Mehmoodabad (Sitapur District), UTTAR PRADESH :

It is a formidable lineage. And the huge responsibility must wear heavy on the elegant shoulders of the suave and articulate, Cambridge educated Raja of Mehmoodabad. Farzana Behram Contractor comes away a fan of the Raja – Amir Mohammad Khan, Suleiman to friends.

We all have days in our lives we count as memorable. Spending a day in the life of the Raja of Mehmoodabad is one such in mine. It was special because I saw a part of life so removed from the ordinary, yet so similar because of the simplicity and warmth lent to it by a human being who is nothing if not extraordinary.

I suppose all the questions I asked– and I asked questions all day long, sent the Raja of Mehmoodabad on a trip to nostalgia. He spoke non-stop, till he was hoarse by nightfall. It was for him, an emotional journey. Let me recount it for you.

I was chatting with all the chefs, while at breakfast at The Sahib Cafe of the beautiful Taj Residency where I was staying. I had already received the message from the Reception – the Raja had called to say ‘he would be five minutes late, please bear with him.’ Five minutes! And he called to say that!

Within minutes I heard a gentle, soft-spot spoken, enquiring voice, “You are Farzana.” I looked up and he continued, “I am Suleiman, sorry I got a bit late.” Flustered, I sprang to my feet. I was expecting the chauffeur to come fetch me, not the Raja himself! Talk about the Lucknow tehzeeb. It’s so humbling. As we walked to his jeep he said smilingly that he had done his ‘due diligence’ on me. Checked me up on the net and therefore recognized me in the restaurant. Phew, long live the internet.

We started to drive towards Mehmoodabad, the Raja’s erstwhile principality. We were going to eat lunch at his mahal, which I was really looking forward to. I had heard that there were none better than the khansamas at his palace. Cruising along rural Lucknow was new to me. And I found the sights rather pleasant. It was already so relaxing.

“Tell me about your family…” I began, and the first thing the Raja said, rather strangely, was, “My father was fond of itr(attar), though within limits. We had our own itr unit, never ever bought any from the market except occasionally some which was made in Mehmoodabad. There is a special method of processing it, so as not to lose its scent. Silver pot, silver ladle.” And he went quiet for a while. I got the feeling he began to speak about his father in association with fragrance because he may have got a whiff of him in his mind. Happens you know, when you are very close to someone, you remember their personal smell, long after they are gone.

His father, Raja Amir Ahmad Khan was a special man, to his son as well as to a multitude of people. He was known as Raja Sahib of Mehmoodabad. He was born in 1914 and was educated in Lucknow and later in England. Raja Sahib’s father Maharaja Sir Mohammad Ali Mohammad Khan (1877-1931), was a great landowner of Uttar Pradesh and a trusted friend of Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

Raja Sahib succeeded to the estate of Mehmoodabad on March 23, 1931, on his father’s death. At that time Mehmoodabad was one of the richest estates of the Awadh. He was keenly interested in the Muslim renaissance and associated himself with the Muslim League at an early age. He was at one time the youngest member of the Working Committee of the All-India Muslim League. In 1937, he formed the All-India Muslim Students Federation, which mobilized the Muslim Youth for the cause of Islam. It soon became the vanguard of the Pakistan Movement.

Raja Amir Ahmad Khan also served as Honorary Treasurer of the League for several years. He was a puritan and ascetic in personal life and placed all his wealth and ancestral estate at the disposal of Muslim League.

Disillusioned by the political turmoil in the country in the wake of the Independence struggle, he migrated to Iraq. From there, much after Independence, he went to live in Pakistan. Subsequently he settled in London where he remained Director of the Islamic Culture Centre until he died on October 14, 1973 in London. He was buried at Mashhad in Iran.

“The late Raja of Mehmoodabad, Raja Amir Ahmad Khan, was a worthy member of the long line of Maharajas of Mehmoodabad. The family took part in the uprising of 1857 for which it was punished with confiscation of a large part of its estate.” This is what Indira Gandhi had to say about his father in 1984 in a book entitled The Life and Times of Raja Sahib of Mehmoodabad by Syed Ishtiaq Hussain. In 1965, the same fate was to recur.

