Hyderabad, TELANGANA :

On the Idara archives’ efforts to preserve Deccan literary, artistic, and historical cultures..

Between the din of the city, two Hyderabadi historians exchange WhatsApp messages:

“Where are you?”

“I’m at Idara. Something is always going on here.”

“Oh, I wish I was there with you! What is happening over there, right now?”

“Four-hundred- and- fifty-year-old Golkonda fort era tope arrived. Some men just carried it in.”

“Tope as in arms and ammunition, or something else?”

“Yes, the old armaments. The Qiledars’ descendants didn’t want to keep them in their house anymore, so they are giving them to Rafi Sahb,”

“Oh wow. Amazing. How is Rafi Sahb?”

“He’s good. He’s happy to be interviewed. He’s asking about you. When will you be coming back here.”

“I’ll be there later this week. I really wish we could do something for Idara.”

“Maybe we can start with writing an article about this place?”

***

Whose knowledge? Which archives?

Barely visible from across the new Errum Manzil metro and crushed between rows of commercial buildings, lies an abandoned citadel of knowledge: Idara-e Adabiyat-e-Urdu.

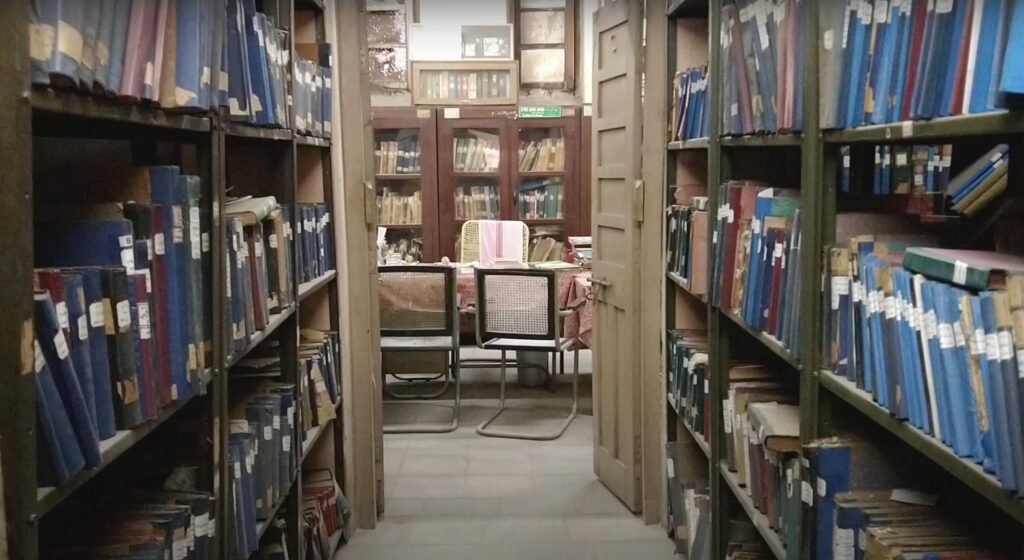

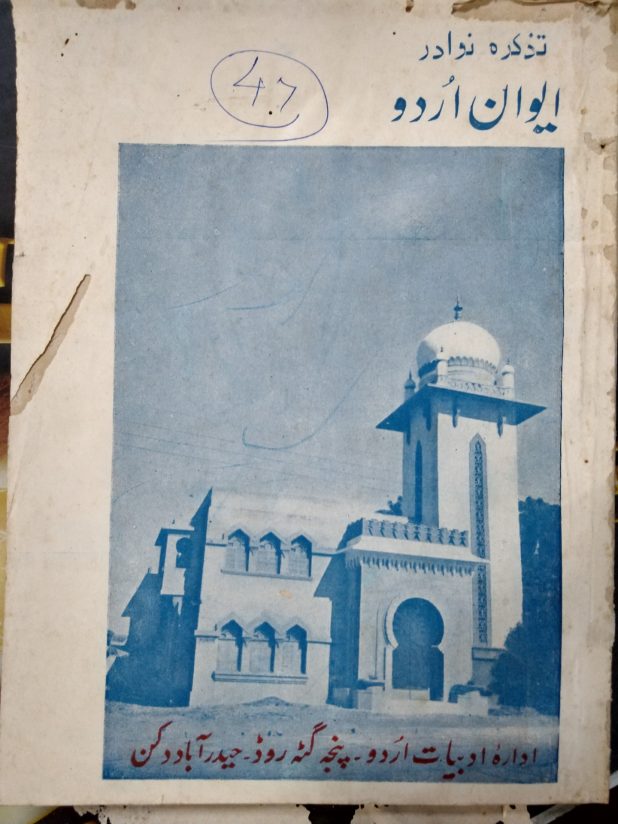

Once a core institution of the city for scholarship of the Deccan, this vast library and its museum, Aiwan-e Urdu – like much of Hyderabad’s heritage – exists in a state of disrepair. It is one of Hyderabad’s fast disappearing independent archival institutions connected to a time before – as ruins beneath the consumerist ravages of the new city. And yet, as we step inside, walk up the stairs to the library in its tower, rummage through dusty catalogues and forlorn books – it feels as though we have entered a magical portal into another world.

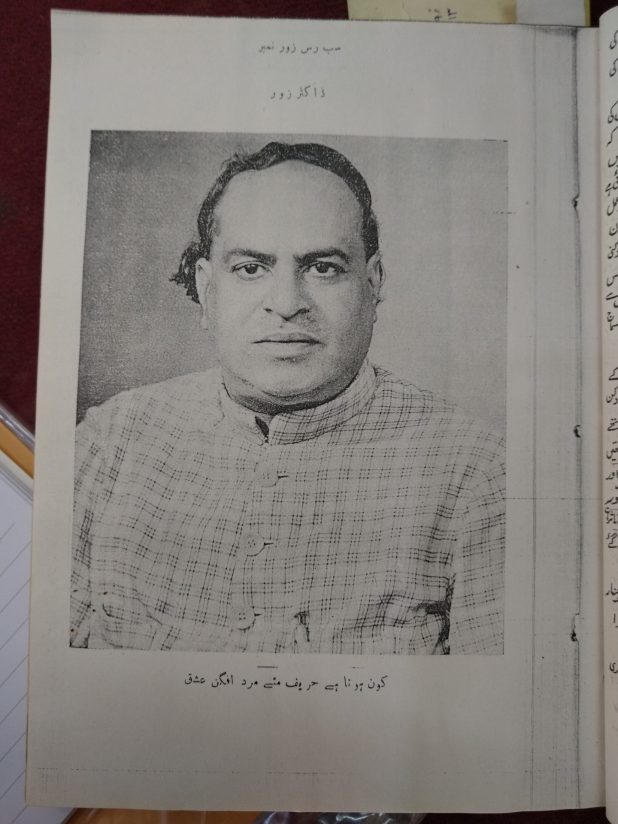

