TAMIL NADU / NEW ZEALAND:

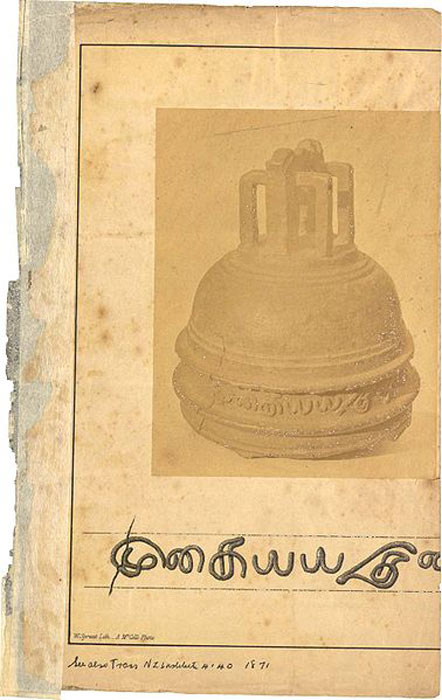

It was 1836 when William Celenso, a Christian missionary from Cornwall in England, first stumbled upon the mysterious Tamil Bell in a remote Maori village in New Zealand. It was being used as a cooking pot by some of the local people, who told the fluent Maori speaker that it had been found under the roots of a large tree, swept up from the ground by a storm many years prior.

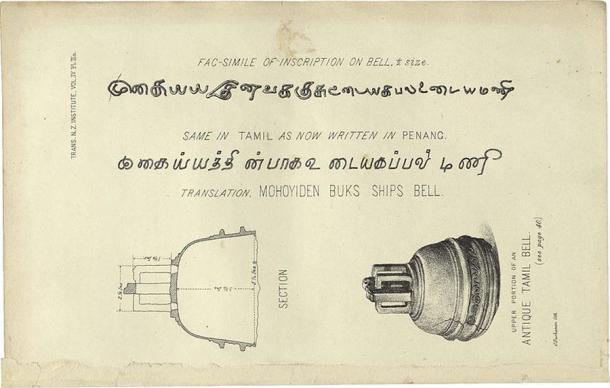

Upon inspection, Celenso discovered a series of markings and runes in an unfamiliar language. Realizing the strangeness of the find, he traded it for a cooking pot, and deposited the curiosity in the Otago Museum in Dunedin. It was later bequeathed to the Dominion Museum, which today is the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington.

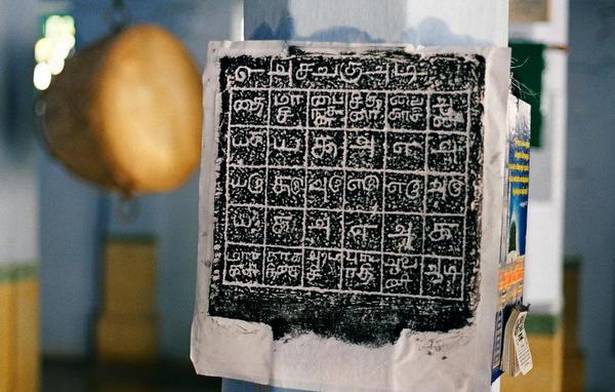

Deciphering the Strange Inscriptions on New Zealand’s Tamil Bell

In 1870, ethnographer J. T. Thompson chanced upon the bell, and puzzled by the strange archaic writing, he took photos and sent them all around India in the hope of producing a translation. Just two months later, Thompson had replies from Ceylon, which is modern-day Sri Lanka, and Penang, a settlement on the Malaysian Straits.

The obscure inscriptions had been identified as ancient Tamil, a language that hadn’t been in use for hundreds of years. The primitive words that adorned the curious metal oddity were Mohoyideen Buks , which were translated to mean “Bell of the Ship of Mohaideen Bakhsh.”

