Moradabad / Gond, UTTAR PRADESH:

Guru Dutt’s masterpiece ‘Pyaasa’ (1957), just before its soulful dirge on relationships, shows two poets reciting ‘shers’.

The elder one later also politely reprimands a guest for his snide remark at the “servant” (Dutt), who had begun humming “Jaane woh kaise log the..”, declaring: “Mian, shayri koi daulat-mando ke jagir thodi hai”. Though unnamed, his appearance, sher, and comment were enough to identify him.

Urdu Poetry and Social Reach

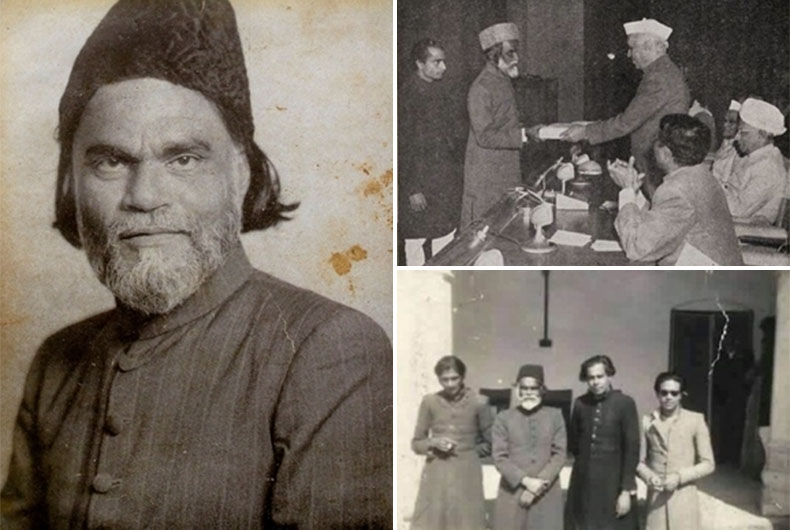

The unnamed actor was representing Ali Sikandar ‘Jigar Moradabadi’, who, in his heyday, was so known by his persona – an intense gaze but an air of absent-mindedness too, groomed beard but slightly unkempt long hair, traditional garb and courtly behaviour, as well as poetry, that he could be shown without being named.

‘Jigar’ is seen as the last standard-bearer of the classical ghazal, or the ghazal’s classical tradition, but was rather a ‘bridge’, between its highpoint in the mid-19th century and its transition to the 20th century and beyond.

He was also a connecting link between Urdu poetry and its widening social reach as the dialogue the character utters shows – and is followed by him encouraging Dutt to continue:

“Tum kuch keh rahe the, barkhurdar. Chup kyun ho gaye. Kaho, kaho..”

Jigar Moradabadi – Real Life

This was true in real life too – a young Jigar took instruction from Nawab Mirza Khan ‘Dagh Dehlvi’ – who had participated in mushairas with Ghalib and Zauq – and himself later, mentored poets like Asrar-ul-Hasan Khan ‘Majrooh Sultanpuri’, Jan Nisar Akhtar, and others.

And then like many contemporaries, he did not write for films, yet his work willy-nilly figured in them. While “Kaam aakhir jazba-e-beikhtiyar aa hi gaya/Dil kuch is surat se tadpa unko pyaar aa hi gaya” was used in ‘Pyaasa’, in ‘Daag’ (1952), the Hasrat Jaipuri-written “Ham dard ke maaron ka, itna hi fasana hai/Peene ko sharaab-e-gam, dil gam ka nishana hai” seemed inspired by his “Ham ishq ke maaron ka itna hi fasana hai/Rone ko nahi koi hasne ko zamana hai”.

Then, ‘Be-Raham’ (1980) used this sher – along with most of its ghazal which begins: “Ik lafz-e-mohabbat ka adna yeh fasana hai/Simte to dil-e-aashiq phaile to zamaana hai”. Another master sher in this is “Yeh ishq nahi aasan itna hi samajh lijiye/Ek aag ka darya hai aur dub ke jaana hai.”

Before that, Shyam Benegal’s ‘Junoon’ (1979), the 1857 drama starring Shashi Kapoor, used his ghazal, “Ishq ne todi sar par qayamat.”

How Jigar’s Prime Couplets became popular in films?

