BRITISH INDIA :

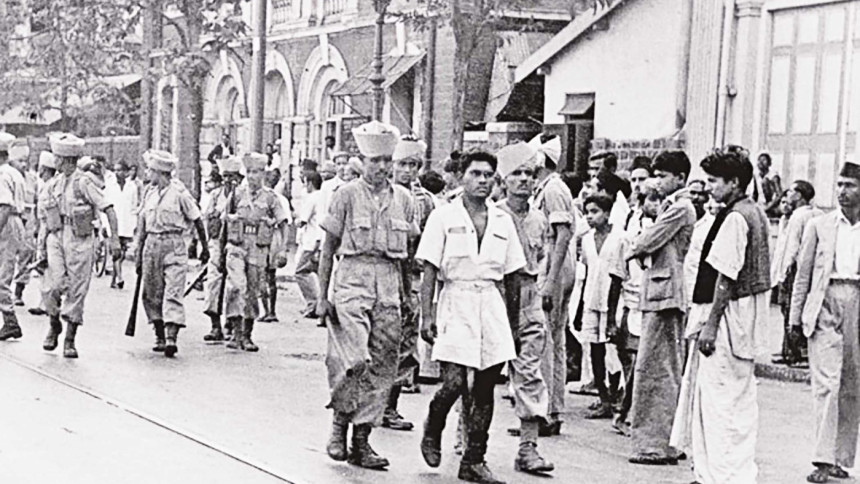

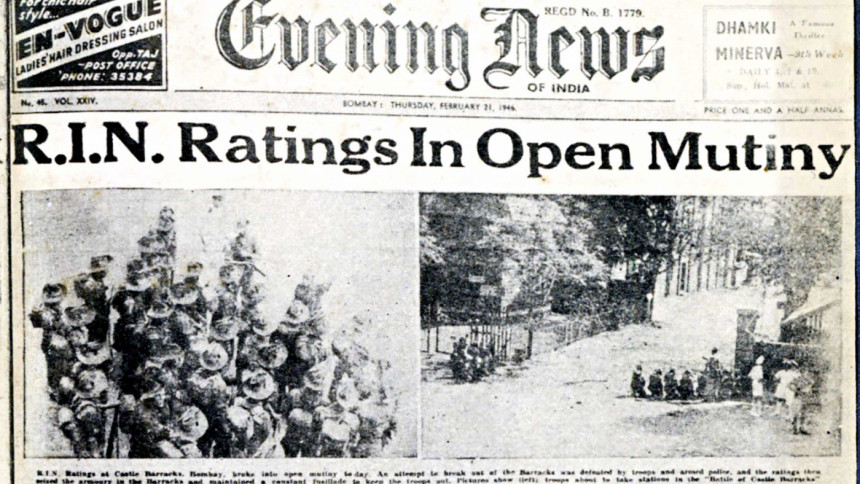

One of the most important but undervalued events of India’s independence movement was the naval revolt of 1946, about which Indian historian Sumit Sarker wrote, “Had this insurrection succeeded, India’s struggle for freedom might have taken a different turn.” From February 18 to 23 that year, more than 20,000 ordinary sailors, known as ratings, and low-ranking officers of 74 warships and 20 installations took part in a strike, which was termed as a mutiny or rebellion.

After Bengal lost its independence at Palashi’s Mango grove in 1757, the British Raj in India faced two major armed revolts: the first one was exactly after one hundred years, the military revolt of 1857, and the second one was 189 years later, the naval mutiny. Both in 1757 and 1857, the freedom fighters were defeated by the arms and tactics of the British rulers, but the naval mutiny failed because of the politicians in India then. It was not only the ratings’ mutiny that the political leadership had decided not to support – the civilian uprising triggered by the naval mutiny, too, was condemned by them. The scale of the civilian uprising, if it happened in a post-colonial era, would have created a revolution or at least caused the fall of the government of the day.

