Aligarh, UTTAR PRADESH:

Aligarh Muslim University has given the town itself a facelift. Many luminaries have graced the halls of AMU, and it remains an oasis of learning amid uncertainties and controversies that surround the old town

There is something about Aligarh that tells us that the past never dies. It merely reinvents itself to suit contemporary demands. Back in 1937, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, soon to transform into Quaid-e-Azam, took the route with a rare flourish. Recalling the Muslim League session in Lucknow in 1937, author-journalist Mohammed Wajihuddin writes in his persuasively argued, lucidly expressed book, Aligarh Muslim University, “The October 1937 Lucknow session was so important to Jinnah that he discarded his well-cut suits and donned flowing trousers and a long coat. From Mr. Jinnah, he transformed into Janab Jinnah and Quaid-e-Azam. While he had kept himself aloof from ordinary Muslims, now he began mingling with them….He travelled extensively, and Aligarh became a regular place to visit during these travels.” Around the same time, he raised the rhetorical slogan of ‘Islam in danger’ too.

Passing storm(s)

The following year when Jinnah visited AMU, which had begun as the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875, he was given a rousing welcome. The students’ union made him an honorary life member. “It was a tradition the union had followed since 1920, when Mahatma Gandhi was given this membership. In those days they would also put up a portrait of the guests they honoured on the Union Club’s wall. It was such a portrait of Jinnah’s at the AMU Students’ Union Club that created a storm on the campus on May 2, 2018,” writes Wajihuddin.

The storm, essentially a passing one, was caused by local MP Satish Gautam writing to the Vice Chancellor Tariq Mansoor demanding the removal of Jinnah’s portrait from the campus. The demand was not conceded but it made sure the university was in the spotlight, and as a consequence, Aligarh remained in the headlines for days on end. Like it did when the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act protests hit the campus in December 2019. Controversies and Aligarh seem to go together. Yet, AMU, despite frequent protests, occasional violence and various stirs, seems to be an island by itself wherein students seek knowledge, chart out great careers and soak in its culture just as the university’s founder Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, would have advised them. As academic-literary critic Shafey Kidwai, author of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: Reason, Religion and Nation, said, “The question of his (Jinnah’s) glorification does not arise, but the university’s job is to protect the truth of history. His photo was there as the hall carried the names and photographs of all who visited it. The list incudes Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Maulana Azad and Sarojini Naidu.” Unsurprisingly, Prime Minister Narendra Modi called it ‘mini-India’ in an online address.

The story of a name

AMU has the unique distinction of taking along with it the name of the township where it is based, and giving the town itself a facelift. Otherwise, known for its brassware and lock industries, Aligarh has a chequered past, one that has seen many a nawab, maharaja or local leader make an attempt to leave an indelible impression on the town; the most recent one being an attempt by zila panchayat members to rename the place Harigarh. Vijay Singh, zila panchayat chairman, stated, “It was a long-pending demand to rename Aligarh as Harigarh.” He was probably referring to a similar call given in the late 1970s by members of the Jan Sangh, the precursor of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). At that time, a new temple was also called Harigarh Mandir. Nevertheless, the demand to rename the place died down soon enough.

There is an interesting tale behind the name of Aligarh. It was initially called Kol or Koil. Though obscurity surrounds the origin of Kol, according to Edwin Atkinson, who compiled the first gazetteer of the district, the name Kol was given by Balram who slew the great Asura called Kol over here. Noted medieval India historian, Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi, explained the genealogy of the place, at the height of the Harigarh controversy, stating, “Sometime before the Muslim invasion, Kol is said to have been held by the Dor Rajputs. Sultanate period sources, both Persian and non-Persian, mention Kol as a centre for the production of distilled wine. The sources of the period of Alauddin Khalji mention this town as Iqta Kol; Iqta was an administrative unit.” It continued to be called Kol during the Mughal age too with Emperor Jahangir calling it Kol in his memoirs.

However, things changed in the 18th century. The Jats captured the fort briefly and called it Ramgarh, quite removed from the earlier nomenclature of Sabitgarh and Muhammadgarh. Then came the Marathas who dubbed the fort as Aligarh after their governor Najaf Ali Khan. By the 19th century, the town itself came to be called Aligarh. Some locals dispute this fact-based assertion, claiming Aligarh is named after Hazrat Ali, the last caliph and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad.

