INDIA :

Babur was a sensitive memoirist with the rare ability to distance himself from his writing

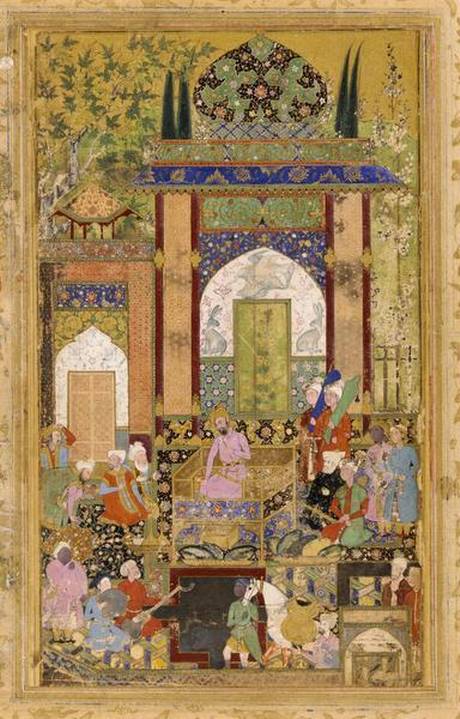

Babur’s memoir did not have a name but is referred to as Baburnama or Tuzuk-e-Baburi. It is the first autobiography from the subcontinent and one of the first in the world. Babur came from two different cultures, of which one was literate and aspired to high culture. This was his father’s ancestral family, which was Timurid. His mother came from the nomadic Mongols, who weren’t literate. Babur describes his maternal uncles in his memoir.

The Timurids had a tradition of poetry, hawking, music, and, of course, war. Babur was from a family of minor nobles who had inherited the governorship of Ferghana. His autobiography begins with a description of the geography and tells us that his father, Umar Shaikh Mirza, died in an accident when he was 39 and Babur 12. The young Babur struggled to hold on to his inheritance, losing several battles, including one in Ferghana, which he had to give up to the victor.

Babur describes these decades of his life in an unemotional and direct way: he hardly valorises his own achievements. Like the great Caesar, whose books on his wars in Gaul and against Pompey may as well have been written by a non-partisan observer, Babur has the ability to distance himself from his life.

Keen naturalist

Babur’s life turns when he is found to be the only living heir to the throne of Kabul. He takes it and turns his eyes to India. For 20 years, he campaigns against India, being held back at the borders each time.

Then, as we know, he defeated the Lodi dynasty (introducing firearms to the subcontinent for the first time) and captured north India in 1526 after a decisive battle at Panipat. Babur died four years later, spending much of this time travelling across India and writing his memoir in the afternoons.

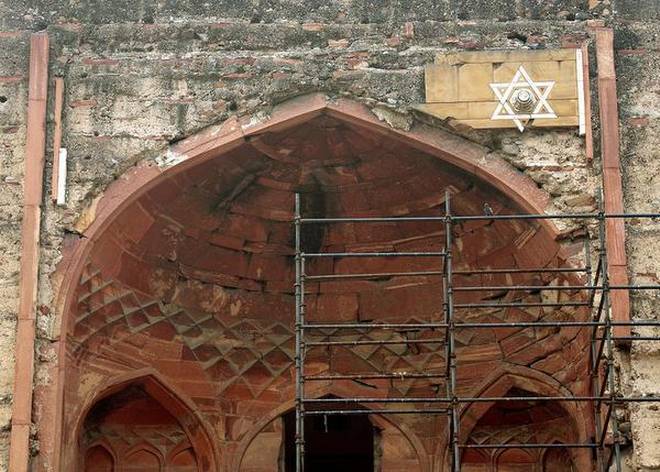

These paragraphs show how much of a keen naturalist he was. “The elephant, which the Hindustanis call hathi, is one of the wild animals peculiar to Hindustan. It inhabits the western borders of the Kalpi country… the elephant is an immense animal and very sagacious. If people speak to it, it understands. If they command anything from it, it does it. Its value is according to its size — the larger it is, the higher the price. On some islands an elephant is rumoured to be as tall as 20 or 30 feet, but here it is not more than 10 feet. It eats and drinks entirely with its trunk. If it loses the trunk, it cannot live. It has two great teeth (tusks) in its upper jaw, one on each side of the trunk. By setting these against trees and walls, it is able to bring them down; with these it fights and does whatever hard tasks fall to it. These teeth are called ivory and are highly valued by Hindustanis.’

‘Like a goat, the elephant has no skin hair. It is relied on to accompany every troop of their armies. It crosses rivers with great ease, carrying a mass of baggage, and three or four can drag without trouble a special piece of artillery that takes four or five hundred men to haul. But its stomach is large. One elephant eats as much as a dozen camels.

Elegant and clean

Babur’s book was not freely available till a British amateur linguist named Annette Susannah Beveridge translated it. She taught herself the particular version of Turkish that Babur wrote in (later Mughals wrote in Farsi) and published it in four volumes from 1912 to 1922.

At the time of the first British census a century and a quarter ago, India was 4% literate. Most Indians even today don’t have four generations of literacy: in fact, the proportion of those of us who can claim to have had great-grandparents who could write is tiny. Babur came from a tradition that already had centuries of literacy.

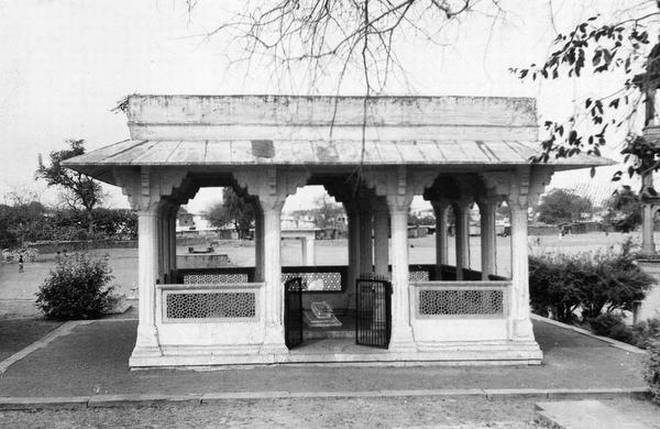

His is elegant and clean writing of the sort that one would expect from a very literate and sensitive person. Babur’s daughter, Gulbadan Begum, sister of Humayun and aunt of Akbar, also wrote a lovely memoir in which she describes her father’s attention to detail which he passed on to his family.

These two works, along with Jahangir’s autobiography, are some of the best material available on the Mughals. It’s a shame that these books are not taught in India’s schools today.

Aakar Patel is a columnist and translator of Urdu and Gujarati non-fiction works.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books – Leather Bound / by Aakar Patel / January 16th, 2020