Ramgarh, JHARKHAND / NEW DELHI:

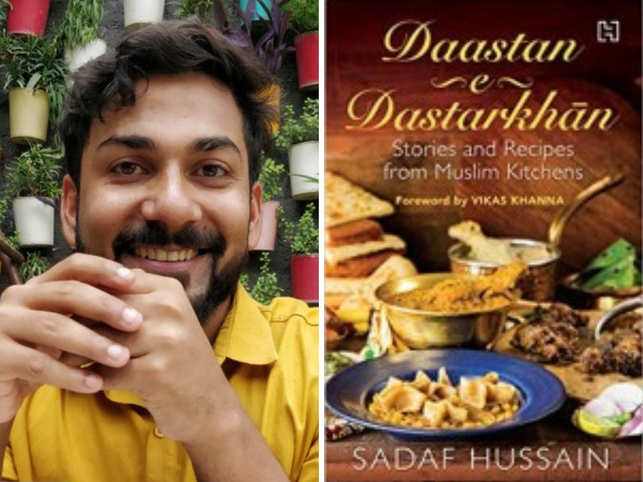

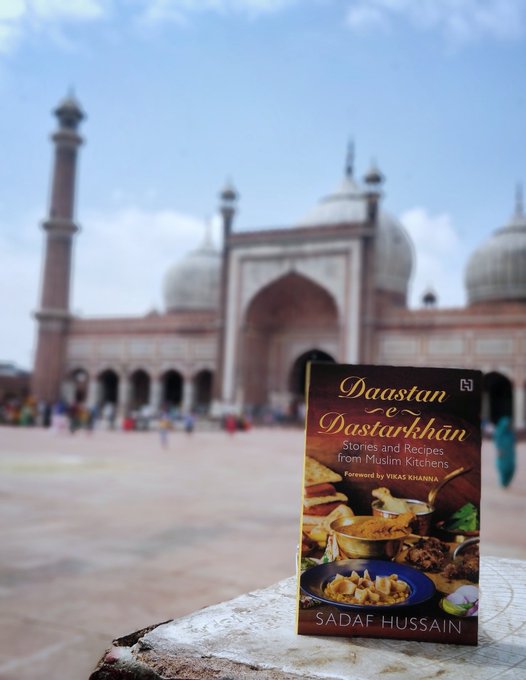

“Sadkon Par Sheharoan ki Rooh Basti hai” (it is on the streets where the essence of the city lies), says Sadaf Hussain, a chef and an author of the book Dastan-e-Dastarkhwan. On a given weekend, Sadaf can be found exploring the food joints in Delhi. Sidelining all the rumours of his roots to Rampur’s erstwhile Nawabs, Sadaf says, “As much as rumours are alway welcomed I am just a fan of Rampur foods, my paternal grandfather may have been something but otherwise we are mango people..(aam aadmi)..”

Sitting on his couch comfortably at his home in Noida, while sipping “adrak-elaichi chai” (ginger-cardamom tea) he spoke with Awaz-the Voice on his journey to fame. Sadaf’s Instagram handle says he is a “khansaman” and he explains this.

“Khansamans are considered gourmet chefs who are known for making very specific portions of food, Khansaman is basically someone who is not trained at a culinary school he learns from their family, parents and so on, it could be as simple as learning how to make kababs or something basic like chopping onions. Similarly I have never been to a culllinary school, I have learned it from my parents, from the golgappa (Crispy fried semolina-wheat balls filled with onion, chickpeas and spicy water) vendors of my street, that is what made me interested in food and that is why I call myself a Khansaman.“

Reminiscing his childhood Sadaf says, “I wanted to be the fattest kid on earth”, this because he was and still is a foodie. Speaking about his childhood days, Sadaf told Awaz-the Voice since the school was just 10 minutes away from his home he was fed like a king daily, his motivation behind attending school was to get good food,“School wese bhi koi padhne ke liye nahin jata hai, na hi hum jaate the (I wonder whether anybody attends school to study, neither did I). I used to go to school to eat food, not midday meals. School used to get over by 10. Thus a normal weekday in my life included a breakfast at 7 then recess at 9 and after coming back home a good hearty lunch, thus in a span of 4-5 hours I ate 2-3 times…”, he laughs loud.

Why he has a name that is generally given to girls? “My mother wanted a girl child, and she did a lot of experiment on me. It is because of her that I am very much in touch with my feminity, in our home, we just had our mother as a female figure, I was 8-9 years old and my mother got paralysed; My parents always worked as a team, I have always been into food, cause I grew up with food makers…”. Sadaf proudly says,

“I am glad I broke the age-old custom of women cooking food, serving men and eating last, at my place I make food,serve all and eat last..”.