A very rich ancestry for the present Raja. “Yes, I feel humbled by my ancestors. They were at the highest levels of civilization. They were poets, writers, educationists, men of letters who possessed a strong spirit of enquiry. The responsibility is enormous. Especially the moral legacy,” pondered the Raja. And then continued, mysteriously smiling at some thoughts that went through his mind, “My father was wonderful. He studied at La Martiniere and then had private tuitions. He was like a son to Jinnah, who told him, ‘I will be your university’. It was my grandfather who conducted the marriage of Jinnah and Ruttie. One, an Isnasari, the other a Parsi. They went to Metropole for their honeymoon!” Metropole, incidentally is a hotel in Nainital owned by the Mehmoodabad royals.

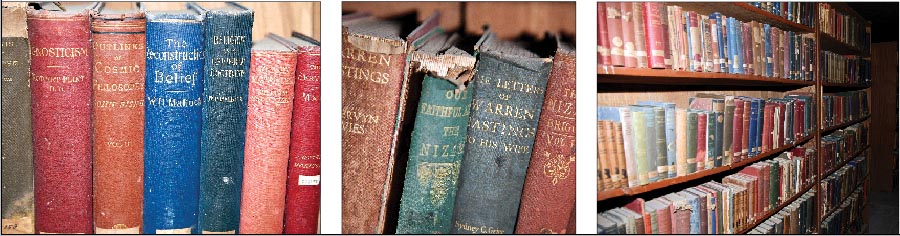

“Father was deeply involved in Pakistan’s struggle. Nehru and our family go back to Motilal days when my father, 22 years old and an idealist, became a member of the National Party. He was committed to the Islamic Cause, but was getting disillusioned by and by. He was shattered when the great slaughter took place and realized how mistaken they were in their assessments. He was saddened seeing the lust for money, property and power which were destroying human values. In 1945 when he exiled himself to Iraq, he took his family, cooks, servants and the library and built himself a house and stayed on till 1957 when he shifted to Pakistan. He was a real scholar, a poet, a writer, both secular and religious. He spoke Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Hindi, Sanskrit and French.”

Speaking of his own involvement in politics, the Raja said, “I wanted to serve the country. Rajiv Gandhi chose me to stand from Mehmoodabad. I won the election in ’85 when the Congress came to power and again in ’89 when it did not. But when they wanted me to stand for a third term I declined. I was unhappy. I did not leave the party, just faded away, so to say. To be religious which I am, is not a bad thing. But to use it as an instrument to attain political power is not what I stand for. It involves lies, corruption. By ’91, I saw no more proof was needed, catastrophe in the country was imminent. There was communalisation of politics, criminalisation of politics, commercialisation of politics. Politics became a transaction! When I was an MLA, I toured a lot in the state and I see no quantum difference between ’85 and now. There is destruction of environment, all this monstrosity, who is responsible for it? Where is the prosperity in rural life, it is hardly noticeable.” He turned to the driver and enquired, “Kya farkh hua hai?” “Koi nahi, Sahib,” the driver replied, earnestly.

The Raja looked visibly disturbed. We know how the political system works in our country; ‘enrich our own selves’, ‘exploit caste’, ‘play the communal card’, I could hardly visualise someone with his kind of sensibility surviving it. I quickly changed the subject, “What about your mother?” “Oh!” exclaimed. “She was a gem. A very moral lady, she passed away in ’91. My wife Vijaya (the pretty daughter of Former Foreign Secretary, Jagat Mehta), was very close to her. She was a Rani in her own right. Rani Kaniz Abib of Belahra. She had no brothers and so succeeded her father. She was in purdah, but highly educated and she was very interested in my education. She always said, ‘Nothing will remain except education. That will be with you, forever in this transient life’,” he trailed off.