Established in 1931 by Syed Mohiuddin Qadri Zore (1905-1962), the most prolific scholar of the Deccan, and built upon lands donated by his wife, the illustrious poetess Tahniyatun-Nissa begum, the Idara houses a vast archival collection. That the library and museum continue to exist at all is due almost entirely to their 73-year-old son, Rafiuddin Qadri, who has devoted himself to managing this house of knowledge. Containing over fifty-thousand books and printed materials, including manuscripts and paintings and artefacts, the purpose of the Idara was to preserve the art, history, and multilingual Deccan literary cultures in Urdu Dakkhani, Persian, and Arabic.

Video: Click on the Link below:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/19DesGVa2OsTgA5Ck5IxF3zlAzgYZZ6a3/view

At a cursory glance, the closed doors of the book shelves seem dense and inaccessible. But if one is willing to subject themself to the rigours of an erstwhile knowledge production circuit and has the patience to listen to its many stories rendered in multiple languages and idioms, these doors open up fascinating worlds.

Here, beneath dusty glass encasements, is an original eighteenth-century painting of warrior queen Chand Bibi of the Deccan, and a book about Deccan Radio. The museum is typically kept locked and desperately needs restoration. A dusty lithograph of sixteenth-century Qutb Shahi tughra emerges in fragile condition, alongside an original photograph of Kishen Pershad, an erstwhile prime minister of Hyderabad State under the Asaf Jah Nizams. The museum contains rare royal firmans, inscriptions, maps and genealogical trees, arms and weapons, coins, old garments and cloaks that are not available anywhere else.

Behind this seemingly random collection from the past is the erudite vision of Zore, who was not only a scholar himself but also carefully curated and fostered the production of knowledge.

