INDIA:

A few days ago, when President Ram Nath Kovind presented Padma Awards, the Social Media went abuzz with claims that the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has transformed an earlier elite award into a people’s award. Awardees like Tulsi Gowda, Mohammad Sharif, Bhuri Bai, and others represent those who had worked at the grass-root level. Earlier the award was mostly given to a select band of people who had access to corridors of power in Lutyen’s Delhi; many deserving Indians were ignored.

The optics of Padma awards and the chatter around it made me look into the veracity of these claims. As an Indian Muslim, my primary interest was to understand that how Muslims are represented at the Padma Awards over the year and if there was a change in the attitude of the givers of the awards. The first Padma Awards were presented in 1954. So far, 4,827 persons have been conferred the awards. Muslims are under-represented in these awards. With a population share of around 14%, only 7.5% of the awardees were Muslims, including some foreigners. However, the list of awardees for the years 2020 and 2021 that were conferred on recently, Muslims had all the time higher share. The two lists had 24 of the 260 Padma Awardees who are Muslims, 9.23%.

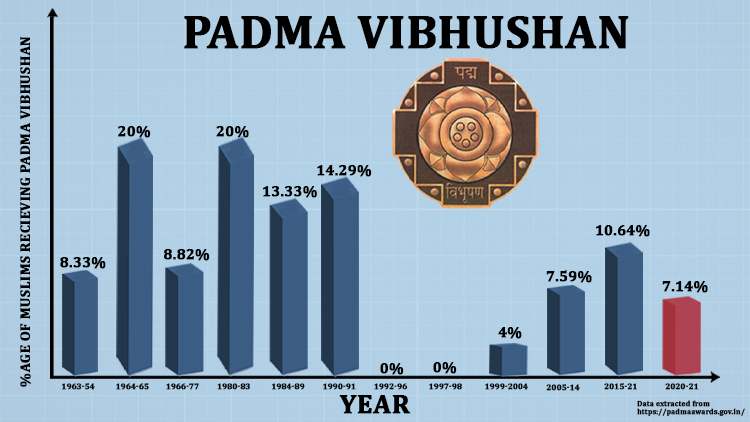

Padma Vibhushan

Coming to Padma Awards, the second-highest civilian honour after Bharat Ratna, that and is awarded for exceptional and distinguished services, I worked with figures of Muslims over the years since 1954. So far 321 people have been bestowed upon Padma Vibhushan. If we look at different regimes, it’s interesting to note that Muslims fared worse during the PV Narasimha Rao-led Congress government and Janata Dal governments of 1997 – 98. During these six years, out of a total of 14 Padma Vibhushan, no Muslim name figured in the list of the prestigious awardees. Interestingly, only 2 Muslims receive the award in 9 years of Jawaharlal Nehru’s premiership. One of them was Zakir Husain, who was later awarded a Bharat Ratna as well. Indira Gandhi oversaw 14 Padma award ceremonies during her two spells as Prime Minister and in this period, 7 Muslims were among a total of 73 honoured. Ten years of Manmohan Singh-led UPA government witnessed 6 Muslims receiving the award, while 5 Muslims received it in seven years of the Narendra Modi-led BJP government. Considering a category of PMs who completed a full term, 13.33% of Padma Vibhushan were awarded to Muslims during the Rajiv Gandhi era followed by Narendra Modi, in whose times 10.64% of the awards went to Muslims.

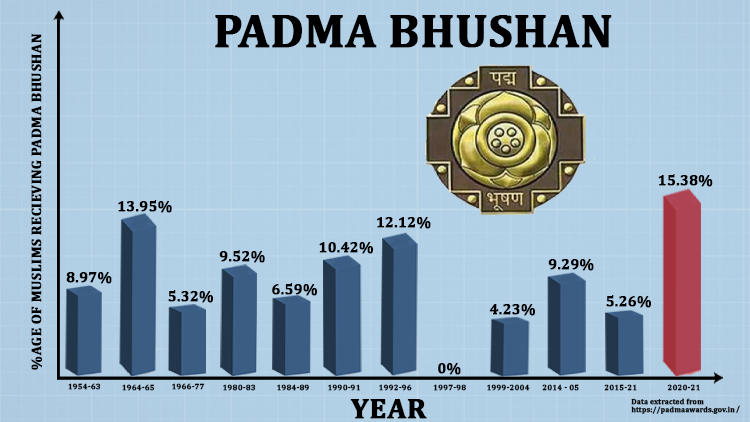

Padma Bhushan

Padma Bhushan is awarded for distinguished service of higher order. To date, 1281, including 95 Muslims, people have received this award. This is at 7.42%, not commiserating with their population. Like Padma Vidhushan, no Muslim was awarded Padma Bhushan in 1997 and 1998. During Nehru’s time (1954-63) 14 Muslims of the total 156 received the award. The Muslim show was very dismal in the first five years of the present regime with one award for the community. However, in the last two editions, we saw 4 Muslims being awarded Padma Bhushan. Of 26 awardees in the two years, 15.38% were Muslims.

