INDIA :

New Delhi, (IANS) :

Stories of conviction and contribution of Indian Muslim women, who “gave up the purdah” and were at “the forefront of the nationalist and feminist discourse” in the past century are on display here.

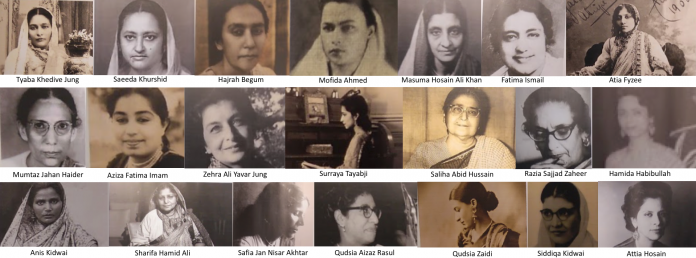

The exhibition on 21 “pathbreakers” opened for public view on Saturday.

Organised by Muslim Women’s Forum at the India International Centre (IIC), the show “Pathbreakers: The Twentieth Century Muslim Women of India” features women who remain largely unheard of and unsung in the mainstream narrative.

During and after the freedom movement, a note on the exhibition said, many Muslim women shed the ‘purdah’ and became partners in the project to build a new India.

They went on to become writers, teachers, artists, scientists, lawyers, educators, political workers, trade unions, MPs, and MLAs.

“With a few exceptions, most of them have been forgotten in time.”

The show, inaugurated by author-filmmaker Syeda Imam (granddaughter of early 20th century writer-educator Tyaba Khedive Jung), embodies the spirit of the active contribution of these women, and as Imam said, “were not in the recesses of home and kitchen”.

Far from the commonly-held impression of silenced, cloistered and acquiescent women, ‘Pathbreakers’ narrates the stories of strong, determined and engaged women, the note said.

Some of these women include Qudsia Aizaz Rasul, the only Muslim woman member of the Constituent Assembly and author of “From Purdah to Parliament: A Muslim Woman in Indian Politics”; Assam’s first woman MP Mofida Ahmed, elected from Jorhat in 1957; and Aziza Fatima Imam, who served in the Rajya Sabha for 13 years starting 1973.

Why Muslim women?

The exhibition of photographs, text and video installations, points to their significant contribution towards the building of the nation, along with their sisters of other communities, through its freedom struggle, independence and beyond.

“A multiplicity of stereotypes are constructed by diverse actors regarding Muslim women. But the fact is there is no undifferentiated amass’ of Muslim women. Like women of all socio-cultural groups, they too are a divergent, shifting composition of individuals, often dumped in popular parlance into one single heap. This homogenisation has to be rejected,” the note read.

The show also projects video recordings of readings from writings of some of the featuring women.

The organisers, however, said while the participating women might seem elite, it is only the first step in identifying and recognising pathbreakers from all sections.

Featured are Anis Kidwai, Atiya Fyzee, Atia Hossain, Aziza Imam, Fatima Ishmael, Hamida Habibullah, Hajira Begum, Mofida Ahmed, Masuma Begum, Mumtaz Jahan Haider, Qudsia Aizaz Rasul, Qudsia Zaidi, Razia Sajjad Zaheer, Saleha Abid Hussain, Sharifa Hamid Ali, Saeeda Khurshid, Safia Jan Nisar Akhtar, Siddiqa Kidwai, Surayya Tyabji, Zehra Ali Yavar Jung and Tyaba Khedive Jung.

This exhibition was first held here in May, and was supported by the UN Women. The current show is open till December 8.

source: http://www.twocircles.net / TwoCirlcles.net / Home> Indian News> Indian Muslim / by IANS / December 03rd, 2018