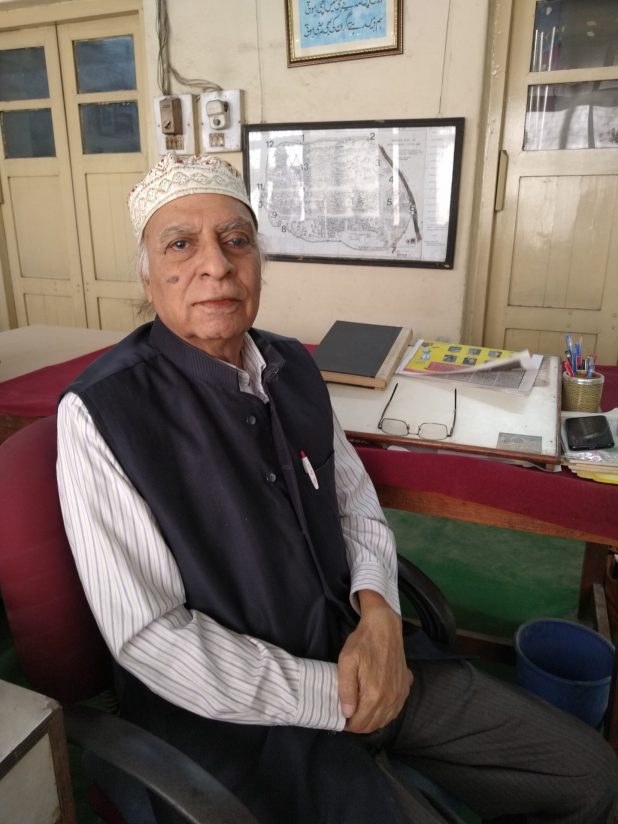

Zore’s son Rafiuddin Qadri sits at a desk in the main hall, surrounded by construction workers, painters, and piles of decaying books and magazines. The sound of traffic on the main road tends to drown out his voice. He is the last of a generation to remember why institutions such as the Idara emerged in Hyderabad during the early to mid-twentieth century. He is soft-spoken, donning his characteristic vest and topi. He carries a dignified scholarly attitude resonant with an earlier time. Exceedingly generous and patient, Qadri carries on a legacy that no longer is valued by the current trends of historical knowledge production in India.

Archives and libraries everywhere in India are under threat of some kind, as history literally rots away . Hence, when serious historians come across independent archival institutions and archivists devoted to the preservation of historical knowledge – like Rafiuddin Qadri – it is worth telling their story.

Once a core institution of the city for scholarship of the Deccan, this vast library and its museum, Aiwan-e Urdu – like much of Hyderabad’s heritage – exists in a state of disrepair.

Descended from a Sufi family of Qandhar and North Deccan, Rafiuddin Qadri’s ancestors came to Hyderabad in the late nineteenth century. His father, Syed Mohiuddin Qadri Zore maintained close ties and commitments to Sufism, both in institutional ways regarding his familial lineage and his philosophical approaches in terms of the spiritual values attributed to seeking out knowledge. Sufi dargahs have traditionally been not only spiritual centres but also major arenas of producing knowledge. At the same time, Zore was a modern visionary, establishing a major institution of learning in Hyderabad, in keeping with the time. “The dawn of the twentieth century was an era of renaissance in the Deccan,” and “a number of institutions such as Asafia Library, Osmania University, Dairatul Maarif, Dar-ul-Tarjuma, Salar Jung Museum, were established which contributed immensely to the production of knowledge about the history and culture of Hyderabad.” Zore was not only a major scholar-administrator – publishing hundreds of books and editing the magazine Sab Ras – he was a key figure who brought together intellectuals while establishing and overseeing the Idara, with the help of his friends, ranging from scholars to local politicians and administrators. This spirit lives on in Rafiuddin Qadri.

Schooled as we have been in the contemporary formalities of accessing archives, when we asked if there was a fee we ought to pay to access the library, Rafiuddin Qadri said, “No, not at all,” and then explained his father’s legacy. “Knowledge should be free”, is the principal hallmark of the Idara. “It is completely against my father’s ethics that one should charge money to scholars as this is a place for them to study and learn freely.” This ethics of scholarship and the writing of history is lost as a result of the commercialisation of intellectual production as well as the privatisation of education in India. “It was meant for the youth of Hyderabad,” says Rafiuddin Qadri, about one of the main purposes of establishing the Idara. “The youth were involved in the world of politics constantly, at a very turbulent time,” referring to the anti-colonial nationalist movements of the 1930s and 1940s. “A quiet space of inquiry was needed where they could go to do intellectual work and to study.” The Idara, then, is a physical space and has served as a much-needed refuge from the noise of the world’s polemics, to think, ponder, reflect, and read, without the constant interruptions of the fast-paced intensity of daily urban life in India, and its demands.

