NEW DELHI :

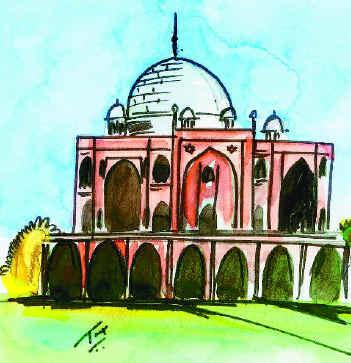

While Mughal rulers like Babar and Bahadur Shah Zafar have been buried on foreign soil, quite a few members of their clan rest at Humayun’s Tomb

Where do most Mughal kings, princes, and princesses sleep in Delhi? The answer lies in the vaults of Humayun’s Tomb, built with much devotion, by the emperor’s first wife, Haji Begum. Among those buried here are Hamida Bano Begum, the mother of Akbar; Dara Shikoh, Shah Jahan’s heir apparent; Aurangzeb’s once beloved son, Azam Shah; the dandy Jahandar Shah, and his slayer Farrukhsiyar; Ahmed Shah and Alamgir-II.

There are many more, of lesser note, some without inscriptions, gathered within the folds of the mausoleum of their ancestor Humayun. It’s a strange feeling of beds spread out on a summer night with the kind emperor sleeping in glory among many of those who waded to the throne through the blood of their relatives. The last rites of murdered princes were generally adhered to and they were laid to rest in the family graveyard. But there were exceptions like Dara Shikoh, who was denied the ritual funeral bath by his austere brother Aurangzeb.

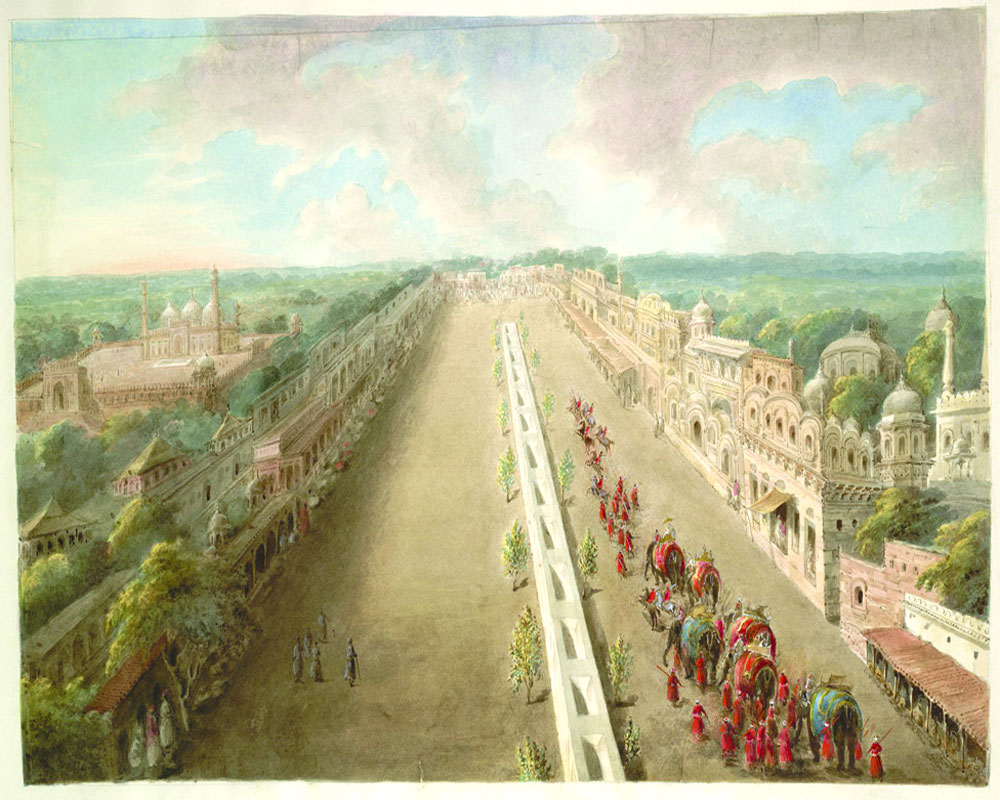

In Mehrauli, the precincts of the shrine of Hazrat Qutubuddin Bakhtiar Kaki also form the burial ground of many Mughal and other princes. In Agra, Akbar’s tomb at Sikandra is the repository of the remains of a host of princes and princesses. In Calcutta, several descendants of Wajid Ali Shah, the last King of Oudh, lie buried, and in Rangoon, the family of Bahadur Shah Zafar has found a burial place denied to it in the land of its birth.

Babar’s tomb should have been the last resting place of all those descendants whose graves are found in Humayun’s mausoleum. But Babar chose to be buried in Kabul which ceased to be a part of the Mughal empire by the time most of his successors died.

Isn’t it an irony of fate that the first and last emperors could not be buried in India? While Babar loved Kabul, Bahadur Shah Zafar had no choice as the British wanted to stamp out his very memory by burying him in a nondescript grave in Rangoon, which was rediscovered by chance and formed the rallying point for Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s INA during World War-II.

Bahadur Shah Zafar died on 7 November, 1862 and was hastily buried by lantern light, with the British officer deputed to escort him from India and look after his stay in Rangoon, supervising the funeral. Zinat Mahal and the other ladies of the harem who had accompanied the king did not attend the last rites, but his young son, Jawan Bakht was present. No tombstone was erected to perpetuate the memory of the star-crossed monarch, but fate willed it otherwise and Bahadur Shah Zafar seems to have had the last laugh as his name and fame survive despite his oppressors’ ill-intentions.

The king’s mazar (shrine) has now become a place of pilgrimage in Myanmar, where the last emperor is worshipped as a Pir. While on the walls are inscribed some of his heart-rending ghazals, like the one bemoaning the misfortune of his not having found even two yards of land in his country of birth “Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar dafan ke liye / Do gaz zamin bhi na mili ku-e-yaar mein”. But he has acquired enough space in the hearts of his compatriots alright.

Babar’s mausoleum is a modest one, which lay neglected for many years. But it is heartening to note that lately it has been renovated, having somehow escaped destruction during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and then the turmoil of the Taliban period. Though demands have been made for bringing back Zafar’s remains to India, nobody has raised their voice for Babar’s reburial, not entirely because of the first Mughal emperor’s dying wish.

So Humayun’s Tomb remains the funeral parlour of the family of Babar. You go from vault to vault and nothing but inscribed stones confront you on which are enshrined a cloak-and-dagger mystery. Death, gruesome death, generally at the hands of an assassin hired by the next of kin, the ambitious prince determined to seize the throne.

Many were done to death by their brothers, uncles, nephews or treacherous wazirs. Some died of poison, administered through a favourite, but faithless, courtesan; others strangled in their sleep, yet others hacked with swords or stabbed through the heart or back. Children weren’t spared. You gaze at these tombstones with awe and pity. How many innocent lives destroyed for the sake of ambition! There is the silence of death all around, with the Grim Reaper gloating over his sickle of time with which he has laid low both those with name and those without fame. Only Clio, the muse of history, understands the secrets of these vaults and it is she who weeps in them through her tresses: Put on your shoes and tip-toe away.

The writer is a veteran chronicler of Delhi

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture> Down Memory Lane / by R.V. Smith / July 23rd, 2019