Three days after the mutiny ended and the civilian uprising was crushed with brutal force, the then British Prime Minister Clement Atlee told the House of Commons on February 26, 1946, “I regret to inform the House that grievous loss of life, injury and destruction of property have resulted from all these disturbances. In Bombay, there have been 223 deaths and 1,037 persons have been injured. The total damage includes the looting or destruction of nine banks, 32 government grain and cloth shops which the public can ill-afford to lose, 30 other shops, 10 post offices, 10 police stations and 1,200 street lamps. The number of vehicles destroyed is not yet estimated. In Karachi, there have been seven deaths and 21 cases of injury. In Madras, up to last night, one person has been killed and another seriously injured” (Source: Hansard).

Mr Atlee in his statement said, “Both Congress and Muslim League leaders cooperated in condemning and attempting to stop the disturbances, but the Communist Party issued a manifesto at midnight on Thursday thanking the public for its support.” It perhaps explains why, to this day, the political classes of the three countries born from the partition of India are not willing to admit their failure and give those mutineers and civilian martyrs their due credit. Therefore, in 2021, there was no big event in the subcontinent to mark the 75th anniversary of the naval revolt.

On a personal level, it’s ironic that, despite studying history at the country’s two top universities, I, too, did not take much interest in it during my student life. When I first heard of the rebellion from a mutineer, I had already taken a job and started my professional journey devoid of in-depth history. The mutineer I am talking about was my father, who spoke about his role and feelings about the lost cause during one of my short home visits. My father, Mohammad Dewan Ali Nazir (Royal Indian Navy, RIN, Index no: 34499) was one of the last 3,500 sailors and 300 sepoys who refused to surrender until the last on board of HMIS Akbar.

They were detained after surrendering and were released in August of that year. The mediation and the assurances given by the leaders of both Congress and Muslim League turned out to be nothing but betrayal. Though the uprising was a challenge to the Empire, shaking up the British imperial order, the leaders of the nationalist movement waiting to form an interim government through negotiations were not ready to derail that prospect.

The leaders of the Congress and the Muslim League did not want a revolution – they wanted a peaceful transfer of power. Among the leading politicians, only Congress leader Aruna Asaf Ali extended her support to the ratings’ strike and tried to persuade her party leaders to take a stand in favour of the strikers, but failed in the face of opposition from Vallabhbhai Patel. On February 22, Vallabhbhai Patel sent a message to the rebels to surrender. Only the Communist Party of India came forward in support of the naval revolt and called a general strike. Reading the memoir of one of the key figures of the revolt, Balai Chand Dutt (BC Dutt), and a few other publications, one can easily imagine how much frustration and pain those mutineers felt because of the national leaders’ silence, which they saw as a betrayal. Perhaps it explains why my father, too, lost interest in politics and didn’t speak much about the heroic uprising that ended in a tragedy.

Those nationalist leaders, including Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, advised them “not to mix up ‘political demands along with service demands’; to ‘remain calm’ and to formulate to the naval authorities their service demands.”

But from the very beginning, those naval ratings were raising political demands – particularly, the Quit India slogan.

Their Charter of Demands asked for: 1. Release of all Indian political prisoners; 2. Release of all Indian National Army personnel unconditionally; 3. Withdrawal of all Indian troops from Indonesia and Egypt; 4. British nationals to leave India; 5. Actions against the commanding officer and signal bosonshead for rough treatment of the crew; 6. Release of all detainees (naval ratings); 7. Speedy demobilisation of the RIN ratings and officers; 8. Equal status with the British navy regarding pay, family allowances and other facilities; 9. Best class of Indian food; 10. No return of clothing kit after discharge from service; 11. Better treatment from officers to subordinates; and 12. Installation of Indian officers and supervisors. (Source: Meanings of Failed Action: A reassessment of the 1946 Royal Indian Navy uprising by Dr Valentina Vitali, University of East London, UK.)

Autobiographies of two rebels – BC Dutt and Biswanath Bose – suggest that the then (undivided) India could have been a different place if the revolt of that day had succeeded. The rise of communal politics, the division and instability that is spreading in the states and society, would not have happened.