‘Scholars come from all over the world. They say, how did Zore know I would need this document so many years later! He had preserved it!’

The extraction of knowledge out of India and into the corridors of more powerful contexts of intellectual knowledge production – such as academia in the West – has contributed to diminishing the role of those who have cultivated the very libraries and institutions so central to academic research about India. It is often suggested that only British libraries and archives are worth perusing when it comes to various aspects of India’s past, given the colonial codification of Indian knowledge – brought there often by way of loot – were preserved there. Moreover, popular histories of the Deccan for a commercial market dominated by elites and their publishing houses tend to overlook vast swathes of historical knowledge produced in languages other than English, such as Urdu. Zore had been vital to Hyderabad in creating a space, a physical place, a free and open library – of which there are few and far between today. The very idea of a library – one of the few spaces which anyone can visit without having to spend money – is itself a revolutionary idea in contexts such as India. The institution Zore created is today preserved by Rafiuddin Qadri, who belongs to the last generation of living reposit.

Rafiuddin devotedly handles the materials, and carefully walks the corridors he has seen during the many seasons of his life. His eyes light up when he narrates the stories of researchers: “Scholars come from all over the world. They say, ‘how did Zore know I would need this document so many years later! He had preserved it!’”, he muses.

Deccan: A region that resists categorisation

“Even though local Indian historians may know more about the Deccan, they won’t get published as easily as outsiders in the top international presses.”

“This is true. But I feel like we do the same thing unfortunately. Produce knowledge for the West.”

“History as a profession in India seems so dead. The assault is coming from all sides. The propagandistic writing to fit the current ruling ideology, the evisceration of educational spaces, the lack of care, no thought.”

“It’s so depressing.”

“So, how do we talk about the Deccan amidst all this? No one seems to care.”

“Just keep going to the archives and keep writing.”

“Yes, Rafi Sahb is waiting.”

“Is he there now?”

“Yes, he is.”

Rafiuddin Qadri points to the calligraphic poetry of Dakkhani Urdu gracing the high arches of the main hall of the Idara, with its main chandelier, overlooking what once was a clean and orderly library. “This place is not what it once was, there are very few people who are interested in doing serious work like this in Hyderabad,” he says. It is true. The archivists and knowledge-keepers of these earlier institutions are passing away while their knowledge is not being passed down. As we ask Qadri questions about our respective research projects, he says, “Did you ever meet Zia Shakeb?” We shake our heads. Qadri puts his hands to his head. “Oh, that is too bad. He knew so much. And now he is gone. So much is gone and lost.” In describing the history of the Idara-e-Urdu-e Adabiyat, Qadri also shares with us some old photographs detailing the networks of people instrumental to this library.

Zore imagined Idara, with a differently rooted aesthetic, as a space for people from different languages of the Deccan to work together, to have intellectual camaraderie without being subjected to the pressures of capitalist cycles of publish or perish production.

Qadri shuffles slowly between different rooms of the Idara, all under some kind of construction. He seemingly is displaced not only by time, but also between the once vibrant rooms of his family’s library. Over cups of chai, as we discuss historical research, he advises us about specific catalogues and indexes as he repeatedly issues unheeded calls for the library staff to retrieve particular titles.

What happens once these archives, knowledge, and the custodians of stories about the past are lost? One easy answer is that the region takes on a new identity, more sectarian, more oppressive and discriminatory, built around invented histories that weaponise pasts as archives diminish. Perhaps, a more creative and bolder answer would be, that we increasingly become a society alienated from oneself, lost and rootless – our understanding of history diminished by corporate and profit-making knowledge enclaves such as within the dystopia of a hi-tech city and financial district, Hyderabad’s rapidly developing new urban core. It is the responsibility of professional historians to keep stories of the past in circulation, in the hope that they might make us more empathetic, caring and humane.

Although Qadri claims his memory is fading and not what it once was, we marvel at his ability to recall catalogues, titles, essays, authors, scholars, poets, and multiple editions of books and magazines, produced about the Deccan between the 1930s and 1960s. This earlier period of scholarship about Dakhaniyat is largely ignored, as knowledge produced in the languages of this region, such as Urdu, is not considered as worthy as compared to knowledge produced in English.

