Aligarh Muslim University, a somewhat elitist institution, while the sheher is known for locks crafted by hard-working labourers. Very few of those in the sheher, particularly the Muslims who were largely part of an underclass, received a good education, fewer still made it to the university. The small bridge, memorably named the Kathpula or half-bridge, is a border as real as that between different countries. One could cross it, but only reside in one part.

The difference was stark. When I was at the university in the early 90s, I did not attend classes, beat up my seniors, and eventually flunked out; Zeyad was a topper. Riots meant that the university was swamped by hundreds from the Rapid Action Force in their blue camouflage uniforms meant to make them visible. In Upar Kot, it was hand-to-hand combat, painfully illustrated by the chapter titled “The Button” in Zeyad’s book. There was a button in Zeyad’s house – which abutted the Hindu areas – that he once pressed as a child after climbing a chair. Unknown to him, it was linked to a lightbulb that alerted the neighbours against rampaging mobs coming to attack and kill them. The police, much less security forces like the RAF, were never there to protect the people (although, to be fair, even in the university they were seen more as a tool of repression). Instead, for Upar Kot residents, the police were often seen as part of the mob, firing on the Muslim areas.

Throughout the nearly 300 pages of the memoir there is only one mention of a policeman actually doing his duty. And that was from a childhood prank his mother and her friends pulled to get Zeyad to report that he was “lost” at the Numaish (something like an annual circus fair) so that they could see his cute face on the newly installed TV screens.

It is hard to overstate how real and important this is. For the vast majority of Indians, and the overwhelming majority of Muslims – let’s not even talk about Kashmiris or Dalits and those we call “tribals” – the state is absent, or sometimes overtly hostile. “We, the people of India” might be the first words of the constitution, but that “we” has hardly any power over, and any (good) expectation from the state in which they find themselves.

Nonetheless, the power of people “just doing their jobs” cannot be overstated. They are the one and only source of hope in the long journey from riot to riot that Zeyad maps. There are two outstanding heroes in the book. One, Bablu, is the rather slow-witted but intensely brave bus conductor on their school bus. Surrounded by a stone-pelting crowd after the bus has dropped off the Hindu children, Bablu single-handedly staves off the mob baying for blood, keeping the door closed, and showing off his Hanuman locket to show he is Hindu, and claiming that all the people inside are as well. Much, much later, a Hindu Ola taxi driver in Delhi during the 2020 pogrom drives Zeyad and his friend from a Hindu majority area to Jamia, unwilling to fall prey to the binaries and the hatred being pumped out on social media. Bablu is never recognised or rewarded for the amazing courage he shows, except maybe the grateful love of other bus passengers like Zeyad who carry a portrait of his valour in their hearts. The Ola driver would probably be attacked if identified.

Along the way, there are also others just doing their job that sustain Zeyad and open the world to him. This includes the storeowners who rent out comic books that open up a world of imagination to him; Father Joseph, the vice-principal at his school who promptly orders the removal of an article on display depicting the Prophet since some of the Muslim children found it disturbing; and Usha Aunty who rents him and his friends a flat in Delhi allowing them to live a “normal” life. There is also his teacher, Sara Job, who counsels him after he writes a provocative essay on Osama bin Laden in school, setting off an intense debate about his suitability among the schoolteachers.

What is entirely missing though, is politicians or leaders carrying out their constitutional duties. The only politician that appears is one filled with hatred towards Muslims. This is the other difference between Zeyad’s vision and mine, and it is a matter of age. I turned eighteen a few weeks after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, Zeyad was only four. In my novel set in Aligarh, the celebration of hate was an anomaly, a breakdown and a source of confusion even if communal violence was well known (my father had gone to assist people after the first major anti-Muslim riot after independence, in Jabalpur in 1961). In Zeyad’s time hate against Muslims has become a national passion. I can only write about a country that is dead and gone, Zeyad’s book is about living in the corpse of a body politic that has abandoned even the desire to be fair and just to all its citizens.

It is remarkable, then, that the book is as compulsively readable as it is. The bleakness of the terrain that Zeyad inhabits is undercut by his own humanity and humour – quite often about his own failures as well as the foibles and problems of those among whom he lives. Resilience is too often used as a word with little content. Talking recently to a friend – a Hindu, I might add – who worried whether it was even possible to just do her job, to honestly work in an atmosphere of constant baiting and attacks, I found I had little advice to offer her except to say that oppression is expensive. In Zeyad’s moving memoir, in which he returns repeatedly to how people emerge after rounds of communal violence to buy and sell to each other, to just live, even among people they have seen call for their deaths, there is an almost superhuman quality to this “resilience”. We ask much of Indians living in burning cities, demand more than humanity should bear. They shame us by giving more.

Omair Ahmad is an author and journalist.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Books / by Omair Ahmad / November 29th, 2023