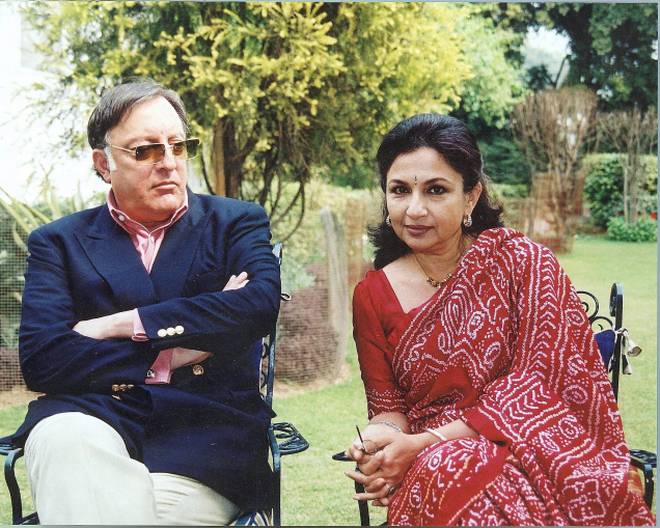

Cricket, cinema and royalty — can there be a more potent mixture? Three decades after he headed the Indian cricket team with such distinction and his begum won the hearts of cinegoers, the spell cast by the couple continues. The Pataudis — Mansur Ali Khan and Sharmila Tagore — embody the Indian dream of gracious living and togetherness. You realise why when you meet them at their spacious bungalow in Delhi.

Though his clipped replies on the telephone make you apprehensive about the interview, he is quite forthcoming when you begin to talk to him. “I know what it is like to be at the other side for I was a reporter for the Ananda Bazaar Patrika many years ago,” he says. He listens to the questions with patience and courtesy. To be a Nawab is to be heir to a lifestyle marked by refinement in speech and behaviour.

How does it feel to be so respected three decades after leaving the game and how much has the royal aura contributed to this, you ask.

“If there is respect, it is because of a mixture of many things,” he replies. “It is also because I married into a recognised family (Sharmila is a grand niece of Rabindranath Tagore) with cultural interests and a literary background. There is a lot of curiosity (about us).

“I was not the only one in cricket from a similar background,” he says. “There were others like me — Hanumant Singh, Inderjit Singh, Fatesingh Gaekwad (who was President of the Board of Cricket Control), the Maharaja of Udaipur, the Patiala family… there were a lot of us around. The disadvantage was not because of the background but because I did not understand the undercurrents; I had not studied in India but abroad. It helped too for I did not get involved in the local politics. Regarding the royal aura, you are right in the sense we didn’t indulge in nepotism or favouritism. We played it pretty straight — not promoting someone because he was from a particular background. I played most of my cricket from the South. I still meet Chandrasekhar, Prasanna and Ramnarayan.”

What are his links now with Pataudi, the princely State in Haryana?

“Links are with the people, not with the soil, After Independence, there was a large transfer of property. Quite a few people from Pataudi migrated to Pakistan. Many of my family members too went away, like my uncle, a former army general in Pakistan, who has written a book about the family and its history.”

Does he visit often and how much regard is there now in Pataudi for the former royal family?

“I’m a fairly private person. I don’t make an issue of going there. But for certain occasions, I do go. A large number of people came to my mother’s funeral to pay their respects. So the connection is still there, the bond is strong. I’m not into politics in Pataudi. I do some social work and am involved in running an eye hospital.”

What are his earliest memories?

“The background for me is cricket or sport. The earliest memories are of playing cricket on the lawns of our home and at the Roshanara Club at the age of nine.”

As for the story that he was upset when his father, the renowned cricketer, Ifthikar Ali Khan, stepped in and took a catch, he says, “Oh, that! I was young and father thought I would drop it.” He adds with feeling, “His was a very good presence.”

“My first coach was Sir Frank Worrell,” says the Nawab who became the youngest captain in the world at the age of 21 and acquired the appellation “Tiger” for his superb fielding skills. “My Master at Winchester College (in England where I did my school) also coached me. Winchester was an important turning point. My son Saif also went there, but perhaps,” he adds reflectively, “it is better to go abroad to study when you are a little older.”

Does he regret not playing one-day cricket as he would have been eminently suited for it?

“Yes. But I’m happy I played for my country. Nobody thought that one-day cricket would become so popular. When we played, there was not much money in the game but we enjoyed our game very much. And no, I don’t watch all the matches whether the World Cup or others. I was a commentator for AIR and Doordarshan. The main activity however had to be cricket or commentary — we had to be totally committed to the game.”

Is he disappointed his son Saif did not become a cricketer but an actor?

“Not at all, there was no compulsion for him to be one. I’m very happy that he is happy.”

Did not the commercials on television and the advertisements in print contribute to keeping the Pataudis in the public eye, projecting them in a regal way?

“If I came across well, it was because of the directors of the commercials,” he states simply.

Having been educated in England, did he not want to settle there?

“I feel very comfortable living here. My forefathers came here from Afghanistan during the time of the Lodis and established themselves after Aurangazeb died. Pataudi was set up as a principality by the English.

How difficult is to maintain the property?

