Motihari, BIHAR :

The author talks about how identity and politics play a huge role in his writing.

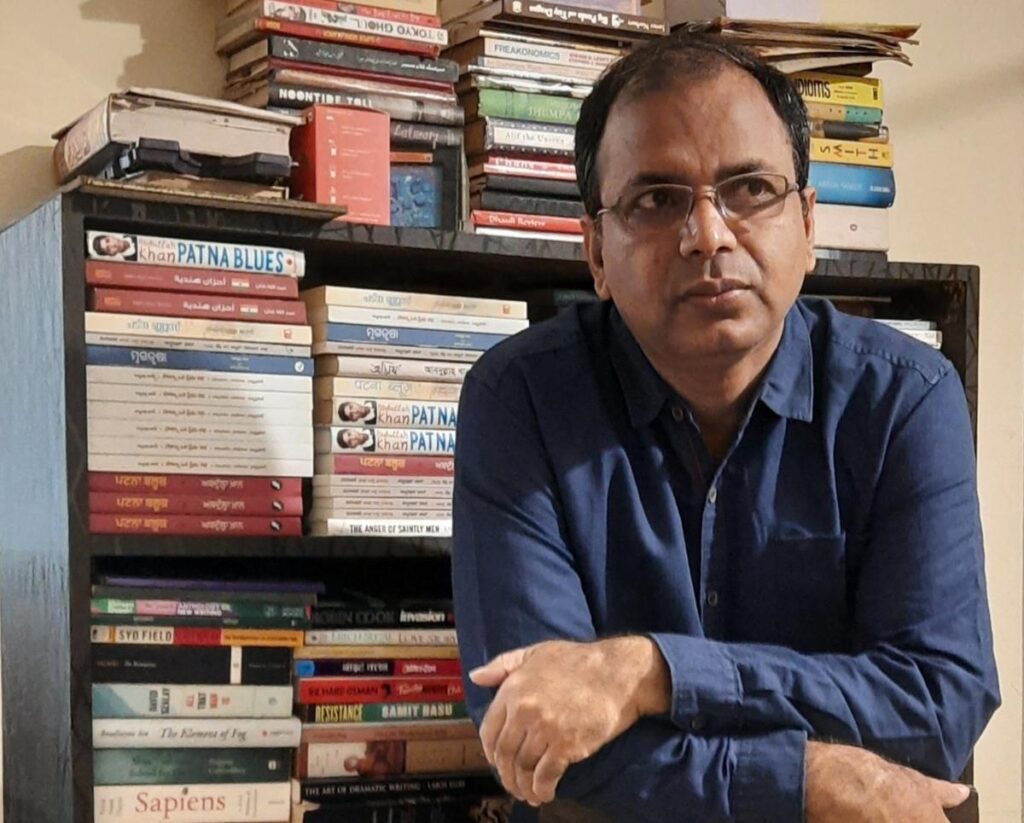

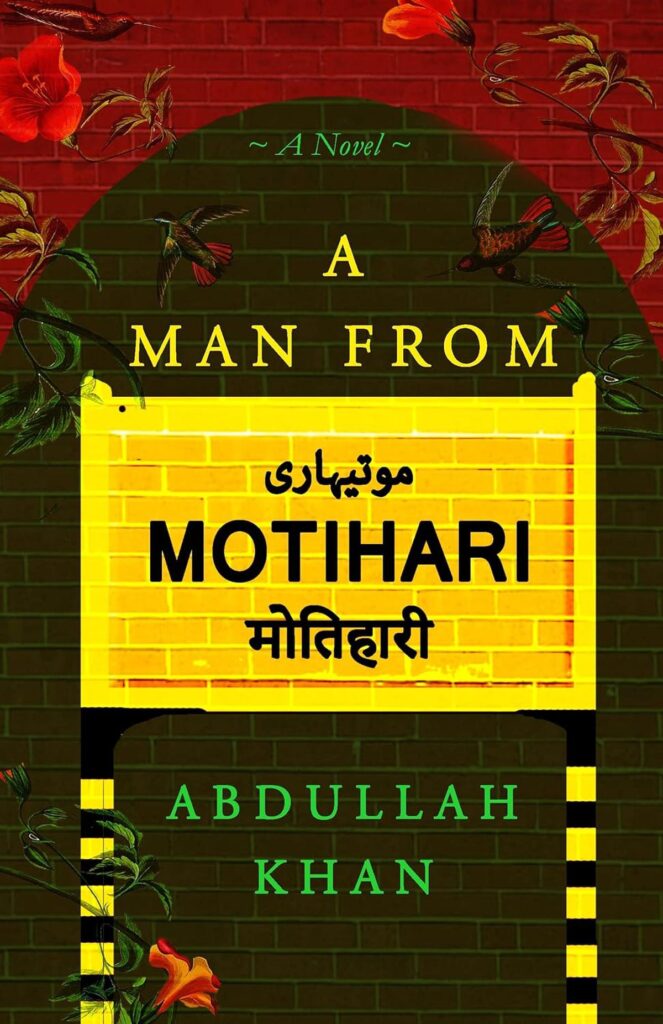

Abdullah Khan’s journey with literature began with a discovery — that he shared his place of birth, Motihari in Bihar, with one of the most prominent authors of the 20th century, George Orwell. Since then, the written word has remained Khan’s constant companion. From his debut novel Patna Blues (2018) to his latest, A Man From Motihari (2023), Khan employs a deft handling of sensitive subjects and hot-button issues to tell stories of everyday characters in Indian society. A speaker at The Hindu Lit Fest 2024 in Chennai on January 26-27, Khan discusses his thoughts on identity, desire and aspiration.

Edited excerpts:

How much of what you write is influenced by your own story?

During my school days in Bihar, my history teacher once asked, “Are you Muslim first or Indian first?” I confidently replied, borrowing the answer from my grand uncle: “I am both, born to Muslim parents, I’m Muslim; born in India, I’m Indian. Both identities came to me at birth.” As a boy, I didn’t fully grasp the complexities of identity.

During college, I pondered over how identity shapes thoughts, realising we’re not always aware of every facet of our identity. Sub-identities and super-identities emerge, revealed by others’ prejudices. In my village, I was Pathan; in school, a Muslim. Beyond Bihar, a Bihari. These identities intrigued me.

As I ventured into fiction writing, my reflections on identity seamlessly became woven into my stories. And, conflict between circumstances and desire is integral to human existence and is a vital element in crafting engaging narratives. I found inspiration in Bihari IAS/ civil services aspirants, news, historical incidents, real-life characters, beautiful places, and even SMS/ WhatsApp forwards for plot ideas.

What comes first — the plot or the point it makes? And in the case of ‘A Man from Motihari’, what was the genesis of the story?

Plots and characters naturally come to me without any preconceived plan. As I create the story, some significant points or messages often emerge organically.

Take, for instance, the inspiration behind A Man from Motihari. A few years ago, a Bangladeshi newspaper asked me to write about the house in Motihari where Orwell was born. While standing in front of that house, I had an idea: what if a boy from Motihari is born in the same room where Orwell was born many years ago? How would the boy react when he finds out, and how would it change his life? That’s how I came up with the character of the protagonist, Aslam Sher Khan, who is born in the same house as Orwell.

