hennai, TAMIL NADU :

As part of the Madras Week, S. Anwar throws light on the chronograms etched in mosques across the city.

When Saadathullah Khan, the new Nawab of Arcot created a beautiful garden in his capital city Arcot, and was looking for a suitable name, Jaswant Rai, his chronicler presented him with the name ‘Humayun Bagh,’ meaning ‘Auspicious Garden.’ The Nawab was very impressed and mighty pleased as he also understood that his chronicler had offered him much more than a name.

Earlier the Nawab had gone to great lengths in adorning Arcot with stately buildings. What was missing was the gardens. Being a Mughal protégé, the Garden was important. And so next to the river he laid an extensive garden with flower beds and fruit bearing trees of different kinds. He further decorated it with one hundred and fifty fountains that were perennially fed by a system of waterworks.

Keeping the climatic conditions of Arcot in mind the Nawab ordered for trees from Telengana to be planted in the garden. Once the work was done, he was equally keen to have a worthy name for his royal garden. That was when Jaswant Rai pleased him not just with a name but a skilfully composed ‘Chronogram’ which, when carefully read, also revealed the year of its (Garden) creation in the Islamic calendar of Hijri as 1,113 (corresponds to 1,701 CE).

Before the Indo-Arab numerals came into wide use, it was common to assign numerical value to alphabets as the Greeks did. Chronograms essentially took it one step further where the numerical value assigned to each letter in the text when added, the sum total reflected the year of the event on which the chronogram is composed. Essentially the word “Chronogram” meant “time writing,” derived from the Greek words chronos (“time”) and gramma (“letter”).

Typically the chronograms could be just one word, a verse or verses including those from the Holy Scriptures of any of the Abrahamite religions. The Jews composed chronograms using Hebrew numerical system and it was known as Gematria. The Abjad system assigns numerical value to the Arabic letters and it is common to see the important Islamic phrase, a phrase with which Muslims begin their prayer or any good deed – ‘Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim’ (“In the name of Allah, the most merciful, the most compassionate”) – with a numeric value of 786.

Though this tradition of composing chronograms was prevalent among various societies, it came into its own during the medieval period with the Jews, Christians and Muslims taking to composing ‘chronograms’ to commemorate events. It could be a victory of an army, inauguration of a palace, a church, a mosque or could be even death.

When Begum Sahiba, the Nawab’s companion of many years, died during the month of Muharram, many a poet in Saadathullah Khan’s court wrote elegies and as was the tradition some of them attempted composing chronograms. The most appropriate one was of course composed by the Nawab’s elder brother Ghulam Ali Khan. It was a verse from the Holy Quran, Wadhkhuli Jannati (“And enter my Paradise”). It gave the year of her death as 1114 Hijri era, which in Gregorian calendar translates to 1702 CE.

A year after her death the Nawab built another garden of the same dimension as the Humayun Bagh. Jaswant Rai called the new garden the ‘Nau Jahan Bagh,’ which when read as a chronogram, revealed the year of opening the garden as 1115 A.H (corresponds to 1703 CE)

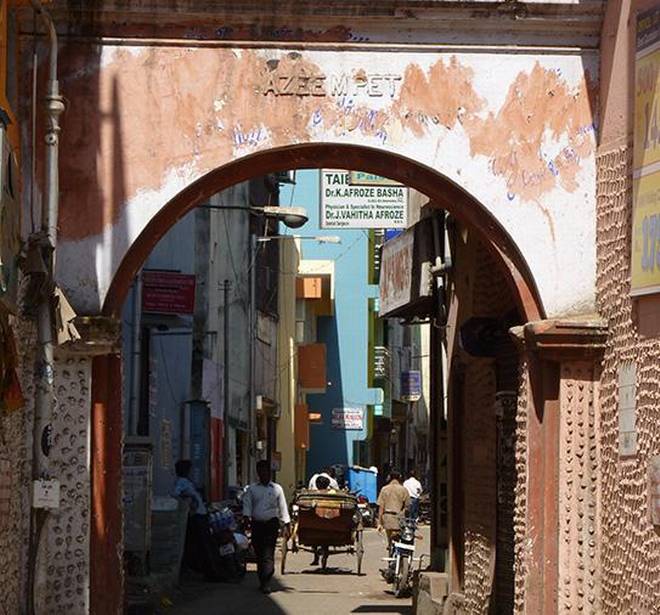

In Madras, we do have a number of mosques that have their year of construction beautifully camouflaged in chronograms. Nawab Muhammad Ali Walajah, another celebrated Nawab of Arcot, was equally known for his liberal donations cutting across religions. The Kapaleeswarar temple tank at Mylapore was his donation. He moved the court to Madras and built a palace for himself at Chepauk. When the Muslim merchants of George Town approached him for a mosque, he built the Masjid-e-Mamoor mosque for them on Angappa Naicken Street. From the chronogram composed in Persian and inscribed inside the mosque, it is understood to have been constructed in the Hijri year 1199, which corresponds to 1784 CE.

A little later when the Nawab wanted to build a Big Mosque in Triplicane, nearer to his palace at Chepauk, he held a competition for the best chronogram to be inscribed. Interestingly it was won by Raja Makhan Lal Khirad, a Hindu who was a munshi and in the employment of the Nawab. His chronogram, ‘Dhikrullahi Akbar’ (Remembrance of God is great) is inscribed above the Mihrab (a semicircular niche in the wall of the mosque that indicates the qibla; that is, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca and hence the direction that Muslims should face when praying) and gives us the year of construction as 1209 Hijri which translates to 1794 CE.

These are just a few examples of the many chronograms that dot our landscape. The chronograms of the Arcot Nawabs were not just about the art of writing time but also a reminder of our secular past we can be rightfully proud about.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Friday Review / by Kombai S. Anwar / August 25th, 2016