This led to several fascinating revelations. It illustrated that the owner was a Muslim Tamil, of high stature and probably from a famous Indian shipping company based in Nagapattam, in the south-east of India. This was because his name was Arabic, and his first name came from the Tamil phrase meaning “owner of ships.”

Later, in 1940, the age of the Tamil Bell was estimated to be 400 to 500 years old, dating back to the period between 1400 to 1500 AD. This was a remarkable surprise, suggesting that outside contact with New Zealand had been made hundreds of years before English captain Thomas Cook landed on the windswept coast of Poverty Bay in 1769. But had it really?

Evidence of a Tamil Colony in New Zealand

Only 7 years later, another perplexing discovery would further mystify the people of New Zealand, leading to a possible explanation for the out-of-place artifact. In 1877, a shipwreck was discovered half-buried in sand between the ports of Raglan and Aotea. It was first assumed to be a modern ship, as the New Zealand coast was renowned for being extremely dangerous and accidents were common. But this was different.

The vessel appeared to be of Asian origin and extremely old. C. G. Hunt noted how the ship was constructed of teak beams that were placed diagonally and secured by wooden screws, strongly suggesting it was built in South East Asia. Inside, a brass plate with Tamil inscriptions and a plank of wood containing the familiar name Mohoyd Buk were found.

- Tamils and Sumerians Among the FIRST to Reach Australia and Antarctica? PART I

- History’s Lost Transoceanic Voyages: Tamils and Sumerians Among the FIRST to Reach Australia and Antarctica?— PART II

Inexplicably both pieces of tantalizing evidence vanished in Auckland, and experts were never able to compare it to the timeworn letters of the Tamil bell. Nevertheless, several early theories were put forward by the historians of the day. Some argued this was proof of an early Tamil colony on New Zealand. Others maintained that the skillful construction and expertise of the Tamil seafarers made it perfectly possible they could have sailed to New Zealand.

On the other hand, the evidence for such arguments remains scarce. As far as historical record is concerned, the eastern-most frontier for Indian sailors was the island of Lombok, next to Bali in current-day Indonesia. Furthermore, the Spice Islands of West New Guinea, where nutmeg, mace, and cloves could be exclusively found, although in use, were never controlled by the Tamils and instead remained in the hands of local magnates of Ternate, Tidore, and Amboyna. Add to this that no other Indian relics have ever been found in New Zealand.

A Lost Portuguese Trading Ship?

Another theory put forward is that the Tamil Bell was originally Portugese, and from a lost ship sent as part of a fleet by the Portuguese emperor to secure the Spice Islands. From the 1490s, the Portugese became a major player in the Indian Ocean trade network, securing Asian goods for a booming demand back in Europe. In 1511 the Portuguese even established a trading colony on the Malacca Straights and in many places on the Indian mainland.

One of these places was Goa, and in 1521 the Portuguese Viceroy sent out a fleet of three caravels captained by Cristovas de Mendonca, to explore the lands beyond the Spice Islands. Only Mendonca’s caravel returned, the other 2 being lost at sea and never seen or heard from ever again.

In 1877, the shipwreck found on the New Zealand coast was identified as being constructed in Goa, precisely where the Portuguese ships had set out from. Tamil was widely spoken in Goa which neatly explained the Tamil writing on the bell.

However, all of this is incredibly unlikely. There is no direct evidence that points to a bell being on the Portuguese caraval. Lastly, the Portuguese had already established an incredibly lucrative trade system, which meant there was no motive for them to explore further as the known world of the Indian Ocean was already providing them sufficiently.

Spanish Castaways or Anthropological Science Fiction

One of the most famous and controversial theories was advanced by Robert Langdon in his book The Lost Caravel , in which he proclaimed that the Tamil Bell was brought to New Zealand by a group of Spanish sailors from the East Indies who became disorientated and eventually settled in New Zealand, hundreds of years before Thomas Cook’s arrival.