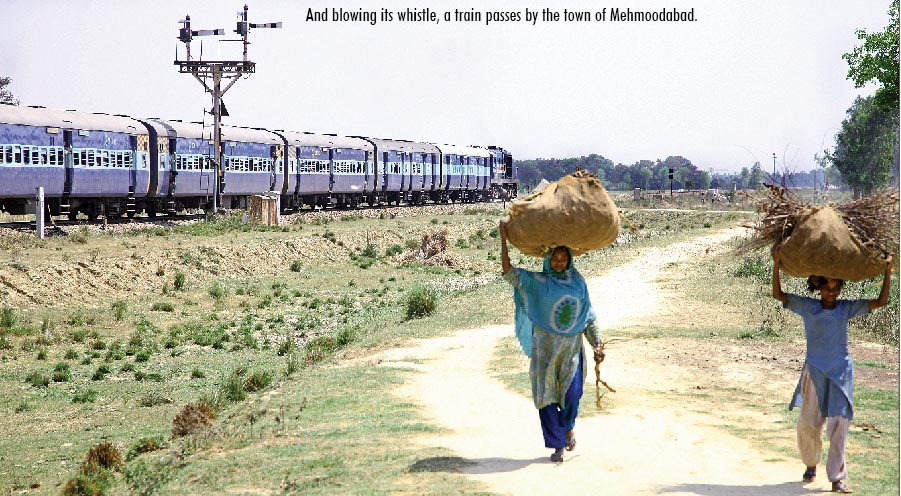

We were now approaching Mehmoodabad. And I was happy we were stopped by the red light at the railway crossing. It’s been a while since I had a chance to see the signal drop, watch a train pass by. I hopped out of the air-conditioned comfort to feel the warm air outside, walk on mud, look at the local people, shoot some pictures, hear the whistle blow, to know it was all clear and we could drive on through the metal gates. The small, forgotten pleasures of childhood come alive in such places.

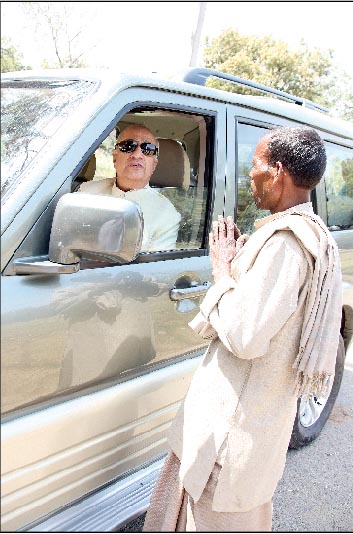

Well, soon we entered the town of Mehmoodabad. Driving through the straight but narrow and crowded lane I saw people fold their hands together in a namaste when they saw the Raja’s vehicle. Some bowed in greeting, some raised their hands to their foreheads, yet others placed them on their heart. And in response the Raja kept doing an aadaab, nodding ever so slightly. It was touching. To them he is still their king. When I was foolish enough to make a passing comment about them being subjects once upon a time, he retorted, “We are all subjects of God, how dare we call them our subjects. And we are not subjects; we are all children of God.”

And so we discussed the subject of God and nature. “There is so much you take in faith. Though science is a deterministic theory it does not have all the answers related to life. Solace, grief, love. Two people look at the same thing differently. The beauty of the world is in its difference. Look at the diversity in nature, it’s beautiful. Look at the rainforest, each lives in its own niche.” I let him carry on, it was nice listening to him.“Love of God is first love of man. From there you go stage by stage. In every suffering God suffers with you, although you are his creature. He has a resonance. There is no answer to that. It transcends human rationality. Humari taqleef mein Allah ki tasbi hai. He is one whose name is itself a curative and whose remembrance itself cures one…” When I asked him if he prayed regularly, he answered, “Subject to my communication with God, that day. Sometimes I have a fight with him, like a child sticking his tongue at his mother, I sulk. But it’s a constant remembrance not of God only but of Him through his creations.