The Deccan has long been configured as a region of hope in history, offering alternative ways of belonging, those that do not fit within the nationalist frames of India and Southasia overall.

It is in response to European dominance over the circuits of knowledge about India, that Zore imagined Idara, with a differently rooted aesthetic, as a space for people from different languages of the Deccan to work together, to have intellectual camaraderie without being subjected to the pressures of capitalist cycles of publish or perish production. Accessing the Idara today is not just about mechanically sifting through catalogues until you find what you need, and extracting it – but more about setting the pressures of clock-time aside and the arrogance of earned professional degrees aside, to learn from a life-long archivist. It means opening one’s self up to the humbling, slow and feeble processes of identifying voices in history, which are increasingly lost in the maddening clamour of the market and the deafening contours of nationalist totalitarianisms and fascisms of today.

Interest about the Deccan is growing in India, and new works of popular history have emerged in recent years. There has been some recent acknowledgement that the history of the Deccan has been marginalised, and as one headline pronounced, “Indian history without the Deccan is like European history minus France” for it seems that comparisons to Europe must be made, if Southasian regions are to exist at all within the historical imagination or reading public. Overall, it is the north-centric perspective of India’s historical narratives that continue to dominate Southasia’s study of the past. This is a perspective that largely ignores the Deccan region – today, home to the four linguistically organised states of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. Southasian historians continue to favour and focus upon Punjab, Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh. Meanwhile, it is the Mughal era that dominates scholarship on Southasian Islam when turning to India’s medieval and early modern past. Turning to the Deccan region thus challenges the north-centric perspective of Mughal imperial development that dominates histories of India’s Persianate past.

And yet, it is impossible for any serious scholar or historian undertaking research about Deccan or about Hyderabad – once India’s largest and wealthiest princely state – without coming across the legacy of Syed Mohiuddin Qadri Zore.

Rafiuddin Qadri points out a special issue in Sab Ras about his father in which the author points out that, “Dr. Zore gave voice to the Deccan,” during a period of time in India’s history when communal tensions were on the rise. His was a utopian project of “knowledge for the people,” about a region of Southasia with its own distinct role and shared pasts that cut across religious, linguistic, and communitarian identities. It is to Zore’s credit that the Deccan was situated at all in the historiography of the subcontinent, being one the first scholars to research and write seriously about this region. Zore’s legacy is astounding, and he is, in fact, a key figure in India’s intellectual history. Yet, he has been ignored by historians of India. To write about him means having to situate oneself between the missing pages of Southasian historiography and history, between emphasising the importance of ethical citational practices amidst fast disappearing archives.

The Deccan has long been configured as a region of hope in history, offering alternative ways of belonging, those that do not fit within the nationalist frames of India and Southasia overall. Nawab Ali Yavar Jung, the Vice-Chancellor of Osmania University in the first session of the Deccan History Conference held in April 1945, which was sponsored by Zore said “…the history of the Deccan is, in miniature, the history of India. It mirrors all the great reflexes of Indian History and throws its own reflection back on that larger screen…. Separateness in the midst of geographical unity, isolation in the midst of invasion, such have been its characteristics. The resistance of the south to northern pressure provides an instance of the centrifugal forces which baffled successive efforts to establish one and the same rule over the length and breadth of India…” The region carries the spirit of sovereignty and diversity and this was championed by Idara and Zore. Though not like what it once was, in Hyderabad Deccan there still continues the intermingling of the languages of Telugu, Urdu, and English, with a sprinkling of Marathi, Kannada and Tamil.

The pluralism and cosmopolitanism of the Deccan is reflected in the physical building of the Idara itself, whose construction occurred in 1955, with the patronage of the Government of India, the Nizam Trust, and several other entities in and outside of Hyderabad, from the state of Andhra Pradesh to Kashmir – where Zore was eventually laid to rest. The Indo-Islamic architecture and designs are inspired by Qutb Shahi domes, Indic lotuses of Hindu mythology, Bahmani latticework, flowering buds of the Egyptian Nile, and Spanish minarets and arches, with a main front door meant to represent the gates and doorways of so many forts of India.

Not only was Zore among the chief intellectual architects of Dakhaniyat, he was responsible for building several educational institutions and was at the helm of vast intellectual production. His entire education through his Masters degree was completed in Hyderabad. Born in 1905, Zore was educated in a primary school in a Kayasth Pathshala, where he learned English, and where his fondness grew for poetry, public speaking and debate. By high school he had not only already established a debate society but also a small library. He later joined Darul Uloom and City College and ultimately the College of Arts and Social Sciences at Osmania University.