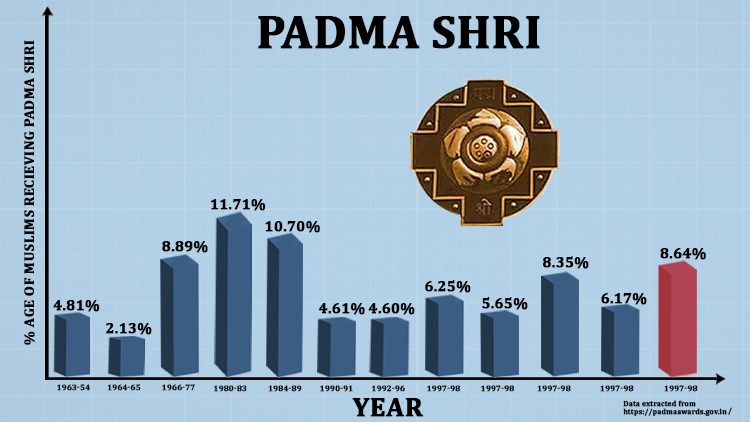

Padma Shri

Padma Shri, awarded for distinguished service has since been conferred on 3,225 Persons. In the first 9 editions, only 9 Muslims were among 187 recipients. A period from 1966 to 1983, saw increased representation when 62 (out of 775), awardees were Muslims (9.29%). In the next five years, 23 more Muslims were awarded and it rose to 10.70%. In the 90s, Muslims representation dipped below 5% as fewer Muslims received Padma Shri. In the last two editions, 8.64% of the recipients were Muslims, a very positive surge that creates optimism.

The figures represent only a larger picture. A closer look reveals that a changed nomination policy for Padma Awards is at work. In 2017, the government opened the nominations for the common Indians as against the system of ministers and members of the government forwarding the names and a committee headed by the PM finalising the list of awardees. The government’s social media campaigns encouraged the people to nominate genuinely deserving and unsung heroes. Earlier, the system encouraged the well-connected people with links to the corridors of power to be nominated and get awarded.

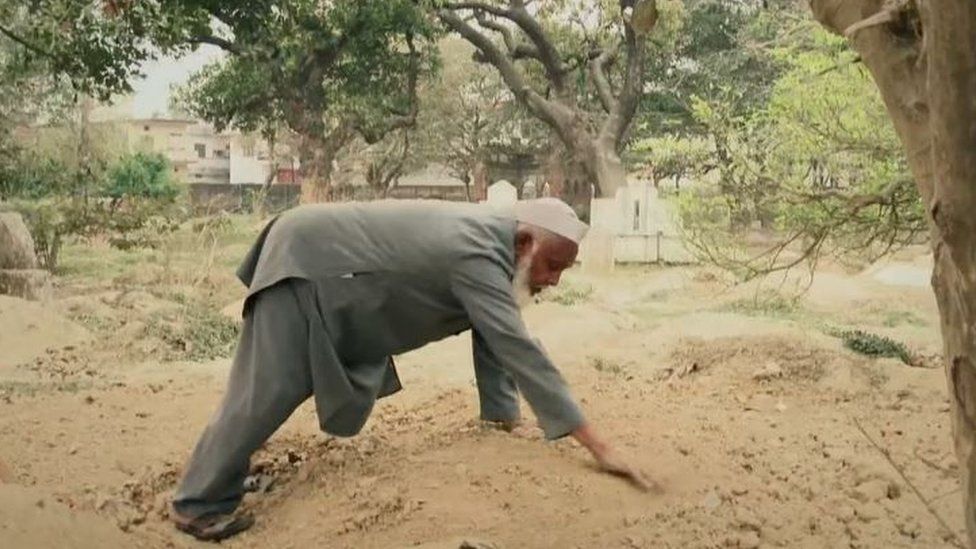

In the new policy, people working at the grassroots are being nominated by the common man. As a result, we see people like Ali Manikfan, Abdul Ghafur Khatri, Mohammad Sharif, and Shahabuddin Rathod receiving the Padma awards. Apart from the fact that there is a positive surge in Muslim representation in these awards, the awards have grown to be more inclusive. Muslims from lower castes, backward regions, and non-elite backgrounds are being honoured. Larger participation of communities and people living at the margins, on social media has ensured that people working among them, and from them, are recognized.

(Saquib Salim is a Writer and a Historian)

source: http://www.awazthevoice.in / Awaz, The Voice / Home> Stories / by Saquib Salim / February 2022