City of joy

In reality, Aligarh, not Kolkata, was the original City of Joy; it was only in 1985 that Dominique Lapierre called Kolkata the City of Joy. Some 50 years before that, popular Urdu poet Asrar-ul-Haq Majaz had called Aligarh as ‘Shahr-e-Tarab’ or the City of Joy! Moreover, Aligarh, and AMU, whose tarana (anthem) was penned by Majaz, transmits joy.

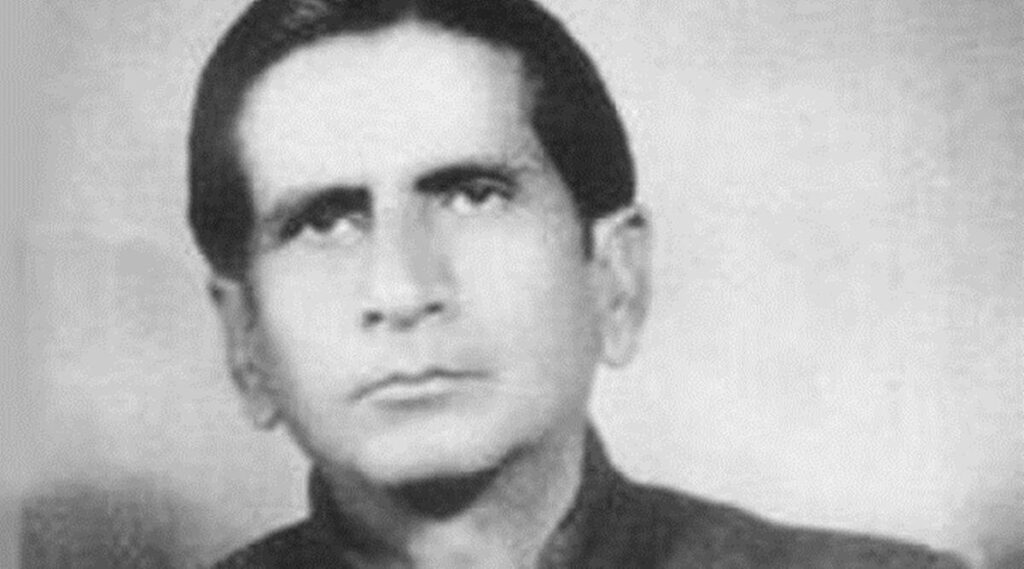

Here studied Begum Para, the heroine of the first talkie Alam Ara. In her painstakingly researched and elegantly produced book, The Allure of Aligarh, Huma Khalil writes, “The musical leanings of Padma Bhushan winner Talat Mahmood…can be traced back to when he used to sing the works of Ghalib and Mir, at the age of 16 in the school functions of Minto Circle. Award-winning film and theatre actor Naseeruddin Shah is still remembered as the finest badminton player of the university.” Not to forget Anubhav Sinha, Surekha Sikri and Zarina Hashmi. Incidentally, Hashmi brought Aligarh to her canvas. A mathematics graduate from AMU, Hashmi had seen villages burning around Aligarh in 1947 and could never forget her home and relatives who were dispersed in the violence.

If violence was here, could prayers have been far behind? Not quite. Hence, besides its historic mosque where countless students stand in neat rows for prayers, Aligarh has the age-old Khereshwar temple which, Khalil tells us, “is the oldest Shiva temple”. Tansen’s guru, Swami Haridas, lived here and Mughal emperors are said to have come down to the temple “to witness the magic of raga Malhaar”.

The persistence of knowledge

Of course, Aligarh has been a happy host to the annual numaish (exhibition) and for years its students frequented Tasveer Mahal, one of a dozen cinema halls in the city. Tasveer Mahal was more than a cinema. It was like a gateway to the University, a rendezvous point for students in the evening. It’s all gone now. What remains untouched is the determination of the students to learn. As Khalil recounts in her book, “Ilm (knowledge) is the second most used word in the Quran after Allah; Aligarh’s motto captures this ethos, ‘(Allah) taught man what he knew not’.” As youngsters seek to know more and more, Aligarh is like the body and AMU its soul.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books / by Zia Us Salam / February 09th, 2023