Descended from a Sufi family of Qandhar and North Deccan, Rafiuddin Qadri’s ancestors came to Hyderabad in the late nineteenth century.

Osmania University is the first university in India to introduce a vernacular language (Urdu) as the medium of instruction. It aimed, among other things, to translate knowledge, including science textbooks into Urdu, which was a remarkable project, and contributed to a cosmopolitan ‘worlding of the Deccan.’ There, Zore eventually became Head of the Department of Urdu, where he was a founding member of ‘Mujalla-e Osmania’, the first Bilingual English-Urdu magazine at Osmania University. He was the first to work seriously on Urdu-Hindi linguistics and phonetics, and later published a book called Ruh-e-Tanqid, which was one of the earliest works of Urdu literary criticism. Widely travelled, journeying to London, Paris, as well as to Germany – where he learned French and German and translated Dakkhani Urdu poetry into European languages – Zore also travelled extensively within India, and to Kashmir and wrote the first book about Dakhaniyat. A polyglot, linguist, and philologist par excellence, Zore had studied Sanskrit and Gujarati as well.

During the mid-1930s, he embarked upon a project to prepare an encyclopedia in Urdu, inviting Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Sarojini Naidu, and Jawaharlal Nehru to write for it – many of whom had met with Zore. Though the encyclopedia project itself was not realised, the attempt signalled the yearning to produce knowledge about the world for citizens of Hyderabad, to bring in a perspective from the Deccan and its relationship to the wider world. And yet, his legacy is in danger of being forgotten, as Zore’s understanding of the Deccan has never been included in the story of India. The Idara-e-Urdu-e Adabiyat and the Aiwan-e Urdu are institutions that themselves could form the subject of an entire PhD dissertation as well as serious scholarship about Hyderabad’s institutions.

Erasures: The city and the politics of historical memory

Hyderabad’s past is rendered almost invisible: over the past 75 years, there has been tremendous upheaval: from a former Muslim princely kingdom – capital of the Asaf Jahi dynasty – to its violent annexation by the Indian state and army in 1948; and then its incorporation into the state of Andhra Pradesh in 1956; its land reallocations by the linguistic state in the 1970s and 1980s; the neoliberal economic reforms of the 1990s; and then being cast as the capital of the new Telangana state in 2014, the same year India was met with the political triumph of Hindu nationalism. And, it is not only upheavals.

Hyderabad’s history is also marginalised by most historians of India, who have simply not paid close enough attention to this city and its past. Then, there is the fact that popular historians write of Hyderabad’s history in romanticised ways, subjecting its past to their own perspectives, whether nationalist or colonialist, while Hyderabad’s elites produce accounts imbued with relentless nostalgia. Since 1948, there has been a steady demolition of Hyderabad’s historical pasts, inaugurated by the Indian state as well as by a combination of other factors – including the increasing out-migration of the city’s elites who were once patrons of major institutions. They have been replaced by a new elite who care more for malls, sports cars, and bars – and see no value in patronage or cultivation of the arts, cultural activities, or historical knowledge.

Today, the erasure of Hyderabad’s pluralist past is occurring at a resounding pace. The assault upon this city’s history and the shared heritages of its people is tremendous. Buildings torn down, monuments subject to land-grabs by the state or by private entities, and the city’s heritage continues to be destroyed by new capitalist ventures, as the old sixteenth century urban core and the modernising reforms of the Nizams in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, is decimated by hyper-development, political expediency, and the corrupt scions of progress.

Yet, at the same time, there do exist responses to these assaults by Hyderabad’s numerous heritage activist groups and citizen historians, who daily record, bear witness to, and struggle against the demolition of monuments. While they are few and far between, they frequently lack political backing. There are organisations and individuals on the ground in Hyderabad who are constantly challenging the assaults on Hyderabad’s heritage. Local heritage activists and citizen historians, to several social media groups which have cropped up in recent years, are imbued with a very strong historical consciousness – doing everything from pleading with authorities to preserve heritage, leading heritage walks, to writing extensively about it in newspapers, such as The Siasat Daily – which regularly contains articles about Hyderabad’s heritage. One has only to bend one’s ear and take the time to listen.

