Nagapattinam, TAMIL NADU :

Cutting across faiths, sailors pray to Nagore Miran for a safe journey

“There are so many boats named after ‘Nagore Andavar’ in Kasimedu (a fishing harbour in Chennai). Don’t hastily jump to the conclusion those are owned by Muslims. They actually belong to our people,” cautions Manoharan, to me and writer Nivedita Louis. We were at his residence to record songs on Nagore Andavar as sung by Manoharan, aged about 80 and a retired fisherman of Olcott Kuppam in Chennai. Though the Nagore Andavar he refers to is a 16th century Muslim Sufi saint who transcended religious divides, it still comes as a surprise to know that Hindu fishermen living some 300 km north of Nagore where the Sufi lies buried, name their boats after him.

Continues Manoharan, “When the sea gets turbulent and we feel our lives are at risk, it is to Nagore Andavar that we plead, through songs to rescue us. And miraculously the winds will change, push us to the safety of the shore,” he says. He immediately breaks into a song in Tamil that pours out their fears and pleads for their safety from the wrath of the sea. A hundred km away from Chennai, fishermen at Veerampattinam of Pondicherry, praying for their safety before sailing into the rough sea, make their offerings to Nagore Andavar at Nagoorar Thottam.

Interestingly it was not just fishermen of the Tamil coast, but anyone who left the Tamil coastline in the 19th century placed their faith in the saint to safely cross the seas, and wherever they landed, they built a memorial or shrine for him. Those shrines today stand as testimony to the path taken by the Tamil Diaspora across continents, from maritime traders to indentured labourers. From Penang in South East Asia to the Caribbean in the Americas, with recent additions in Toronto and New York, the influence of Nagore Miran as the Sufi is also known, can be seen.

Nagore Miran, the 16th century Muslim Sufi saint, buried, as the name suggests in Nagore in Nagapattinam district of Tamil Nadu was born as Sahul Hameed in Manikhpur in North India. He took to spiritualism early in his life and travelled through West Asia to Mecca and to Burma and on to China before touching Ceylon and the South Indian coast. Travelling through the Tamil country with his band of followers, local lore has it that the Sufi cured an ailing Achutappa Nayak, the ruler of Thanjavur, and a grateful Nayak gifted land for the Sufi to stay at Nagore. Interestingly, the Sufi arrived at at a time when the Indian seafarers, particularly the Tamil Muslim ship owners, were being harassed by powerful Portuguese naval fleets.

With the hostile Portuguese at Nagapattinam, the presence of the Sufi at nearby Nagore was a great solace not just to the harassed maritime traders but to the sea faring fishermen. Among the miracles attributed to him, it was widely believed by the fishermen that, the Sufi, while residing at Nagore was able to plug the hole in a ship which was otherwise sinking off the coast.

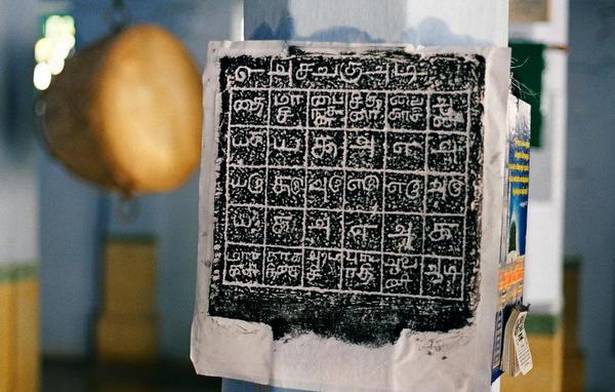

His mysticism touched the lives of people across faiths — from Kings to commoners. They flocked to him and after his death to the Nagore dargah where he lies buried. The dargah received endowments from the Thanjavur Nayaks, Marathas and Nawabs. One of the five minarets at Nagore dargha, the tallest at 131 feet, was built by the Maratha ruler Maharaja Pratap Singh Bhonsle in the mid-eighteenth century. Govindasamy Chetty, Mahadeva Iyer and Palaniyandi Pillai are some of the donors.

In the late 18th century when the British founded Penang in Malaysia as the fourth presidency, it attracted considerable Tamil Muslim traders who were already doing business in South-East Asia. Mostly known as Chulias (those from the land of the Cholas), they became one of the earliest settlers in Penang. By early 19th century, when the settlement had grown considerably, the Company enabled them to build the Kapitan Keling mosque. They built a memorial for Nagore Sahul Hameed at the junction of Chulia street and Kings street. Similar memorials were built across South-East Asia, in Aceh, Burma, Vietnam, Ceylon, Singapore and many other parts of Malaysia wherever the traders went.

However unlike the Tamil Muslim traders, who traded within the Asiatic region, the indentured labourers were taken to distant continents by the colonial rulers, to work in the new plantations. In the early 19th century, as ships set sail from Nagapattinam, the indentured labourers, placed their faith on Nagore Miran for their safe journey across the turbulent seas. The labourers reached lands as distant as the Caribbean Islands. “When in early 20th century they moved to better pastures in Canada and the U.S., Nagore Miran along with Madurai Veeran, Mariamman and many other gods and saints found place in the newly constructed temples at Toronto and New York,” points out Prof. Davesh Soneji of University of Pennsylvania.

If the Muslim traders treated Sahul Hamid as an Awliya, the Hindu indentured labourers, used to idol worship, gave him a form and placed him in the sanctum along with other Hindu deities such as Madurai Veeran, Muneeswaran and Mariamman. “…this divinity is an integral part of most of the ‘Madrassi’ or South Indian Hindu temples in this region. In French Caribbean Islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, Nagore Mira is worshipped in the form of a Boat and mast decorated with colourful flags. 786, the sacred Islamic number, can be found engraved on the boat,” writes Suresh Pillai, an interdisciplinary artist working at the intersection of arts, archaeology, and cultural artefacts to locate material history and empirical knowledge among living cultures.

Interestingly in Tamil Nadu itself, every year, at the beginning of the Kandhurior Urs festival in honour of the saint, festooned boats resembling ships, adorned with various flags, navigate their way through the streets of the old harbour town of Nagapattinam, before cruising through the national highway leading to Nagore. “It is really surprising how these big boats squeeze themselves through the narrow streets of Nagapattinam and Nagore before finally halting at the saints abode. After which the flags are raised on different minarets of the dargah on the first day of the Urs,” says Harini Kumar, a research scholar on Tamil Islam. Typical of the syncretic nature of the Sufi shrines, as the festival gathers momentum, various communities pay their respects to the saint, with specific non-Muslim families, including the fishermen, accorded hereditary honours.

While the syncretic nature is a common thread that runs through the Sufi beliefs, it is Nagore Miran the Sufi, emerging as the patron saint of the seas, enabling us to trace the path taken centuries ago by the Tamil Diaspora, that seems unique.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture / by Anwar’s Trails / by Kombai S. Anwar / March 07th, 2019