He wrote that in 1524 the King of Spain ordered an expedition to the Spice Islands, sending a sortie of six ships. A maelstrom of disasters ensued, with two wrecked on the coasts of Patagonia and the Philippines, one reaching Mexico, another returning to Spain, and the remaining two disappearing. One of the stray caravels, the San Lesmes, which contained the Tamil Bell, was last observed in 1526, voyaging across the Pacific Sea.

After running aground at Amanu, an atoll of French Polynesia, where four cannons were later discovered, the crew repaired their ships and sailed on to the atolls of Ana and Raiatea, where several of them settled down and married the native woman. Later on, in a bid to return to Spain, the weary seamen set out west, discovering New Zealand in the process and deciding to make a home on its verdant shores.

The descendants of the castaways explored further, discovering new lands as far as Easter Island, and introduced new cultures, customs, and languages to the Polynesian people influenced by their Basque origins. Langdon was convinced that the additional discovery of a Spanish helmet dated from the 16th century in Wellington Harbor in the 1880s gave his hypothesis more credibility.

However, like the Tamil and Portuguese ship propositions, Langdon’s argument has been highly criticized for its extravagant interpretation of available evidence. Bengt Danielsson, an academic from French Polynesia, described it as “anthropological science fiction.” Throughout his account, Langdon disregarded all existing archaeological and historical literature of the Pacific which often contradicts and disproves his ideas.

The existence of Caucasian-like individuals with fair-skin, red hair, and blue eyes on many Pacific Islands was deemed proof of his hypothesis. While there is no doubt that these traits existed, even in the earliest contact with Polynesian natives, Langdon argued the Spanish castaways were the only source of these genetics, a fact that is impossible given that there were only reportedly 20 to 50 castaways in the forgotten band. It was equally as unlikely that they had travelled to all of the Polynesian Islands .

Next, Langdon pointed to linguistic anomalies as a sign that Spanish words were absorbed into the local dialects. However, there are no identifiable Spanish words in the languages of Eastern Polynesians. Without a shred of evidence, Langdon explained that this was because the children only learned the language of their mothers, leading to the decline and eventual disappearance of the Spanish, Basque, and Galician languages of the fathers. He even proposed that the lack of sounds in the Polynesian tongue meant that Spanish words could easily have been changed beyond recognition after only a day or two.

On the other hand, in all other cases of European and native intermixture in Polynesia, European languages were adapted into the local speech. A diverse array of English words still remain in Polynesian languages today after being incorporated 200 years ago. For example, on the Pitcairn Islands, where only one Englishman lived with eight native women, his descendants still speak English!

In addition, Langdon believed that the indigenous beliefs of Polynesians were derived from the Christian faith of the Spanish diaspora. He utilized sources from 1874 from Catholic missionary Albert Montiton, who remarked on how Christian the native religion seemed to him. Yet Langdon completely ignored the wide conversion of natives to Christianity that happened from 1817 onwards, which presents a more reasonable explanation.

Finally, Langdon cited the “talking boards” of Easter Island, a series of stone tablets discovered in the 1860s with archaic runes, as a type of script invented by the Spanish castaways. Yet his main source for this point was a native guru called Hapai, a man who claimed that Europeans had inhabited Easter Island, and whose evidence was subsequently found out to be fabricated. In the end, Langdon’s farfetched argument was systematically disproven, and the confusion over the Tamil Bell persisted.

The Derelict Theory: Did the Tamil Ship Drift to New Zealand?

After years of fantastical hypothesizes, Brett Hilder entered the debate with a theory more rooted in reality. His so-called derelict theory re-invigorated the earlier claim that the bell came from a Tamil ship. Hilder’s theory attacked the assumption prevalent in most theories that the crew who possessed the Tamil bell were alive. In the choppy, capricious oceans, there had been many instances of intact wooden ghost ships being found without any sailors.

The Flying Dutchman was perhaps the most famous example, having been discovered with full sails and without anyone on board. Nearer the Pacific, the wreck of the sailboat Joyita, on a journey from Apia to the Tokelau Islands, was observed to have no remaining personnel when it was detected half-submerged in the sea.

