Awadh, U.P. / WEST BENGAL:

Calcutta may not have a birthday, but there can be no disagreement that the city is an alchemy of multiple events and influences. One such is the arrival of the ruler of Awadh. Wajid Ali Shah arrived in Calcutta in 1856, remained here till his death in 1887 and continues to tick on in the city’s DNA.

Metiabruz

Before 1856, Metiabruz was a nondescript place on the outskirts of Calcutta taking its name from a matiya burz or earthen tower. The shipbuilding yard of Garden Reach had just started developing. It was the advent of Wajid Ali that transformed the very nature of the place. He purchased land from the King of Burdwan and built around 22 palatial

residences in Metiabruz. With these at the core, an entire mini-Lucknow came up. “He made this city his home and left a legacy, some tangible and mostly intangible,” says Talat Fatima, one of the king’s progeny and currently working on the English translation of the book Wajid Ali Shah Ki Adabi Aur Saqafati Khidmat by Kaukab Quder Meerza. Meerza Sr’s son, Kamran, points to the remnants of the king’s mimic kingdom — Sibtainabad Imambara, Begum Masjid, Shahi Masjid, Baitun Nijat and Quasrul Buka.

Thumri

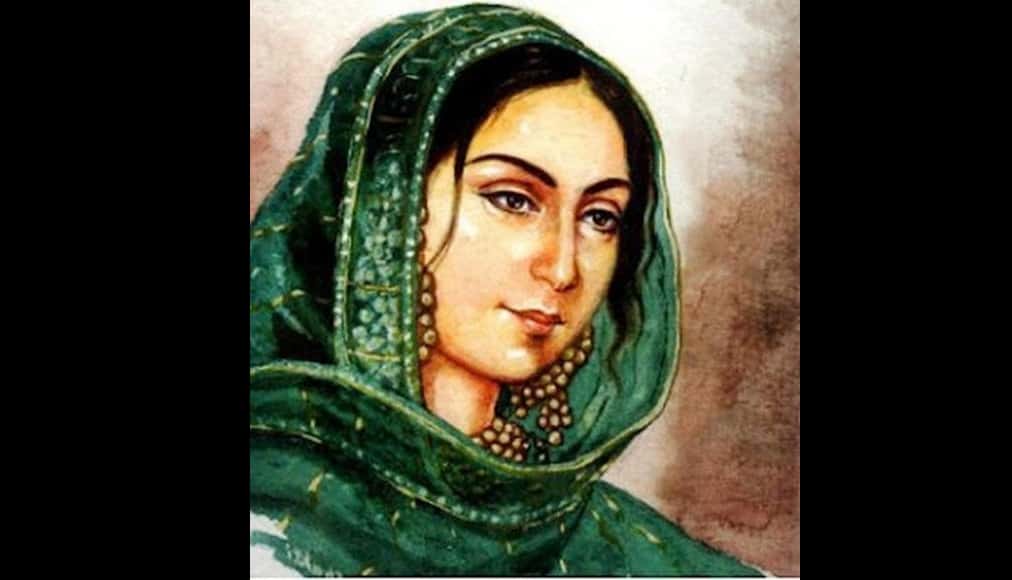

Until the early 19th century, Calcutta’s aristocracy had some exposure to Nidhu Babu or Ramnidhi Gupta’s semi-classical tappa. As for dance, there was the form practised by the khemtawalis of the red-light areas of Chitpore and Bowbazar in central Calcutta. Enter Wajid Ali Shah. He was, historians note, an “enthusiastic” patron of the arts. The “light classical” vocal form of thumri flourished in his court. He himself composed thumris under the pen name of Akhtar or Akhtar Piya. The thumri was traditionally performed by tawaifs or courtesans. And though there are arguments to the contrary, their dance style had “undeniable links” with Kathak. To make a long story very short, the king arrived in Calcutta with his musical entourage, thus stirring into its environs and culture a new rhythm. Courtesans like Malka Jaan were appointed by his court. Other ustads and musicians arrived too and many Bengali-speaking singers such as Bamacharan Bandyopadhyay were also groomed. A new style of thumri evolved with folk influences and it came to be known as the bol banao thumri. The babus of Calcutta loved it. Many of the musicians and courtesans settled down in the Chitpore area of north Calcutta, turning it into a production hub of musical instruments. This legacy, somewhat contagious, influenced commercial theatres and produced musical exponents such as Gauhar Jaan, Angoorbala and Indubala who went on to cut gramophone records and became the first artistes to do so. If Wajid Ali had not left Lucknow nagari, Ray’s Jalsaghar would be missing the jalsa; the sound of Begum Akhtar singing, “Bhar bhar aayi mori akhiyan piya bin…”

Haute Couture

It was not just Wajid Ali who arrived in Metiabruz; he was accompanied by his family, his many wives, dancers, a retinue of specialised servants and tailors. By some estimates, within a decade of his arrival, the palace had 2,000-plus employees and 1,000 soldiers. All of these people needed clothes, as did the king, who loved to dress. In his early 20th century work Lucknow: The Last Phase of an Oriental Culture, Abdul Halim Sharar suggests that the achkan was Wajid Ali’s gift to Indian haute couture. And so the fitted tunic with its stylish necks debuted in Bengal, as did the angrakhas. The king also wore an elaborate cap called the alam pasand. The royal tailors, their pupils and their descendants popularised Awadhi fashion — the chapkan, the churidar, the shararas, the ghararas… Their progeny has now turned Metiabruz into one of the largest tailoring hubs of unbranded garments. None of this would exist if it had not been for the good old trendy king. But for him, homegrown celebrity designers who are synonymous with wedding wear, sherwanis and fancy achkans would have been making patterns on their bottom line today.

Kabutarbazi

The king was famous for his menagerie and also for the thousands of kabutars or pigeons he reared and kept. He employed hundreds of people to look after the birds. Among the varieties were peshawari, gulvey, choya, chandan, shirazi — many fetched from Lucknow. Some of them were trained to perform manoeuvres during flight. “You’ll still find breeders invoking the royal pigeons while making a sell in the bird market,” says Kamran Meerza, the great-great-grandson of Wajed Ali Shah. Many babus of north Calcutta eventually embraced the hobby and pigeon roosts were a common architectural feature in old mansions of the city. The king also brought one of the best kite fliers of Lucknow, Ilahi Baksh Vilayat Ali, with him. He himself could design kites and encouraged others to compete with his team of kite fliers. The tradition of flying kites from those days still survives in Calcutta. Beginning August 15, right through to winter, the city skies are dotted with kites, most of them made in Metiabruz. Kabutarbazi and kite flying are not just random sports, they are synecdoches of a culture of great panache even in great leisure.

The Calcutta Biryani

The king’s khansamas gave Calcutta a taste of the Awadhi style of dum pukht or slow oven-cooking. Their descendants spread across the city and continued to popularise and adapt this style of cooking to fit the plebian kitchen. The Calcutta Biryani would be nowhere on the culinary map had it not been for the banished king. Manzilat Fatima, who is Wajid Ali’s great-great-granddaughter, wields her secret family recipes to create the Calcutta Shahi Biryani and Awadhi Galauti Kebab among other Lucknavi delicacies in her boutique restaurant in south Calcutta. Manzilat clarifies that the potato, an exotic tuber in the 19th century, was used as an experiment by the king to enhance the taste of the biryani and not to incorporate a cheaper substitute as has been suggested. Jab tak rahega biryani mein alu…

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph Online / Home> Culture / by Prasun Chaudhuri / August 27th, 2023