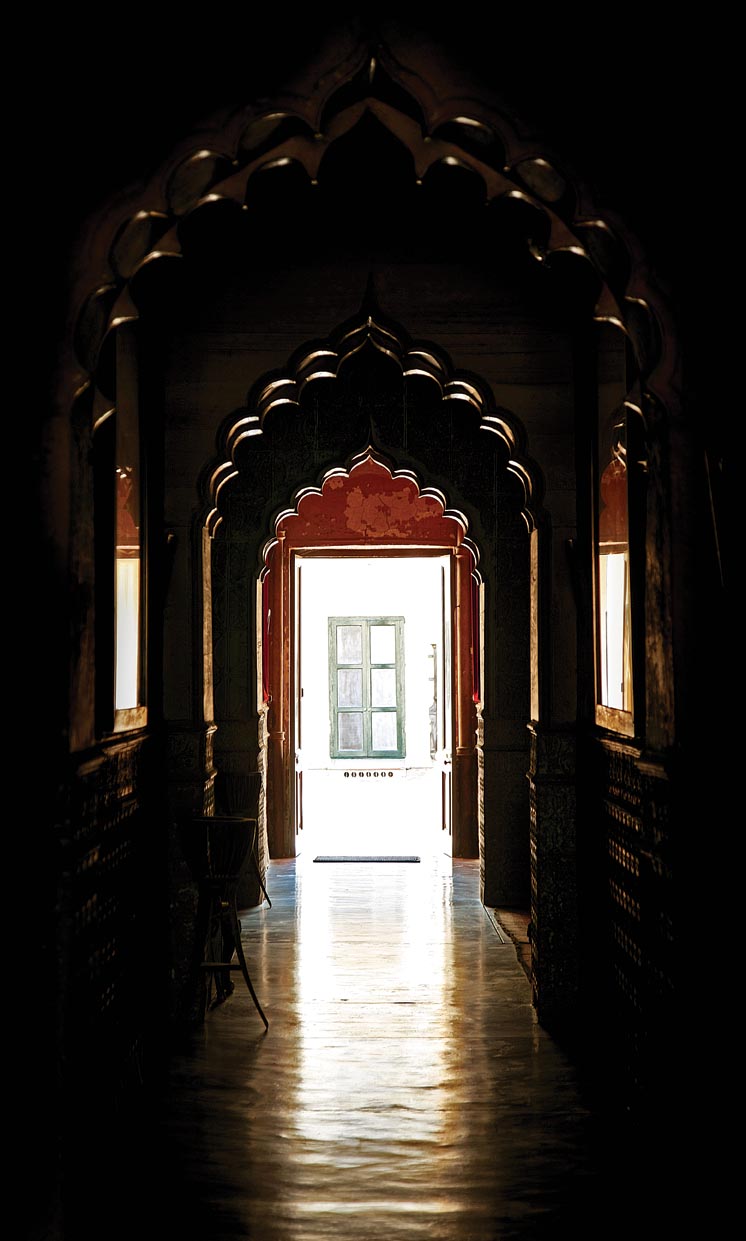

The gates of the palace were now in front of us. Nothing spectacular, on either side vendors had usurped the space. One of them was selling beautiful earthen pots, surais they are called. We drove through the vast driveway which had old mango trees spread out over the grounds. There was no pomp, no ceremony. It was apparent to me by now that the Raja, a tech-savvy, reserved, low profile man, is an intellectual who lives in the real world in an unfussy manner. He is someone who can stand in a queue for movie tickets, can and even does earn a living the honest way. He is an occasional professor of astrophysics at Imperial College, London, and the Instituteof Astronomy at Cambridge University, from where he had earlier done his mathematical tripos. “Mathematics,” he said to me, “is a language. There is such beauty in it.” I didn’t dare tell him at the time that I knew zilch about math and hated it the most at school.

But here I was now, admiring beauty of another kind. The architectural one. The first thought that hit me as I stood watching the palace in front of me was: What a shame that all this was snatched away from the rightful owners and kept locked away for the longest period of time! I felt a surge of anger that such a monumental place was kept in a state of neglect, that it was allowed to go to seed! It is common knowledge that a vast amount of property owned by the royal family was impounded in 1965 by the government, as ‘Custodian Enemy Property’ – all because his father lived in Pakistan at the time.