These “derelicts” were usually still floating, even after many years at sea, because of the buoyancy of their hulls. Hilder entertained the idea that the Tamil Bell originated from a Tamil merchant ship that was caught in the eastward sea current between Antarctica and the southern parts of the continents.

During the late 1400s and 1500s, when the bell was dated, Tamil seafarers dominated the trade networks of the vast Indian Ocean. Muslim Tamils were particularly skilled navigators, plying their wares across the sea as far as the eastern coast of Africa. Indeed, modern examples of the power of the great Southern Current, which stretches from New Zealand to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, cement his idea.

For instance, in June 1973 it was reported in the Nautical Magazine of Glasgow that an unmanned lifeboat had travelled 7,000 miles from the coastline of East London, South Africa, to the Princess Royal Harbor in Albany, Australia. Thirty jars of barley, sugar, and lifeboat biscuits were found in perfect condition, sealed in two compartments. It is more likely, then, that a similar fate befell a Muslim Tamil ship, and that the preservation of its wooden hull helped bring the Tamil Bell to a wild new frontier of the world.

Enduring Enigma of the Tamil Bell

Since its discovery in 1836, most theories surrounding the Tamil Bell were highly speculative and lacked the sufficient evidence to be taken seriously. Unlike others, Brett Hilder’s focus on the Great Southern sea current, a real geographical phenomenon, presented a case for the Tamil Bell that finally made sense without the mental leaps and bounds taken by other theorists such as Langdon, whose sole proof that the crew of the San Lesmes reached Amanu and married the native woman was the fact that four rusty old cannons had been found there.

- The Age of Discovery: A New World Dawns

- 500 Years Ago Today Magellan and Elcano Set Sail to Conquer the World

Yet even Hilder’s theory has weaknesses. All of the theories incorporated the 1877 shipwreck as a key piece of evidence that identified if the bell was brought by the Tamils, Portuguese, or Spanish. Yet by 1890 the shipwreck, said to be half-sunken in the sand, had mysteriously disappeared, never to be seen again. Subsequent attempts to re-find the wreck, as late as 1975, were all unsuccessful.

“The problem with all these and other ‘mystery’ items, such as ancient shipwrecks on New Zealand’s wild west coast beaches that are reputed to be uncovered briefly in storms, is that in the absence of hard evidence to explain their existence and context, numerous fanciful interpretations are often placed upon them according to particular agendas,” explained Katherine Howe, summing up the situation perfectly. Thus, the mystery of the Tamil Bell lives on.

Top image: Representational image of a tamil bell from inside of Meenakshi Hindu temple in Tamil Nadu, South India. Source: Владимир Журавлёв / Adobe Stock

By Jake Leigh-Howarth

Danielsson, B. 1977. “The Lost Caravel by Robert Langdon” in The Journal of the Polynesian Society , 86:1.

Dokras, U. 2021. “Marco Polos of Ancient Trade – The Tamilians” in Academia. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/53267513/Marco_Polos_of_Ancient_Trade_The_Tamilians

Hilder, B. 1974. “The story of the Tamil bell” in The Journal of the Polynesian Society , 84:4.

Howe, K. 2003. The Quest for Origins: Who First Discovered and Settled the Pacific Islands? University of Hawaii Press.

Maddy, 2021. “The Many Mysteries Behind the Tamil Bell. Historic Alleys” in Historic Alleys . Available at: https://historicalleys.blogspot.com/2021/05/the-many-mysteries-behind-tamil-bell.html

O’Conner, T. 2012. “A mystery wreck and a ship’s bell” in Waikato Times . Available at: https://www.pressreader.com/new-zealand/waikato-times/20120730/281968899818555

source: http://www.ancient-origins.net / Ancient Origins / Home> News / by Jake Leigh-Howarth / March 13th, 2022