Tell us about your journey — from writing to publication.

Fresh out of completing my Master’s in chemistry, when I began writing Patna Blues, I had no knowledge of the technicalities of fiction writing and no background in literature. So, writing Patna Blues served as a kind of training for me, a sort of MFA, where I learned everything from scratch through trial and error. It took almost 10 years to write and nearly 9 years to get it published. I didn’t have a peer group then for beta reading or sharing comments. The journey to publication was challenging, enduring more than 200 rejections before it was published.

For my second novel, it took no more than a year to write, and finding a publisher was comparatively easier. Style-wise, I have improved significantly and gained more confidence in my writing.

There are strong political notes in your stories. What kind of responsibility do you feel towards your readers in terms of what you write about?

I believe no story exists in a vacuum. I allow the politics of the time to become a part of the narrative as I believe it is the only way to tell authentic stories.

While writing about politics, I do not shirk my responsibility as a writer and chronicler of the truth. I strive to be as impartial as possible. I generally don’t allow my personal beliefs or political ideology to creep into the story. Instead, I focus on the characters’ take on the politics of that time and keep myself a bit distant from those events.

What’s your take on literature festivals? What can they do for writers, and their readers?

Literature festivals offer writers a chance to share ideas. They gain inspiration and build a community, while readers enjoy insights into the creative process. As writers, we also get a chance to meet authors from all over the world, and learn from each other.

I think we should do more at these festivals for aspiring authors, like arranging pitching events or conducting writing masterclasses.

I have also observed a disturbing trend at many literature fests, where organisers invite celebrities such as film stars or cricketers to boost attendance. This often shifts the entire limelight to them, sidelining writers.

Gsquare Group presents The Hindu Lit Fest 2024 in Association with NITTE Education Trust & Christ University. Bookstore partner: Higginbothams

swati.daftuar@thehindu.co.in

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Litfest> The Hindu Litfest 2024 / by Swati Daftuar / January 05th, 2024

.jpeg)

.jpeg)