BC Dutt was one of the organisers of the HMIS Talwar, the ship where the mutiny started. He was arrested and tried for writing a new slogan on a ship on February 1, three weeks before the start of the February 18 mutiny. His book, The Mutiny of the Innocents, contains details of how political literature and pro-independence activities were organised much before their strike.

Biswanath Bose’s RIN Mutiny, 1946 also gives detailed descriptions of how the revolt unfolded. But politicians argued that the revolt was mostly due to the resentment among Indian ratings over low wages, poor quality of food and housing, which was lower than that of the Whites, and racial discrimination.

After the mutiny of 1857, the British rulers banned the entry and discussion of political leaflets in all forces, but BC Dutt used to secretly discuss political documents in the ship HMIS Talwar. Two months before the mutiny, on the Naval Day on December 1, when it was open for public visit, they wrote various slogans, including “Quit India” and “Jai Hind” on the ship. Explaining the reason why the mutiny failed, BC Dutt wrote that while all Europeans and Indians were stunned by the course of events and wondering if it was a revolt, unfortunately the political parties had nothing to say. When it was time to lower the British Union Jack and fly the Indian flag, they felt unprepared.

On February 22, 1946, when the nationalist leaders were busy arranging the ratings’ surrender, Prime Minister Clement Attlee told the parliament that the sailors had given political slogans and demanded that a political leader be given a chance to speak. He also said in the statement that Congress had nothing to do with the insurgency, but the communists and leftists could try to exploit sympathy.

William Richardson, a British researcher, writes in The Society for Nautical Research that the political movement for India’s independence was at the root of the revolt (The Mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy at Bombay in February 1946, May 1993).

Author of the book 1946: The Unknown Mutiny, Promod Kapoor wrote that the navies fell between the two aspirations of the two rulers. One side wanted their impending departure not to be tarnished by the stigma of rebellion. On the other hand, when power was imminent, the other rulers were anxious to see if there were any signs of chaos in the armed forces. Because in the future, they would have to manage these forces.

Politicians assured that no one would be punished, no compensation would be paid, and steps would be taken to meet the demands. In reality, the opposite had happened. Rebel leaders were arrested, tried and punished. Other rebels were told to grab third-class train tickets to return home and to never return to Bombay again. Showing various excuses, deductions were made from salary arrears even for minor damages in their uniforms.

Biswanath Bose’s book gives a glimpse of how frustrated and angry these rebels became with the behaviour of the government and the breach of promises by the political leaders. He wrote, “If patriotism is a crime, then we must be criminals.” Expressing his frustration for not being reemployed in the Indian Navy, he wrote a letter to Prime Minister Nehru asking if there was any law banning his return to the force due to dismissal for taking part in the freedom movement, and how, as a leader of the Congress, Nehru could be the prime minister.

Nationalist leaders were so reluctant to give the mutineers their due credit, that the Indian government banned the Bangla play Kallol (Sound of the Wave), based on the mutiny, by playwright Utpal Dutt, and he was imprisoned. The play was first performed in 1965 in Calcutta at the Minerva Theatre and it drew large crowds.

At the beginning of the naval strike, a Central Strike Committee (NCSC) was formed by the representatives of the ships stationed in Bombay. The committee renamed the Royal Indian Navy as The Indian National Navy. The committee was chaired by Signalman MS Khan, and Madan Singh was the vice-president. One remarkable element of the naval rebellion was the unity of various faiths among both the naval force and the civilians who took to the street. They raised slogans “Hindu-Muslim unite” and “Inquilab Zindabad” on the streets of Bombay.

BC Dutt’s book also speaks of this communal harmony. He wrote, “We are from different regions, and from families of Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Buddhist, but after spending years in the Navy, we sailors have become Indians. The irony is that the politics of communal division and hatred is now intensifying across the subcontinent.

(After leaving the job of a naval instructor, my father joined the office of Indian Civil Supply, and after a short stay in Kolkata, he was transferred to East Bengal. He retired as a magistrate and died on August 29, 2001.)

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist and writes from London, UK. His Twitter handle is @ahmedka1

source: http://www.thedailystar.net / The Daily Star / Home> In Focus / by Kamal Ahmed / July 25th, 2022