DELHI :

She was one of the most powerful women of medieval India, a Mughal princess like no other. And yet, her extraordinary story remains lost in the pages of history.

In an unassuming part of India’s capital city, amidst winding alleys lined with attar and chadar sellers, lies the 800-year-old dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya—one of the most revered saints in Sufism. From dusk to dawn, thousands of devotees throng this bustling complex to pay their respects.

Yet, few know that Delhi’s most famous Sufi shrine is also home to the tomb of one of the most powerful women of medieval India, Jahanara Begum.

A writer, poet, painter and the architect of Delhi’s famous Chandni Chowk, Jahanara was a Mughal princess like no other.

This is her story.

The eldest child of Emperor Shah Jahan and his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal, Jahanara was born in Ajmer in 1614. Growing up in one of the richest and most splendid empires in the world, the young princess spent her childhood in opulent palaces, humming with family feuds, battle intrigues, royal bequests and harem politics.

As such, she was well-versed in statecraft by the time she was a teenager.

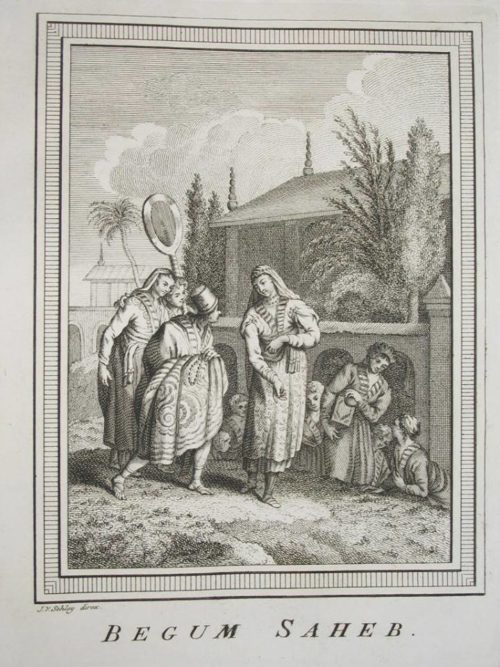

Soon after, Jahanara was appointed Begum Sahib (Princess of Princesses) by her doting parents. She would often spend her evenings playing chess with Shah Jahan, understanding the workings of the royal household, and helping her father plan the reconstruction of other palaces.

As French traveller and physician François Bernier writes in his memoirs, Travels in the Mogul Empire ,

“Shah Jahan reposed unbounded confidence in his favourite child; she watched over his safety, and so cautiously observant, that no dish was permitted to appear upon the royal table which had not been prepared under her superintendence.”

Jahanara was also especially close to Dara Shikoh, Shah Jahan’s eldest son and her favourite brother. The two shared a love of poetry, painting, classic literature and Sufism.

In fact, she also wrote many books, including a biography of Ajmer’s Sufi saint Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, displaying her flair for prose.

But tragedy struck the young princess’s life with the untimely demise of her beloved mother, Mumtaz, in 1631. At the tender age of 17, she was entrusted with the charge of the Imperial Seal and made Malika-e-Hindustan Padshah Begum—the First Lady of the Indian Empire—by the shattered Emperor, whose grief kept him away from his royal duties.

It was only on Jahanara’s behest that the inconsolable Shah Jahan came out of mourning.

In the years to follow, she became her father’s closest confidante and advisor. Highly educated and skilled in diplomatic dealings, her word became so powerful that it could change the fortunes of people. Her favour was much sought-after by foreign emissaries.

In 1654, Shah Jahan attacked Raja Prithvichand of Srinagar. Despairing of success in the battle, the Raja sent a plea for mercy to Jahanara. The Princess asked him to send his son, Medini Singh, as a sign of his loyalty to the Mughal Empire, thereby getting him a pardon from the Emperor.

The following year, when Aurangzeb was the viceroy of the Deccan, he was bent on annexing Golconda, ruled by Abdul Qutb Shah. The Golconda ruler wrote an arzdast(royal request) to the Princess, who intervened on his behalf. Qutb Shah was pardoned by Shah Jahan (against Aurangzeb’s wishes) and secured his safety on payment of tax.

Interestingly, Jahanara was also one of the few Mughal women who owned a ship and traded as an independent entity.

Named ‘Sahibi’ after its owner, Jahanara’s ship would carry the goods made at herkarkhanas (factories) and dock at her very own port in Surat; its revenue and the colossal profits she made via trade significantly boosted her annual income of three million rupees!

In his book Storia Do Mogor, Italian traveller Niccolao Manucci writes, “Jahanara was loved by all, and lived in a state of magnificence.” The book is considered to be one of the most detailed accounts of Shah Jahan’s court.

But Jahanara’s political and economic clout failed to have an impact on the bitter war of succession between her brothers, Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. She made several attempts to mediate between them, but as Ira Mukhoty writes in her book Daughters of The Sun , she had “underestimated the corrosive loathing that Aurangzeb has for Dara, whom he blames for his father’s cold criticism throughout his career”.

Aurangzeb ultimately killed Dara Shikoh and placed an ill Shah Jahan under house arrest in Agra Fort’s Muthamman Burj (Jasmine Tower). Faithful to her father, Jahanara set aside her lucrative trade and luxurious lifestyle to accompany him into imprisonment.