Existing alongside these erasures of Hyderabad, is the continued persistence of historical memory among the people of the region. They consistently recall the shared past of the city across different communities and frequently invoke history. Even such mundane activities as providing directions in Hyderabad, constitutes broken maps of history. Directions include not only present landmarks, but also the names of people, properties, and heritages that existed in those same places of an earlier time, for Hyderabad once had the characteristics more akin to small town life – rather than the megapolis it is today. The lanes of Hyderabad are full of oracles who narrate the past. One octogenarian asks, “in the Nizam’s rule, Hindus worked as prime ministers, can Muslims now even be peons of government offices?” voicing some facets of changes the city and the nation have seen. Once the Muslim elites’ lands were confiscated and thoroughly eviscerated by the state, through their displacement as well as their own migrations to the Global North, the past few decades have witnessed the arrival of a set of new elites to the city. They are all too happy to culturally appropriate the memory of the Nizam, while at the same time encroaching on lands in celebration of an “India Shining” with its new temples rooted in the free-market economy – just one endless shopping centre–part of a larger drive that is flattening and homogenising India.

Meanwhile, the politics of the memory of Hyderabad are complicated and are constantly reframed, sometimes they take the shape of the claiming of a shared “Ganga Jamuni Tehzeeb” (Hindu-Muslim culture or harmony), at other times, equating the entire Nizam period with communal rule. What is lost here in the polemics is the complexity of the Deccan, and the region’s capacity to uphold diversity and resist totalitarianism. Qadri’s and Zore’s Idara, and vanishing documents enable us to tell these stories of defiance in the face of erasure.

Women in history, women doing history

The role that women have played in the production of historical knowledge tends to be cast aside in the writing of institutional histories of India – where they are frequently rendered into a separate category of appraisal. In the anthology of poetry produced by Tahniyatun-Nissa begum (1911-1994), who donated her lands so that the Idara could be established, the poetess writes, “bahut baatein hain yun tou tahniyat dunya mein karne ki / hum apne shauq ki apni lagan kii baat karte hain,” “There are many things celebrated for discussion in this world/I follow my own desires, and speak of things which are close to me.” The couplet is an apt reminder of following one’s own individual path amidst that world’s demands for conformity. A devout woman, who was linked on her maternal side to the respected ‘ulema [religious scholars] of Firangi Mahal in Lucknow, Tahniyatun-Nissa begum was educated at Mahboobia Girls High School and went on to pass Senior Cambridge exams in the late 1920s. At the time, for Muslim women to be formally educated at this level, was itself a significant achievement.

Tahniyatun-Nissa begum wrote a great deal of poetry, her specialisation was in ‘Naat’, a genre of Urdu poetry in praise of the Prophet Muhammad. She is reputed to be among the first female poets to have a collection of published works in the Naat genre. There are at least three collections of her poetry, including Zikr-o-Fikr (1955), Sabr-o Shukr (1956), and Tasleem-o Raza (1959). Aside from her poetry, Tahniyatun-Nissa begum was devoted to sustaining the inner everyday workings of the library and museum. Qadri speaks of his mother fondly, recalling how the Idara was managed not by Zore alone, but with the magnanimity of Tahniyatun-Nissa begum. Her existence graces these halls, as he points to where she would organise gatherings for women who were scholars and writers in their own right, and even acknowledging the steps from which she once had a fall.

The Idara initially was a male space, but it was not long before the library began to open its doors to women. Qadri discusses how it was important to his parents that a place and space be made for women scholars. “Today, it seems that it is mainly women scholars who come to seek knowledge here,” he says, reflecting on the irony.

Hyderabad’s history is also marginalised by most historians of India, who have simply not paid close enough attention to this city and its past.

As Qadri unlocks the museum, hidden at the top of the tower of the Idara, it is the portraits of women that are most immediately noticeable, gracing the walls above the filigreed and cobweb-covered windows. They include notable women of Hyderabad State, such as Mah Laqa Bai Chanda, the 18th-century poetess of Urdu, and frequently known as the earliest major female poet of Urdu – though there were others before her. There are at least two portraits of her on the walls – she was a high-ranking court noble of the Asaf Jah state, talented in music, the arts, dance, as well as poetry and hunting. Her devotion to Maula Ali is evident by her mausoleum near the Maula Ali Dargah in the city.

There are paintings and sketches of Premamathi and Taramati – a kuchipudi dancer and the courtesans of the Quli Qutb Shah dynasty from the sixteenth century.

