Machreta (Sitapur) – Aligarh, UTTAR PRADESH :

A votary of India’s syncretic culture, the novelist will be remembered for his sketches of Awadh aristocracy and his prose style which has touches of grandeur

‘Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself; I am large, I contain multitudes’, wrote Walt Whitman in his famous “Song of Myself”. Qazi Abdus Sattar (1933-2018), a novelist, a literary polemist and a master raconteur, who died last week after a long illness, contained multitudes in his fiction and conversation. If grand historical figures jostle with ordinary folks in his fiction, in his conversation he used his right to offend to the maximum. His fiction always touched crests and his conversation knew no troughs.

Beautiful metaphors

A proper assessment of a writer begins after his death, more so in the relatively limited circle of Urdu criticism where everyone knows everyone else. However, most critics and readers of Qazi Abdus Sattar credit him for writing remarkable historical novels, for his sketches of Awadh aristocracy, and above all for his prose style which has touches of grandeur. Among his historical novels “Dara Shikoh” (1968) gives an account of the war of succession among Emperor Shah Jahan’s four sons and Dara’s defeat at the hands of Aurangzeb, using beautiful metaphors and turn of phrases. His epic style characterises the novel. A votary of harmony and India’s syncretic culture, Qazi Abdus Sattar’s sympathies with Dara Shikoh are unmistakable. A scholar of Sanskrit texts, his Dara is often dressed in traditional Hindu attire and he prevails upon his father Emperor Shah Jahan to exempt the Hindu devotees from paying tax for taking bath in river Ganges.

Delineating the bard

His novel “Ghalib”(1976) captures not only the vignettes of Ghalib’s life – his devotion to poetry, his economic worries, his travels, his wit, his love life – but also the ethos and the milieu of the 19th Century.

Qazi Abdus Sattar is equally comfortable in delineating characters from distant Islamic history in novels like “Salahuddin Ayubi” (1968) and “Khalid Bin Waleed”. His novel “Salahuddin Ayubi” takes the reader into the 12th century period of the crusades in which Salahuddin Ayubi distinguished himself for his bravery, his excellent detective work and his love of human beings. Paradoxically the novel also shows that oppression of the weak and the marginalized groups has been an ugly fact of history.

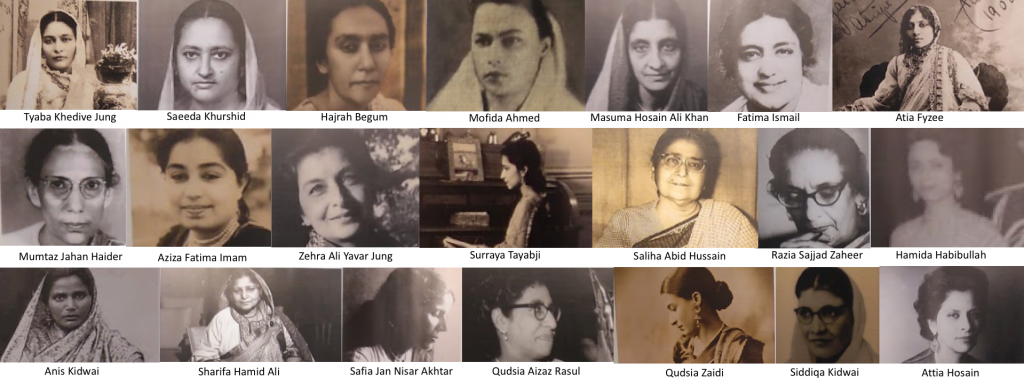

Qazi is both an heir to and critic of landed aristocracy. The taluqdars of Awadh, who are also the concerns of Qurratul Ain Hyder and Attia Hosain, hold some inexplicable fascination for him. They represented a past that he kept living both in his fiction and life. He appeared to welcome the end of Zamindari but he refused to free himself from its sinister charm. He always aligned himself with progressive causes and was a key figure in Janvadi Lekhak Sangh, but he did not see any contradiction in his celebration of the lifestyle associated with an unjust system.

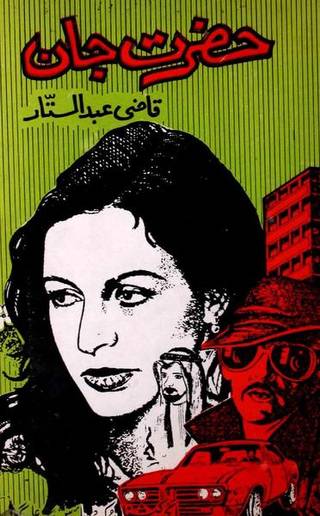

As a fiction writer he is spot on in his treatment of the landed gentry of Awadh. His novel “Shab Guzida”(1966) gives an inside view of the life of zamindars and taluqdars of Awadh. The unjust debauch Bade Sarkar and his virtuous son Jimmy represent different sets of values in the novel. His “Pahla aur Akhiri Khat” (1968) charts a life away from the framework provided by Progressive Writers’ Movement. Through the depiction of the life of Chaudhri Nemat Rasool of Lalpur, the novelist shows zamindars in the grip of economic and social problems after the end of Zamindari. “Hazrat Jaan” and “Tajam Sultan” are his other remarkable works. Unlike many other writers in the past who have made Awadh the subject matter of their work, Qazi’s distinction lies in focusing on the rural life in Awadh in his fiction.

He was equally successful in his novelettes and short stories with Awadh again very much providing the backdrop of many of his narratives. “Peetal ka Ghanta” , a collection of his short fiction, includes ‘Peetal ka Ghanta’, ‘Malkin’, ‘Azu Baji’, and ‘Majju Bhaiya’. “Ghubar-e-Shab”, also set in a village around the period of the Partition, treats the subject of communal disharmony and communal politics with irony.

A Padma Shri awardee, apart from numerous other prestigious awards, Qazi Abdus Sattar worked as professor of Urdu at Aligarh Muslim University and was great friends with scholars and critics of Hindi. He greatly valued his readers in Hindi and stressed the closeness of Hindi and Urdu (even Punjabi). But he was very strongly against changing the script of Urdu. He also strongly believed that literature should be ‘beautiful and wholesome’.

A great fan of Flaubert, he could achieve a lot in very little, thanks to his felicity with language. No wonder he has not written door stoppers and “Ghalib”, all of less than 300 pages, is his longest work.

A raconteur par excellence and not known for mincing his words, he was an interviewer’s dream and an event manager’s guarantee for the success of a literary gathering. Prem Kumar’s remarkable book of his interviews is a blessing for Hindi readers as is Rashid Anwar’s for Urdu readers. Possessed with Oscar Wilde like ability to produce witty (often gossipy) quotes, Qazi Abdus Sattar’s sentences, as Urdu poet Shahryar once said, drew the applause generally reserved for Urdu poets.

The grace and grandeur of his prose style rubbed off on his life. Tariq Chatari, a prominent Urdu short story writer, who believes that Qazi took Urdu afsana to a different level, says that he carried himself very much like a character from his fiction. Qazi Afzal Husain (no relative) considers Qazi a master prose stylist in line with Muhammad Husain Azad and Abul Kalam Azad. Time will tell.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Authors> Obituary / by Mohammad Asin Siddiqui / November 09th, 2018