After a tour of the entire place (the Library has thousands and thousands of rare books), I requested the Raja to tell me about the horrible truth and his feelings now that he had won the 32 year long legal battle and got back all his properties spread over not just Mehmoodabad, but Lucknow, Sitapur, Lakhimpur Kheri and Barabanki districts in UP and Nainital in Uttarakhand: the impressive Butler Palace and the Metropole, among others. “In 1965 when the war with Pakistan began, overnight they took over all our property. Surrounded it and sealed it. I was at Cambridge, at Pemberly then, and I was shattered. News didn’t get through so easily in those days. There were seals on every lock. When the Qila (that’s how he refers to the palace) was opened after one and a half years and conditional access was given to us, it was found that things were missing. A hundred quintals of silver, crystal, what not. My mother’s embroidered clothes were burnt just to extract the silver and gold embroidered in them. There was deep sadness in the family. We continued to battle, struggling against anger and depression. Eventually and only recently, we got all our properties back. But it will be a long haul before we sort out the complicated affair, for many properties have passed on to the third and fourth line of owners. What can I say; my friends had warned me that it was going to be a can of worms. But I felt that it was a can worth opening.”

I couldn’t agree more. It will baffle the reader to know that this property we are talking about is valued at thousands of crores of rupees. Half of the prime structures in upscale Hazratganj and Jopling Road which include Butler Palace and its lake are part of his ancestral property. When you view this injustice and unfair play against the backdrop of what this family has contributed, it is all the more disturbing. His great, great grandfather Raja Nawab Ali Khan-Muqeem ud Daula’s contribution to the first war of independence is recorded even in Surendranath Sen’s official history of the uprising brought out by the Information and Broadcasting Ministry during the centenary year in 1957. His grandfather was the first Vice-Chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University, an institution he helped set up.

“My family contributed so much to the country – Lucknow University, King George Medical College, Amir Daula Library and so many premier educational institutions. In fact, my great grandfather set up a school in Mehmoodabad way back in 1885. And here I was struggling year after year to fight a mindset which saw us as traitors,” said the Raja and added with a sigh, “But finally it is all over now.

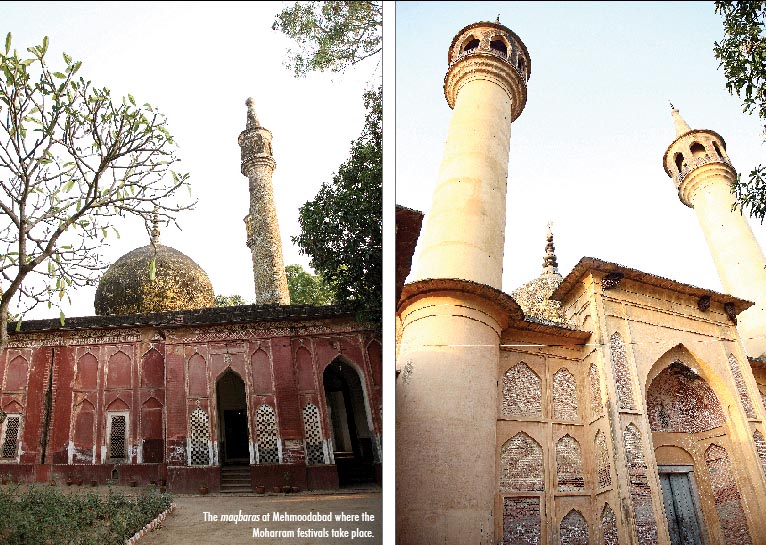

Lunch was announced. We walked through many halls to reach the dining room. Restoration work is an ongoing task, and beneath all the dust lay much beauty. I couldn’t help thinking what a beautiful hotel this Qila would make. The Raja makes only occasional visits here. But always during Moharram and Ramzan, to perform the many religious rituals that take place every year.