A constant presence beside Shah Jahan in his exile, she took care of him for eight years, till he breathed his last in 1666.

It says much for her stature in the Mughal court that after Shah Jahan’s death, Aurangzeb restored her title of Padshah Begum and gave her a pension along with the new title of Sahibat al-Zamani (Lady of the Age)—befitting for a woman who was ahead of her time.

Unlike other royal Mughal princesses, she was also allowed to live in her own mansion outside the confines of the Agra Fort.

“Jahanara establishes herself in the city as the most influential woman patron[s] of literature and poetry. She collects rare and beautiful book[s], and her library is peerless. She donates money to charity, especially Sufi dargahs, and carries on a genteel diplomacy with minor rajas who come to her with grievances and gifts,” writes Ira Mukhoty in her book.

Spending her last years in the pursuit of her artistic and humanitarian passions, Jahanara passed away in 1681 at the age of 67 but not before she etched her mark in the annals of history in a manner that would have made her father proud.

She commissioned several architectural spectacles, mosques, inns and public gardens across the Mughal empire.

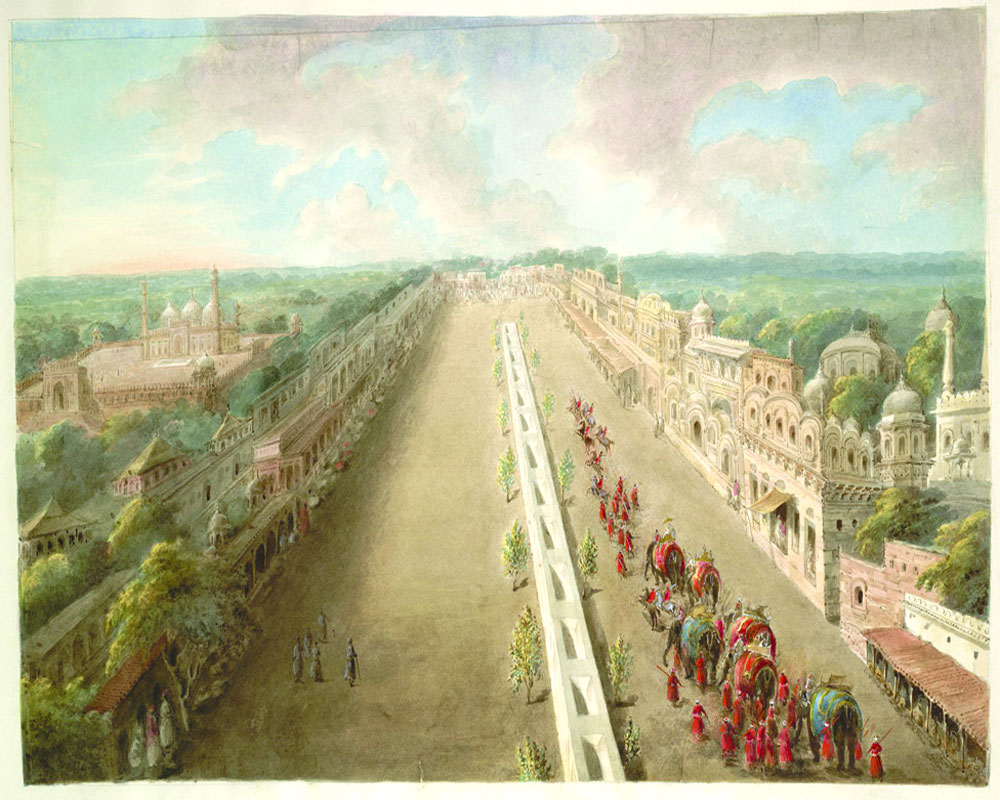

But she is best remembered as the architect of Old Delhi’s legendary bazaar, Chandni Chowk—which translates to ‘Moonlit Intersection’.

In his book Shahjahanabad : The Soverign City in Mughal India , Stephen Blake writes,

“The chowk was an octagon with sides of one hundred yards and a large pool in its center. To the north, Jahanara built a caravansarai (roadside inn) and a garden and, to the south, a bath. On certain nights, the moonlight reflected pale and silvery from the central pool and gave to the area the name Chandni Chawk (Silver or Moonlight Square). This name slowly displaced all others until the entire bazaar, from the Lahori Gate to the Fatehpuri Masjid, became known as Chandni Chawk.”

Today, many of Chandni Chowk’s ancient buildings have been torn down, as its lanes brim with new shops and colliding crowds. And yet, somehow it manages to invoke the spirit with which Jahanara lived—the same spirit that helped her survive and thrive amidst betrayals and tragedies.

Interestingly, Jahanara’s resting place in the Nizamuddin Dargah is of her own choosing, just like her character.

Unlike the giant mausoleums built for her parents, she rests in a simple marble tomb open to the sky, inscribed with her own couplet in Persian:

Baghair subza na poshad kase mazar mara, (Let no one cover my grave except with green grass,)

Ki qabr posh ghariban hamin gayah bas-ast. (For this very grass suffices as a tomb cover for the poor.

Perhaps it is poetic justice that green vines grow on the grave of this extraordinary princess of India.

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

source: http://www.thebetterindia.com / The Better India / Home> History> Women / by Sanchari Pal / May 24th, 2019