Lucknow, UTTAR PRADESH :

Begum Hazrat Mahal was the last of the official queens of the kingdom of Avadh, or “Oudh” as known to the British imperialists, a large province in northern India.

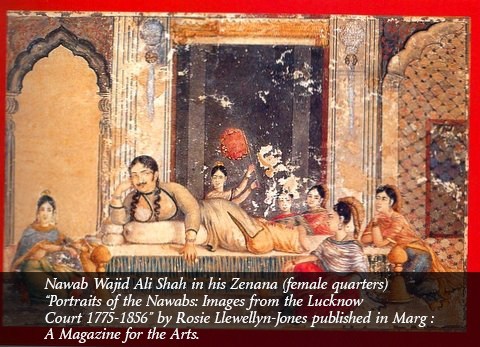

While the details of her birth and family are unclear, it is certain that Begum Hazrat Mahal was not of royal lineage. She is believed to have been a courtesan in the court of the last king of Avadh, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, starting as a dancing girl named “Mahak-Pari” or fragrant fairy. The Nawab, besotted with the young girl, married her by means of the Shiite tradition of “mutah” marriage or “temporary marriage of pleasure.” It was a convenient method by which the Nawabs could add to their harems, and not technically stray from their marriages.

Mahak-Pari, as she was initially known, gave birth to a male child named Mirza Birgis Qadr Bahadur, and was elevated to the title of Hazrat Mahal Saheba, commonly known as Begum Hazrat Mahal. Transforming from a courtesan—a Pari (fairy)—to a Mahal (a royal queen) was rare, and the good fortune of bearing a male child combined with the right maneuvers in harem politics likely helped the young woman.

In 1856, the administrators of the East India Company annexed the kingdom of Avadh, by means of the infamous Doctrine of Lapse. The British coveted this territory as a great resource for cotton and indigo, and appalled by the debauchery of the Avadh court and its gross mismanagement of revenue, preferred to govern the region directly with a more “conventional” administration.

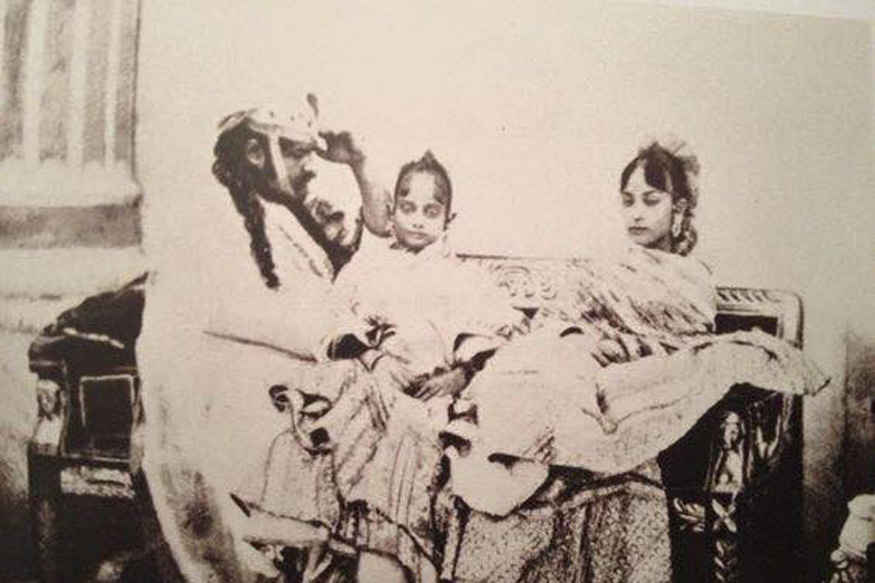

Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was exiled to Calcutta, and the unhappy king left with a few of his wives, and without most of his large harem, including his “secondary” wives. Begum Hazrat Mahal did not accompany the deposed king, continuing to reside in Lucknow with her young son.

When the Mutiny of 1857 broke out, Avadh was one of the major areas of rebellion as several recruits of the army were from Avadh. People were unhappy about the annexation, the deposition of their king, and the religious insensitivity of the British. The rebels needed a leader to further their cause.

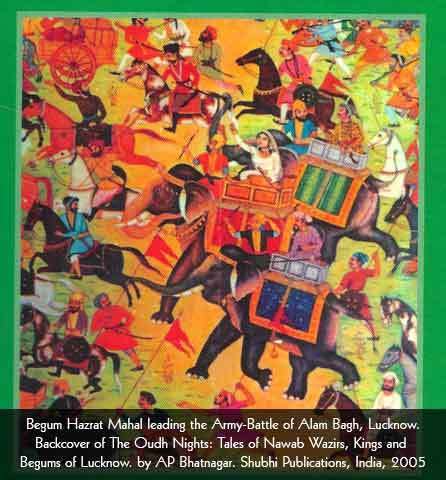

Begum Hazrat Mahal rose to the occasion to help the rebels defend Lucknow against the British troops. To the surprise of her adversaries, she reorganized the army with better co-ordination between the three units of the cavalry, artillery, and infantry. Many times, she rode at the head of the army on an elephant to encourage the soldiers against the advancing British troops.

