Bahraich, UTTAR PRADESH :

Shahid Amin, one of India’s most creative and learned historians, explores Indian syncretism through the legend of an 11th century warrior-saint.

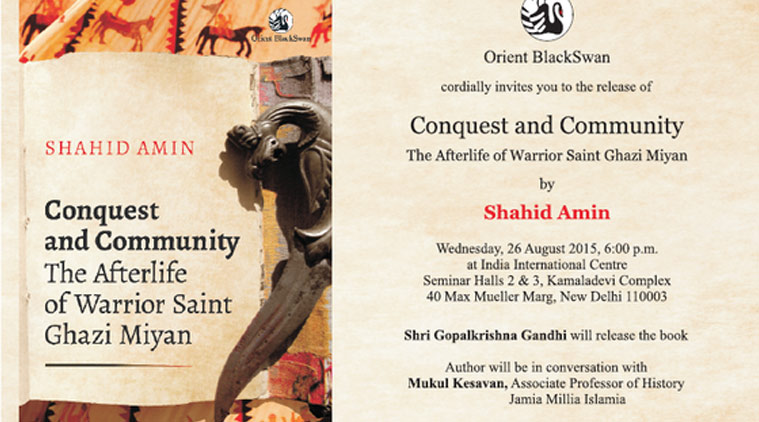

Book- Conquest and Community: The Afterlife of Warrior Saint Ghazi Miyan

Author: Shahid Amin

Publication: Orient BlackSwan

Pages: 348

Price: Rs 850

Three decades ago, the historian Shahid Amin wrote a brilliant piece, ‘Gandhi as Mahatma’, which is in many respects the locus classicus of what became the subaltern school of Indian history. What he offered was far more than what is ordinarily called “history from below”, showing that the masses made of Gandhi what they could, stepping outside the role habitually assigned to them by nationalist historiography. The Mahatma, Amin suggested, had been metamorphosed into a floating signifier.

In the present work, Conquest and Community, which cements Amin’s reputation as one of India’s most creative and learned historians, he extends this mode of analysis and turns his attention to Salar Masud or Ghazi Miyan as he is more popularly known, a warrior saint whose cult appears to have been well established by the 14th century.

The story of Ghazi Miyan begins, we may say, with Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, whose name is calculated to turn the middle-class Hindu into a figure of rage: this early 11th century warrior made repeated incursions into India, “utterly ruined the prosperity of the country” and desecrated the shrine of Somnath. Folklore would inscribe a place for Salar Masud as Mahmud’s nephew, though contemporary records make no mention of such kinship, and representations of him as a warrior taking up arms on behalf of his uncle until he was felled in battle in 1034 against a confederation of Hindu kings began to proliferate.

More surprising still is the fact that the Ghazi was transformed into a Sufi saint, the extent of whose following and reputation might be gauged by the presence at his dargah of Mohammad bin Tughlaq, the Sultan of Delhi. Abdur Rahman Chishti’s 17th century hagiography, Mirat-i-Masudi, would displace Mahmud with Miyan Ghazi. To this day, the cult of the 11th century Indo-Turkic warrior saint thrives in north India, and Hindus and Muslims continue to be drawn in large numbers to his dargah at Bahraich.

Just how is it that the popular assent to the cult of Ghazi Miyan was garnered across the religious divide, and that too with respect to a figure associated in educated Hindu minds with the image of the rapacious Muslim invader? Amin says rather modestly that his “book eschews definitive explanations” and that he is not interested in asking why a 17th century Sufi wrote the text “at the time that he did,” or why “Hindu castes felt no compunction in installing a Muslim warrior on their domestic altar”.

He sets out, rather, to explore those aspects of the Ghazi Miyan narrative which took hold firmly in Gangetic popular culture. This leads him knee deep into some extraordinary anomalies. The commonplace view of Muslims in India renders them as beef eaters, but the Ghazi Miyan of folklore is a protector of cows, the saviour of oppressed cowherds, and a determined foe of the landlords who claimed as their prerogative the right to impregnate the virgin daughters of the Ahirs. In a similar vein, the ballads celebrate the story of the married Brahmin woman, Sati Amina, at whose home the sandalwood tree has dried up.

The family priest avers that the tree will regenerate upon the Ghazi’s arrival — and so it does. In gratitude, Amina washes the feet of the Ghazi and his followers, the Panchon Pir, and then serves them a lavish meal. What could be more violative of the social order than for a Brahmin woman to cook for a Muslim man? Yet, as the very name Sati Amina signifies — Amina is the Prophet’s mother — this is a story about in-between spaces and the risks (and pleasures) of transgressive and forbidden acts.

By the 19th century, as Amin shows, the cult of the Ghazi had become a source of acute anxiety to British, Muslim, and Hindu elites alike. Colonial ethnographers and officials had set out to clearly differentiate “Hindu” and “Muslim” communities, and the presence of a large number of Hindu worshippers at the sites associated with the Ghazi was immensely bewildering to them. On the specious ground that Bahraich was a “cosmopolitan” site and therefore not deserving to be characterized as a special religious endowment of the Muslims, the British sought to bring the dargah under their control and pocket the considerable donations left by devotees.

To the Ashraf or Muslim elites, their low-class and illiterate brethren who consorted with Hindu devotees were little better than idolaters, and the Muslim clergy had no difficulty in attributing the ignorance of Muslim devotees to their frequent social intercourse with Hindus. The zealots of the Arya Samaj and Hindu revivalists expressed alarm that “their” women were willing to surrender their dignity before a Muslim warrior saint, all too often in the hope of gaining male progeny. Such had been the consummate nature of Muslim dominance that, in Amin’s marvelously elegant and provocative rendering of the revivalist view, Hindus “partaking of holy unction” at “the altars of Muslim saints” were “virtually ingesting the leftovers from their Muslim neighbours’ kitchen.”

Few questions have animated Indian historiography, and discussions in the public sphere, as much as the relations between Hindus and Muslims. Amin’s study is a signal contribution to this literature, and he is particularly enlightening in his suggestion that while we cannot be dismissive of those who have posited a syncretic Indian past, it behooves us to view syncretism not only as a narrative of pluralism and accommodation but also in equal parts as a story of agonism, conflict and clash. His masterful study argues that while our narrative understanding of the Ghazi Miyan saga cannot stop at viewing him as “just a conqueror”, it must also contend with the fabrications and the verisimilitude engendered by local histories, ballads and folklore.

In what Amin calls “the quotidian culture of north India” reside perhaps our best hopes for neutralising those who would seek to homogenise the Indian past in the vain and dangerous quest to create the patriotic and “new Indian national”.

The writer is professor of history, University of California

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home> Lifestyle / by Vinay Lal / October 10th, 2015