“I have no palace. Palaces are like elephants around your neck. They are very difficult to maintain. Part of the Bhopal Palace has been given to a University. My cousins live in the other portions. My father sold the house in Delhi and built the palace at Pataudi for my mother when they got married in 1938. My mother was recognised as the Begum in 1968. Her elder sister migrated to Pakistan and her son, my cousin, was the manager of the Pakistan cricket team in this World Cup.”

With paternal ancestors at Pataudi and the maternal inheritance of Bhopal, life must have been interesting for him as a child…

“It was. Bhopal was a State with a great deal of protocol. There were bodyguards. When we had to meet our grandfather, we had to wear our best clothes and we were then lined up before him. He would ask: `How’s school? Which class are you in?’ We would answer, bow and come away. Pataudi was different — there were no bodyguards and life was more informal.”

Is not the present trend in the country — of religious fanaticism — disturbing?

“Extremely. But it is inevitable, a post-colonial syndrome which the country has to go through. Moderate voices won’t be heard for a lot of propaganda has been unleashed. It reflects poor thinking and vision, as there are more important things to think of — building houses and providing drinking water. There is so much of unemployment and frustration.”

What does he have to say about his foray into politics?

“I was in politics in 1992, when Rajiv (Gandhi) said `we would like you to come into it’. If he was alive, I might have still been in politics though I find it claustrophobic as it robs you of privacy.”

And how does he spend time now?

“Talking to reporters,” he deadpans.

* * *

“WHAT’S in a name?” asks Sharmila Tagore, acclaimed actress and the Begum of Pataudi, when you talk to her. “To elderly family members and friends, I am the Begum. I’m Rinku to my friends and Mrs. Khan to others. I’m better known as Sharmila Tagore. That’s what I am, what I have made of myself. I come from a middle-class literary background and I don’t have an identity crisis.”

“Belonging to a royal family is not an advantage any more in India,” adds the Begum.

“Titles are no longer respected. The tendency is to minimise their worth whereas titled people are respected in England.

“The reaction here comes from a very uninformed source and is a response to the reading of novels, which depict the royals as debauched and autocratic. The books do not highlight how the former rulers maintained law and order. Bhopal did not lose a single life in riots during Partition. The rulers provided good administration. They still have a place in the hearts of the people and are invited to grace marriages and other functions. Jealousy prompts some people to look down on them. But they can’t help but be impressed by royalty.”

Has she had to give up anything — freedom for instance — by marrying the Nawab?

“I haven’t given up anything. He is very liberal in his views. I’ve gained a lot of experience and gained another culture, cuisine, and way of dressing. I’ve benefited a lot.”

As an outstanding example of a successful Hindu-Muslim marriage, would it not be a good idea for them to make efforts to promote communal harmony?

“Pluralism is the strength of our country. History has shown us that we can co-exist peacefully. India absorbed other cultures but now we are becoming xenophobic. We are reacting 500 years after the Moghuls came. But if Tiger and I make attempts to promote harmony, I do not know how far we will succeed. People will say that I am not a Muslim and that Tiger is a Hindu fanatic.”

How do her two daughters, Saba and Soha, and son regard their lineage?

“Saif is very much into family history and all three children are conscious of their ancestry but in a nice way.”

Cricket lofted it

FIVE HUNDRED years ago, Mansur Ali Khan’s ancestors came from Afghanistan, equipped with superb skills in horsemanship, and looking for greener pastures. Salamat Khan, his forefather arrived in India in 1480 A.D. with his clan during the time of Bahlul, an Afghan of the Lodi tribe, says Tiger’s uncle in his book on the history of the family. Bahlul was governor of the Punjab and later ruled Delhi. A mass migration of Afghans to India took place during his time. Salamat Khan’s family was chosen to quell the Mevati tribe.

Bahlul’s grandson, Ibrahim Lodi, did not trust the Afghan nobles. This led to their rebellion and Babur of Kabul was invited to India resulting in the Battle of Panipat. Ibrahim Lodhi was killed and Mughal rule was established.

Salamat Khan did not actively participate in the Battle of Panipat. His great-grandson, Muhammed Pir, rose to power in Akbar’s court.

In the 18th Century, Alaf Khan of the family assisted the Mughal ruler in his battle against the Maharaja of Jaipur. He was rewarded with Kalam Mahal (which later came to be known as Pataudi House near Delhi Gate) to serve as the family residence.

The princely State of Pataudi was established in 1804 by the British when Faiz Talab Khan (who was made the first Nawab) aided them in their battle against the Marathas. In 1857, the Nawab of Jhajjhar, the Nawab of Pataudi’s cousin, joined anti-British forces and was hanged by the British. The territory was cut in half and Pataudi became a minor State. Cricket placed it on the international map with two generations of players excelling in the game.

Tiger’s mother Sajida Sultan belonged to the well-known House of Bhopal. She became the Nawab Begum of Bhopal after the death of her father, Nawab Hamidullah Khan. Flag Staff House, the residential building of the Bhopal rulers is located within the Ahmedabad palace complex which Hamidullah Khan built in the old Bhopal area. Former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President Rajendra Prasad were State guests here.

This article was published in ‘The Hindu Sunday Magazine’ on August 3, 2003

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Sport> Cricket / by Kausalya Santhanam / September 26th, 2011