At lunch we discussed food. “Raja Sahib, my father, was very aware of the hunger and poverty around him and he was influenced by the finer teachings of the Caliphs. He was governed by, ‘no morsel you take is free from the hunger of another person’. But while he was always conscious of that fact, he was also gifted with discerning taste buds. He could and did appreciate the quality, fragrance and delicacy of the food cooked at home. But he could also deny himself the pleasures and often did.”

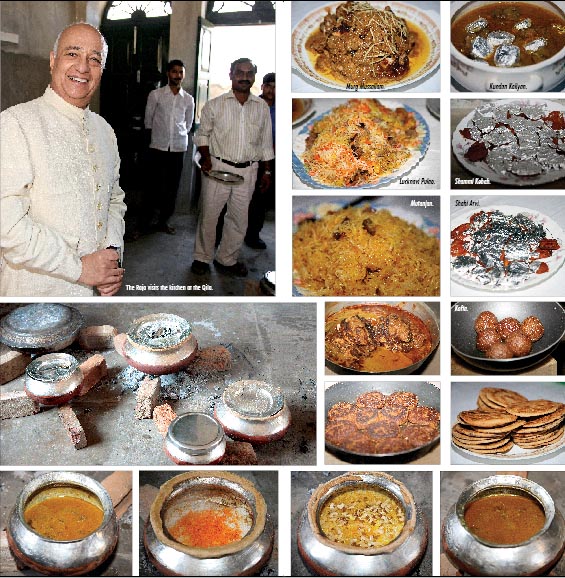

“We had a battery of cooks, all male. I remember three names, Hazari, Behraiji and Rasheed. Under them were many younger ones. Some from their families are still serving us. None of my ancestors drank, but served wines and liqueurs, with great finesse.They were not bigots, but would also make sure they did not affect the sensibilities of the orthodox. I personally never paid much attention to food. It was an ordeal to get through. One couldn’t eat what one wanted and vice versa. But everything was always cooked at home, including the breads. Kulcha, sheermal, taftane… Describing how food would be sent to his father wherever he was, he said, “Food was prepared and placed in a large octagonal container, with a seenee over it and then covered with shaal baat, a red cloth. The chamberlain would put his stamp on it and then send it to wherever my father was. It was carried on a khasa, on the server’s head. Ah, what a ceremony. At other times there would be a takht, a dwasterkhan, where the chamberlain would sit in the middle of the takht and pass things around, asking for comments!”

If the chamberlain was still around I would have thumped him on the back, the food I ate at the Qila was so exquisite. In his absence, I went looking for the cooks, found them in the kitchen with the last of the dying embers in the log and brick stoves and told them “Shabash, bahut acha pakaya aap sab ne, shukriya.” It went down well, but not enough for them to part with the mutanjan recipe I wanted. Instead very courteously they invited me to come again! “Phir zaroor aaye,” they said to me respectfully, not looking up.