But, the prime example was how the prime couplet of ‘Jigar’ became most known to film buffs after actor Raj Kumar made it a dialogue, delivered in his bombastic, drawling style: “Ham ko mita sake yeh zamaane mein dam nahi/Ham se zamana khud hai zamaane se ham nahi.”

Born in April 1890 in Moradabad, ‘Jigar’ was the son of Syed Ali Nazar, who worked in the Law Department and was inclined to poetry too, being a disciple of Khwaja ‘Wazir Lakhnavi’.

After elementary education, including in English, he worked as a salesman for a local spectacles dealer. Later, he turned to poetry full-time, settling in the town of Gonda, where he found in noted poet Asghar Hussain ‘Asghar Gondvi’ a mentor of sorts. He was a familiar face in mushairas all over the country till the mid-1950s, when he began slightly distancing himself from shayri, ahead of his death in September 1960.

‘Jigar’, as mentioned, was a paladin of the classical tradition, and as such, his shayri usually dwelt on love and other facets of the human condition. As he said:

“Un ka jo farz hai vo ahl-e-siyasat jaane/Mera paigham hai mohabbat jahan tak pahunche.”

Yet, while he used the usual tropes associated with the topic, he imparted his own stamp on them with his own stylistic variations.

One of these was paradox. Take:

“Atish-e-ishq woh jahannum hai/Jis mein firdaus ke nazaare hai”, or “Kamaal-e-tishnagi hi se bujha lete hai pyaas apni/Isi tapte huye sahra ko ham darya samajhte hai”, or even “Mohabbat mein yeh kya maqam aa rahe hai/Ki manzil pe hai aur chale jaa rahe hai” and “Usi ko kehte hai jannat usi ko dozakh bhi/Woh zindagi jo haseenon ke darmiya guzre”.

“Abad agar dil na ho to barbad kijiye/Gulshan na ban sake to bayaban banaiye” is another example.

Then, ‘Jigar’ frequently resorted to some deft wordplay and situations: “Tere jamaal ki tasveer khinch doon lekin/Zabaan mein aankh nahi aankh mein zabaan nahi”, “Suna hai hashr mein aankh use be-parda dekhegi/Mujhe dar hai na tauheen-e-jamal-e-yaar ho jaaye”, and “Aghaaz-e-mohabbat ka anjaam bas itna hai/Jab dil mein tamanna thi ab dil hi tamanna hai.”

Vivid imagery was another strength: “Baithe huye raqeeb hai dilbar ke aas-paas/Kaaton ka hai hujum gul-e-tar ke aas-paas” and “Har taraf chaa gaye paigham-e-mohabbat ban kar/Mujh se achhi rahi qismat mere afsanon ki.”

And ‘Jigar’ could use rhetorical devices, like repetition to good effect, as in: “Dil hai kadmon par kisi ke sar jhuka ho ya na ho/Bandagi to apni fitrat hai Khuda ho ya na ho”, “Kabhi un mad-bhari aankho se piya tha ik jaam/Aaj tak hosh nahi, hosh nahi, hosh nai” and sometimes, alliteration: “Hai re majbooriyan mahroomiyan nakaamiyan/Ishq aakhi ishq hai tum kya karo ham kya karen.”

At other times, he could be engagingly simple: “Garche ahl-e-sharab hain ham log/Yeh na samjho kharab hain ham log”, or “Pehle sharab zeesht thi ab zeesht hai sharab/Koi pila raha hai piye ja raha hoon main.”

And a philosophical outlook can always be discerned. It may be active like: “Kya husn ne samjha hai kya ishq ne jaana hai/Ham khaak-nashinon ki thokar mein zamana hai” and “Apna zamana aap banate hai ahl-e-dil/Ham vo nahi jin ko zamana bana gaya”, or a bit resigned: “Jo un pe guzarti hai kis ne use jaana hai/Apni hi musibat hai apna hi fasaana hai”, “Maut kya ek lafz-e-bemaani/Jisko mara hayat ne maara”, and “Yeh misraa kaash naqsh-e-har-dar-o-deewar ho jaaye/Jise jina ho marne ke liye taiyar ho jaaye.”

There is much more to enjoy in the extensive corpus of ‘Jigar’, whose own epitaph could be: “Hami hab na honge to kya rang-e-mahfil/Kise dekh kar aap sharmaiyega.”

source: http://www.ummid.com / Ummid.com / Home> International / by Vikas Datta / IANS / April 16th, 2023