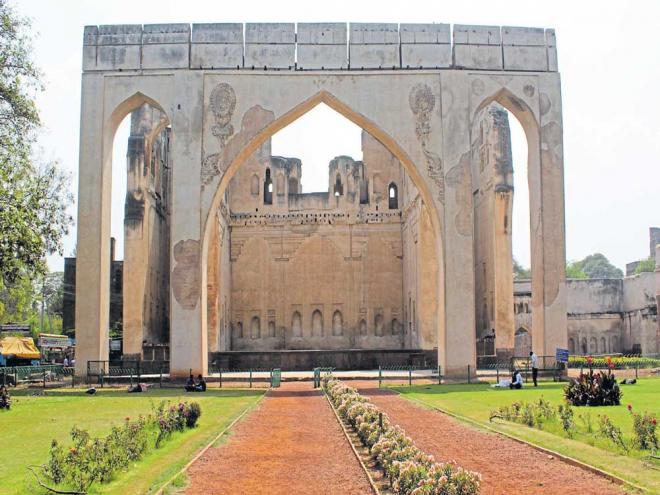

There exists today a serai (caravan station), named after one of them, the Taramati Baradari, built under the reign of Ibrahim Quli Qutub Shah. According to local legends, the sultan was awed by her voice when she sang for the weary travellers and the sounds of her song were carried by the breeze all the way to Golconda Fort.

At a short distance away, there is a mosque of Premamati – and both dancers are buried in the Qutb Shah mausoleum, north of the serai. There is also a portrait of Bhagmati, a legendary courtesan (and later queen of Muhammed Quli Qutb Shah, the founder of Hyderabad city in 1591). Bhagmati’s very existence, or lack thereof, is today the source of considerable controversy.

There is too, a rare portrait of the sixteenth-century warrior queen Chand Bibi, a regent of two Deccan Sultanates.

About Chand Bibi, Zore was critical of how she was dismissed by scholars of his time, writing in 1938 that the “king’s birth, pedigree and influence of Chand Sultana of Ahmadnagar who was his aunt should have been dealt with in a detailed manner…it was she who made him a man of letters, a broad-minded gentleman, generous king, and valiant warrior.” That there was an entire section dedicated to the women of the Deccan, during the early twentieth century – when there is yet to be any serious scholarly books today in English focused upon women and female power within the Deccan – itself indicates attempts for inclusivity within the imagination of the Idara.

Yet, beyond these more well-known names, the Idara itself opened its doors to female scholars and poets of the twentieth century. Qadri tells us the story of how women scholars were patronised by the Idara, and that the institution accommodated them as “gosha-purdah” women would come here to study and research. At the time, this was a novelty, signalling new forms of educational possibilities for women. Today, almost one hundred years later since the conception of the Idara, the historical profession in India continues to be dominated by men, who in turn, continue to produce visions of the past in which women do not exist, with the frequent claim that obtaining records of their existence is next to impossible. It is perhaps not a coincidence that today, we are two women inviting some reflection and further research about the Idara, with a reminder that the legacies and the lineages of the past continue into the present.

***

It is 8pm in the evening and we have finally found a quiet spot in the city. We have taken the steps up to Maula Ali pahaar, at the top of which is an old Shia shrine. We take our place upon an expansive rock formation, offering its vast open natural space to us, with some quiet space all around, and stare out to the city of lights below. As we dream and talk about the need to create and preserve spaces of plurality, free inquiry, openness, and camaraderie, the historical city of Hyderabad vanishes beneath us.

*** SARAH WAHEEN AND YAMINI KRISHNA

Sarah Waheed is Assistant Professor of History at University of South Carolina. She is the author of Hidden Histories of Pakistan: Censorship, Literature, and Secular Nationalism in Late Colonial India. She is a Fulbright Scholar writing her second book, about Chand Bibi and women of the Deccan: The Warrior Queen Who Died Thrice: Gender, Sovereignty and Islam in Premodern India. She can be reached at sarah.f.waheed@gmail.com.

C Yamini Krishna works on film history and urban history. Her work has been published in South Asia, Historical Journal of Film Radio Television, Widescreen, South Asian Popular Culture, The news minute, Caravan and Scroll. She currently teaches at FLAME University. She can be reached at yaminkrishn@gmail.com.

source: http://www.himalmag.com / Himal South Asian / Home>Commentary> Culture> India / by Sarah Waheed and Yamini Krishna / July 19th, 2022