Agra, UTTAR PRADESH / NEW DELHI :

The women’s writings and paintings collected here pose fundamental questions about the relation between art and marginality

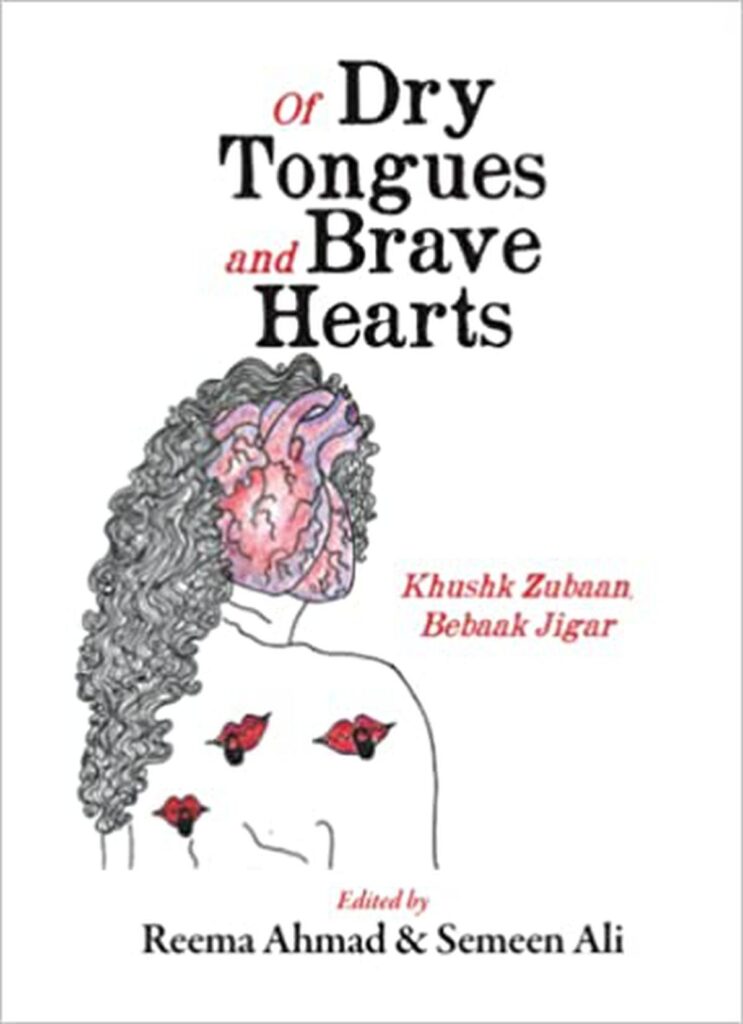

When tongues run dry but hearts remain fearless — can there be a plight direr than this tearing apart of body and mind? The drought on the tongue is the silence of fear, hiding a heart that rails against terror, pledging to shatter the quiet. Reema Ahmad and Semeen Ali have come up with a dream title for their edited collection of poetry, prose and painting by women, many of them newer voices, some unheard before, published by a daring and often-experimental publisher of poetry, Red River.

This jagged collection poses fundamental questions about the relation between art, passion, marginality, and the vagaries of everyday life. With close to 150 contributions combining verse, narrative, reflections and images, the heart of this book is filled with courage, and tongues remain dry no more — they spill rivulets of passion, anger, love, protest, and triumphant celebrations of the quotidian.

Hope is a lie

The sheer range reimagines the relation between creativity and passionate selfhood through a spectrum where the accomplishments of craft are uneven. But the honesty never is, and since in the end, honesty occupies the true heart of artistic craft, it also invites us to broaden our understanding of technical finesse beyond the usual and the expected.

Early in the collection, Debolina Dey confesses that “These poets have taught me/ to be a ruthless hunter of metaphors/ as if your body/ could be something else.” The body returns in its quotidian oppression in Sukla Singha’s story, ‘That ‘90’s Show: Blood, Shit and Other Things’, chronicling the daily humiliation, of body and labour, of a mother, experienced and narrated by a young daughter, but ending with the strange billowing of the heart: “A storm of jet-black hair in the air. A Meitei woman’s boisterous laughter. Nobody had the guts to ruin that magic.”

The vernacular is not only the name of reality here, but also of synergy between languages. Namita Bhatia’s Hindi poem, ‘Cactus’, opening with the eloquent grunt, “Mai cactus hun — cactus”, ends, in Reema Ahmad’s translation, with the “chaste hope” “That if my skin be peeled off/ I may bleed only milk”. But in her engrossing short story, ‘An Obscure Life’, Ketaki Datta reminds us that often hope is a lie — that her friend Swapna who claimed to a hotel singer had died without ever becoming one, after a life of prostitution known only to her mother.

In this dry-tongued world, poetry, as Sneha Roy knows, is a forever transgression: “Like a pillar of ‘shameless poetry’ standing tall/ in Plato’s failed and banished world.” Poetry lies in the humble and the mundane, not in flamboyance, as in Aratrika Das’s dream that her son grows up to cook in a kitchen of daily, soiled labour, not in the TV kitchen with glamorous aprons and hi-tech gadgets.

Haunted by sensation

Bodies are real and unruly in this collection. In her poem, ‘On Carving a Watermelon’, Yashasvi Vachhani voices a woman whose lover tells her: “you have a pretty face, if only you lost some of it/ some of the meat that calls your bones home”. As that “piece of art inedible”, she watches as “you hand me a knife/ and say begin”. Zehra Naqvi, in a poem of visual experimentation, reclaims the female body away from male desire and maternal nourishment: “Because our breasts belong to us. Not to the men who desire us. Not to the children who feed on us.” Dipali Taneja writes about the ageing body haunted by memories of sensation: “You hear that your uterus is senile!/ It may well be, but your skin is not.”

The lines face Teena Gill’s painting, Dancing Woman, and the meditative trance on her face strangely intensifies the bodily sensation in Taneja’s poem. Ikilily of Pink Lips, in Neha Chaturvedi’s ominous fairy tale of that name, nurses a curse — she can have sex, but if “so much as a thought of love entered her mind about the man or the woman she was with, the person would die.”

The myth contrasts sharply with the sculpted realism of Shamayita Sen’s poem, ‘Consent’, which states: “The birdcage in your chest/ will have to ask for consent/ for mine to respond.” Till the very end, the ineluctable violence of desire shapes the paradox of Khushk Zubaan, Bebaak Jigar.

Of Dry Tongues and Brave Hearts; Edited by Reema Ahmad & Semeen Ali, Red River,₹599

The reviewer’s most recent book is The Middle Finger, a campus novel about poetry, performance, and mentorship.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Mixed Collection / by Saikar Majumdar / April 02nd, 2022