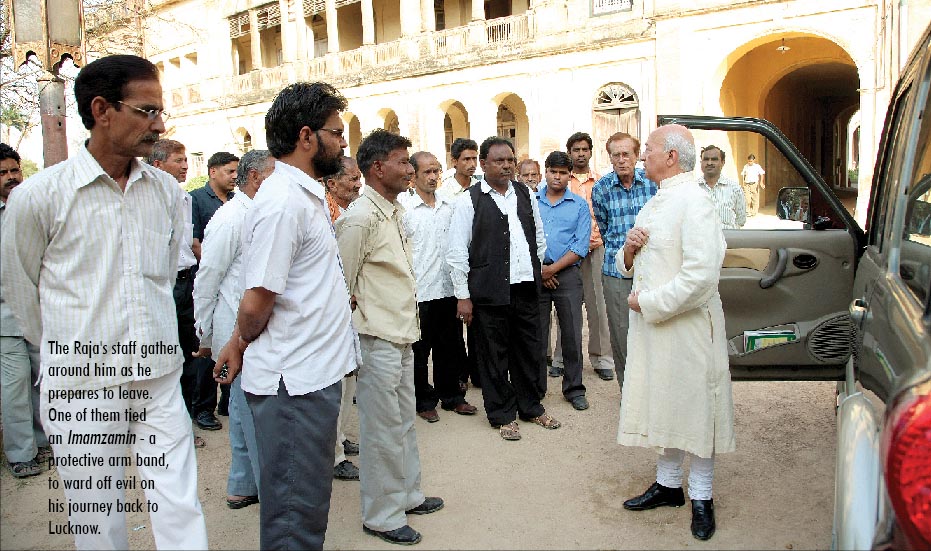

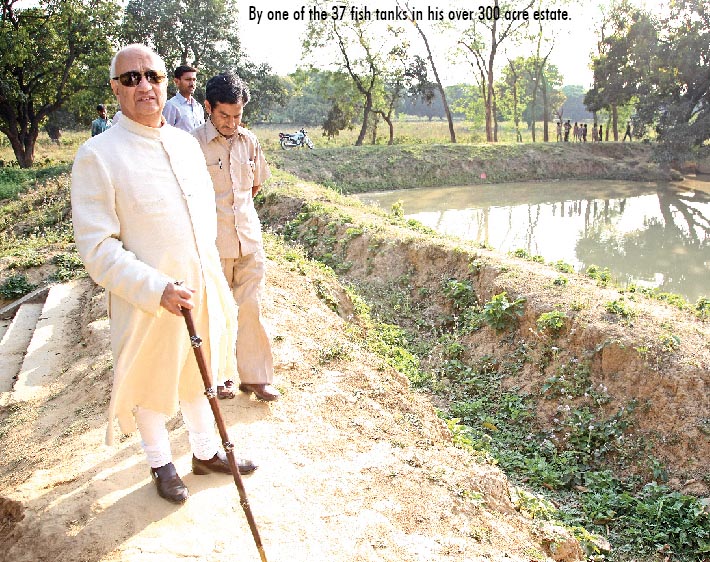

Soon it was time to leave, but not for Lucknow. We were first going to drive around the Raja’s fields. Just 300 acres! And we were not doing it for my sake as much as to listen to the tales of woe of his people and to check what was happening on his land. So we went and visited a group of cowherds and then walked alongside one of the 37 fish tanks (not your aquarium variety, but massive ones where his staff is breeding fish), we checked out a ‘party spot’ where marquees had been set up many decades ago, when the servants of the house wished to give the young Raja a farewell treat when he was going away to school (they made pastries which he was so fond of), and lastly we landed up at a field where mustard was being threshed. This was a historic moment of sorts. It was the first crop grown in over 35 years since the Government take over. The Raja of Mehmoodabad emotionally said a dua over the small wicker daliya full of tiny mustard seeds that the farmers presented to him. Later he chewed on a few of these tiny seeds and declared, “The mustard doesn’t taste so good, but it will improve.” He is like that – honest and egoless.

We were now driving back, but via Belahra, in memory of his mother. Her palace was charming. Looking at it and with my usual forthrightness, I blurted “This will make an even better hotel; there is so much character here.” The Raja merely smiled, but I got the feeling it may just about happen. His sons Ali and Amir may do so.

Our last halt was Dewa Sharif. A sufi durgah. We stopped to pay our respects. The smell of roses at the shrine was so dominant. My parents often used to visit this shrine and I have a faint recollection of being taken there as a child. I remember distinctly, the mitti ke bartan – tiny mud utensils we used to play with on our holidays in Lucknow. They were a speciality of this place. Meandering through the lane that leads to the durgah, I chanced upon a shop selling these. I was so delighted. Life always comes full circle.

The Raja of Mehmoodabad, Amir Mohammad Khan, who was now Suleiman to me, thanked me for a nice day as he dropped me back at the Taj, before driving off to Mehmoodabad House in Qaiserbagh, his home in Lucknow. It is I who would like to thank him. For a peek into history, for an insight into his private life and for showing me what grace and graciousness and true old world charm are all about. replica cartier, replica cartier watches, , womens cartier watches.

source: http://www.uppercrustindia.com / Upper Crust / Home / by Farzana Behram Contractor / July-Sept 2015 issue