Chennai, TAMIL NADU :

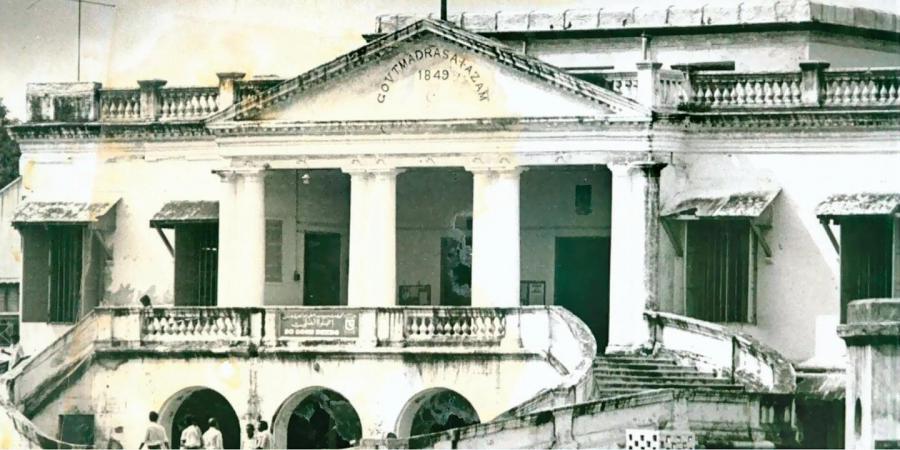

Behind the crumbling facade of the Government Madrasa-e-Azam Higher Secondary School, there is a rich history of academics, and tales of friendship.

The majestic doublewinding staircases that lead to the splendid balcony and upper deck; the steps to the headmaster’s office on the first floor and the huge plaque outside the room, with the history of the structure chiselled on it; the jamun trees in the backyard and the numerous other trees dotting the campus, under which I spent several afternoons — I have fond memories of my school.

Looking at the grandeur of the structure and the greenery, I often used to ponder ‘The seeds for these trees were planted over a century ago…’ It used to feel surreal, it still does. But unfortunately, these very trees are taking over the structure now,” says Sharfu Khan, an alumnus of the Government Madrasa-e-Azam Higher Secondary School, who was also the SSLC topper of the institution in 1992.

The 200-odd-year-old magnificent campus — with a Madras terrace, tiled verandahs, and semicircular arches — spread over 15 acres in the heart of Chennai, used to have over 4,000 students on its rolls. But today, barely 200 schoolboys study at the campus, which was initially owned by Colah Singanna Chetty, a dubash. Since 1816, the building has been acquired by many prominent individuals including Edward Samuel Moorat, an Armenian millionaire; Ghulam Ghouse Khan, the last of the titular Nawabs, after whose death in 1855, the property was passed on to Azim Un Nissa Begum, the nikah wife of the Nawab. According to historian Sriram V, the property, though owned by her, was rented by the principal wife of the Nawab, Khair Un Nissa and became the social epicentre of the Muslim aristocracy in Madras.

“This was where luminaries such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, founder of the Aligarh Muslim University, and His Exalted Highness Mir Mahbub Ali Khan Bahadur, the Nizam of Hyderabad, stayed when they visited Madras,” he writes, in When Mercy Seasons Justice, a book on jurist Habibullah Badsha, a prominent alumnus of the school. Today, the historic estate, with corporate offices, heritage buildings like the Taj Connemara and Spencer Plaza, and the buzzing traffic necklacing its perimeter, bears a deserted look, is crumbling under the thick foliage and yet, is resiliently waiting to be restored to its former glory. “Our school used to be the exam centre for schools in and around Triplicane and Mount Road.

Several hockey and sports tournaments used to take place here. It’s been over two decades since I graduated from there, but the memories are still fresh. I very recently became acquainted with an old friend, a batchmate from the Madrasa and we are hoping to pay a visit to the school or at least what’s left of it once the COVID-19 situation eases,” shares Sharfu.