As in other places, the Indian rebels could not hold out for long against the larger number of British troops, and the queen’s advisors asked the Begum to leave Lucknow in March 1858. She fled to the countryside, continuing her hostilities against the British by issuing orders while in hiding.

On November 1, 1858, Queen Victoria issued a proclamation whose intent was to end the Mutiny, pacify the religious sentiments of the Indians, and formally transfer control of the British territories in India from the East India Company to the British Crown. Begum Hazrat Mahal issued a counter-proclamation in which she argued against every claim of Queen Victoria.

The Begum reminded the Indians that several previous treaties had been violated, that princely heads had either been pensioned or killed, and property worth millions of rupees seized. If the British intent was honorable, why did the British Queen not “restore our country to us when our people wish it?” asked the bold and shrewd Begum. She questioned Queen Victoria’s claim to religious non-interference:

“…to destroy Hindoo and Mussulman temples on pretence of making roads to build churches—to send clergymen into streets and alleys to preach the Christian religion—to institute English schools, and to pay a monthly stipend for learning the English sciences, while the places of worship of Hindoos and Mussulmans are to this day entirely neglected; with all this how can the people believe that religion will not be interfered with?”

Begum Hazrat Mahal forewarned the Indians that their future prospects appeared limited under British rule. “It is worthy of a little reflection, that they have promised no better employment for Hindoostanees than making roads and digging canals.” The Begum’s words were rather prophetic. For decades after 1857, Indians pushed files under British bureaucracy and worked as laborers for the British government in India and overseas.

Begum Hazrat Mahal eventually sought asylum in the kingdom of Nepal, where she lived for the rest of her life. The British administration initially negotiated with her, assuring her a safe return and the possibility of a pension. The Begum, distrusting the British, refused—most likely because British retribution in the immediate aftermath of the rebellion was extremely harsh. While both Hindu and Muslim rebels were ruthlessly punished, there was fear that the Muslims would rise against the British (and Christian power) because it was a hitherto Muslim power that was being displaced, and the repercussions in former-Muslim strongholds such as Lucknow and Delhi were particularly extreme. After their initial negotiations failed, the British labeled the Begum as a woman of “savage disposition.”

Begum Hazrat Mahal has remained a relatively minor figure in Indian history. Her legacy and her heirs were inadequately honored in the centenary celebrations of the Mutiny held at Lucknow post-Indian independence. Her great-grandsons protested against this oversight by the Indian government, which led Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to order an inquiry into her place of burial. Her grave was discovered near Kathmandu, Nepal, in very poor condition. At this point, a park in Lucknow was named after her to commemorate her memory—this park has very recently been renamed—and later a postage stamp was issued in her honor.

Begum Hazrat Mahal’s legacy was diminished in the changed landscape of India post-1857. Her humble beginnings as a courtesan made her an inadequate role model.

The courtesans at the zenith of Lucknow’s court were no petty “nautch-girls” as described by the Victorian sensibilities of the colonists. They were sophisticated women, well versed in the arts of dance, music, and poetry. Their association with the courts made them extremely wealthy and nineteenth-century British records indicate that they were in the highest income-tax bracket before 1857. While the British derided the courtesans, and the culture they espoused, they did not hesitate to tax them on their “ill-earned” wealth. During the Mutiny, the courtesans monetarily supported the rebels, and their homes became rebel hideouts and secret meeting-venues.

Yet, this courtesan culture, the associated decadence and “debauchery” became a source of embarrassment for late-nineteenth-century Indian nationalists, social reformers, and the emerging middle-class English-educated “elite.” Indian nationalists believed that it was decadence and indolence that had helped the British uproot power in the princely states. A strong, respectable people hoping for self-rule needed to identify with respectable women and men, and a former courtesan-turned-warrior-queen did not fit this idealized image.

A strong and resolute woman, the Begum never gave in to the British, while her husband—a good man and an artist at heart, but weak in resolution—continued to live off the generous pension he received, always short of money, and therefore always acquiescing to the British.

Several years after the Mutiny, a British painter visited Begum Hazrat Mahal, in Kathmandu, to paint a portrait of her son, Birgis Qadr. As he worked on his task, the painter ventured to ask her whether she would consider returning to Lucknow. Given the fact that much time had elapsed since 1857, the British regime was willing to forgive her and pay her a pension. Her residence in India would be proof of the British paternalistic spirit of forgiveness. Their condition, however, was that she would not be allowed a lavish lifestyle with a large retinue of servants. Perhaps, surprised by, or suspicious of the offer, but more likely annoyed at the continued interference in her life, the Begum refused the gesture, stating, with true Avadhi andaaz (style) “of what use will be the salary, if I am not to spend it upon the servants?”

Begum Hazrat Mahal was buried in a simple grave in the grounds of a mosque she built. Ironically she named it Hindustani Masjid, after the beloved homeland she had left behind, for whose sovereignty she had fought, and in which she has largely been forgotten.

Aarti Johri is a tech-professional turned history buff. This is an extract from her thesis for the Stanford MLA degree. Her articles have been published in the San Jose Mercury News, Stanford’s Tangents Magazine, and others. She serves on the board of SACHI (Society for the Art and Cultural Heritage of India).

source: http://www.indiacurrents.com / India Currents / Home> Features, General / by Aarti Johri / June 11th, 2016