A modern transformation

When the British took control of all the properties of the Nawab, Edward Balfour, an agent of the East India Company in the court of the Nawab of Carnatic, persuaded the Nawab to transform the family’s Madrasa into a modern school. He suggested it could be called the Madrasa-e-Azam, after his father Nawab Azam Jah, who had first favoured a proposal by Balfour. “As early as 1846, the first proposal was sent to the government regarding the starting of a school for the orphaned children of Carnatic territories. The proposal materialised, and the school was soon started.

At that time, there were only three teachers,” says Ashmitha Athreya of Madras Inherited, about the institution, which until 1849 was functioning at Chepauk, before moving to its current premises. Historians Kombai Anwar and Venkatesh Ramakrishnan, while sharing glimpses of the structure’s early glory, also note that much before Muslim institutions in north India took up modern education, this school introduced the study of English, Tamil and Telugu besides Arabic, Persian and Urdu. Abdul Jabbar Suhail, son of Habibullah Badsha recalling the anecdotes shared by his father about his days at the Madrasa, tells us that his father “had an enriching experience at the school.

My father studied at the Madrasa-e-Azam during the 1940s, at the time of World War II. For someone who until then had studied in an Anglo-Indian establishment, the change was stark. But, on the persuasion of his maternal grandfather, he enrolled at the Madrasa. Despite there being issues like inadequate staff members, I remember my father telling me that he had a good time there.

He did very well in school. And as far as sports was concerned, the school was a powerhouse and produced stalwarts including Muneer Sait, Abdul Jabbar, Badiuddin and Mohamed Ghouse. Muneer even went on to represent India in the Olympics in hockey. Father was in touch with most of his friends from school till his final days…he loved the place,” he shares.

Mohammud Karim, Zeeshan Bismil, Basha Shareef and several other alumni, who are now spread across the globe, tell CE that they miss the campus for all that it has given them. “A common thread of sadness has now tied us together. After the 1970s, I never visited the school. I didn’t know of its condition. Recently, I came across a few pictures and I was crushed to look at its current plight. I hope the government takes steps to preserve the building,” shares 67-year-old Karim, who currently lives in the US.

An appeal

In 2017, if the government had had its way, the collapsing building, would have perhaps hosted grand weddings at its age-old premises instead of conducting classes. But thanks to the voice of the city’s heritage enthusiasts and alumni, a division bench of the Madras High Court announced that the building shall not be demolished until further orders. But with growing apathy and neglect, its future remains uncertain. In an appeal to the government, Prince of Arcot, Nawab Mohammed Abdul Ali tells CE, “The Madrasa- e-Azam was founded by my ancestors for the primary purpose of providing education to children from Muslim communities and other minority communities.

After it was handed over to the British, from being an exclusive Urdu medium school, it also included English in its curriculum. Over the decades, the quality of education and the standard has been very minimal. Several parts of the structure have collapsed and as a result, the student strength has also alarmingly dwindled. As the Prince of Arcot, the direct descendent of the founders of the Madrasa, I appeal to the government to hand over the management and administration to us.

I do not ask for the ownership but only the administration wherein, under the Prince of Arcot endowments, we can take care of the structure, and provide quality education. We will not only keep the legacy of our ancestors alive but will also be enabling the conservation of the original vision and mission of the Madrasa — to provide education,” he says.

SLICE OF HISTORY

- Balfour, the government agent at Chepauk, and Garstin, his predecessor, framed the rules for the administration of the school. With the establishment of the school, the Nawab also had in mind a secular education that would help the Muslims to secure employment in government service.

- The main aim of establishing the school was that it would be a means of encouragement to the students to educate themselves and be fully qualified and competent for getting their livelihood by being employed in public offices, after obtaining certificates of proficiency at a final public exam.

- The Diwan Khana of Firuz Hussain Khan Bahadur, principal-agent of the Begum Khair Un Nissa, became the residence of the school principal.

- A mosque was built on the campus in 1909. In the same compound, the Government Mohammedan College was set up in 1919.

Source: Madras Inherited and ‘When Mercy Seasons Justice’

source: http://www.newindianexpress.com / The New Indian Express / Home> Cities> Chennai / by Roshne Balasubramanian / Express News Service / August 05th, 2020