Sadaf has studied advertising from St.Xavier’s, Ranchi, Jharkhand. He worked in the media industry In 2015 he started the culture of pop-up cafés in Delhi, “We did it in home and invited friends over where they got to meet each other, every month we cooked European cuisine though I love eating Indian food. We made pasta, spaghetti and other stuff. I always loved cooking for people and of course needed validation..”

In 2016, Masterchef India happened to him and he ended reaching the final round. “I have a philosophy of life – try everything, for one has nothing to lose, try toh karo nahi mila toh koi na, pehle bhi kaun sa tha hi. With this in mind, I entered the Masterchief competition. Those were Ramzan days and i presented the food to the judges without tasting it. We were shooting in Udiapur, Rajasthan. I saw these stars (Top-Ranking Chefs) for the first time…”

Haling from a small town Ramgarh in Jharkhand, it was a dream come true moment for Sadaf, “When you come from a different class and a different area simple and small tasks look big, thus this platform altogether was surreal..after that the environment really pushed me to do bigger things…While I was there, I was thinking chalo office se ek hi din ki chutti hogi (it’ll be a day off from the office) but somehow it was more than that…”; he adds, “one day Chef Vikas (Khanna) called and asked me: Why are you here? I told him that I don’t know but yeah I do know that I am not there to become a celebrity but if I win, 10 log jaante the pehle ab shayad 50 log jaan jayenge, log jane mujhe, mere hunar ko jane bas yahi kafi hai (Earlier 10 people knew me now maybe 50 would, I just want people to know my skill)…

Hussain says after the Masterchef he didn’t want to carry his identity everywhere as he didn’t want just one thing to define him, “I wanted to ditch my identity from Masterchef as I wanted to be something more than that,Meri haisiyat and aukat yeh nahin hai ki mai khud ko Masterchef bolta, mai nahi hu Masterchef, mai chef hu, lekhak hu (I am not worthy enough to be labelled Masterchef).I am an author, I am a chef ..”

Talking about the democracy involved in food and the difference between Diwan-e-Aam (House of Commons) and Diwan-e-Khas (House of Royals), Sadaf believes that the rich will always have a bigger table and more food dishes, “Think about it this way, when we are in college we just avoid any kind of parties, when we start earning we start eating better and at times our platter increases from noodles to spagetting and then maybe we start exploring cuisine, but for those born with a golden spoon they always have a spine…”.

“I believe taste evolves with time, earlier the Nawabs used to employ dieticians who supervised simple and non-simple foods, from Nahari to Murgh-Mussallam. Royals used to add dry fruits in every dish, today I think anything that one can afford is aam (commons) and rest everything is Khas (special)..”

He says that any food becomes Shahi (royal) when served with dry fruits and saffron, even a simple milk tea would be termed royal if these ingredients are added. He says the manner in which the food is prepped is democratic, “a Hindu, Muslim and Dalit will make it differently, cause of their backgroud also the usage of Ghee…”

When asked about the disparity among the food he says, “There is disparity and there will be always be disparity, sablog ek level pe ni a skte (not everyone is at the same level), but democracy for me would be if everybody can cook basic food and of course dal-chawal, chicken, rice, curd, ghee, mustard oil and so on are a staple in any cuisine that is democracy…”

“…not everybody can use cheese in their cooking, I feel the rich create demand in the society and then people start using it…for example Blueberries, if the demand is more the supply would increase and prices would go down..but yes basic nutritious food is something that everybody should be able to afford

He told Awaz-the Voice that every century the ruler has tried to maintain a food democracy…food eating habits are the easiest way to make people surrender to food as it is something everybody should be able to afford, “organizations like the UN are trying to make food affordable but then it is a policy-level discussion, the ration system is one way to democratize food but I believe food shouldn’t be available for free, it should be worth something cause then the wrong message sets deep in the psyche..”

Sadaf has recently worked upon a project called The forgotten foods of Rampur, “Dr Tarana Hussain, (author) is responsible for this project, along with Siobhan YH (historian). It was her professor at the University Prof Dunc Cameron who asked her to pursue this project..I was hosting a pop-up cafe one day and that is how I stumbled into Tarana, she was looking for people who were practioners and wanted to document food..thus I became a part of the project…”

Mentioning Rampur’s cuisine Sadaf says, “Urad dal ki khichadi served with Gobhi gosht or Saag ghost and of course mooli Ka achar..then there are kababs, ghalawati kababs, qorma and much more.

On the history of food documentation, Sadaf says, “documentation of food started really late..I think it was Ibn-e-Batuta, Marco Polo who started documenting food”.

He says Qorma is different in every state, from Rampur to Lucknow, Hyderabad gravy or Salan as we call it will be prepped in a different manner. On the history of food, Sadaf says that when potato was discovered, it was ridiculed and even considered bad for health but then there were so many wars happening and though it is not Indian, it is cheap and a like chameleon, Potato can take the flavours of every curry, “from sweets, to Vodka to Biryani, it is multifaceted..”

Talking about similarities in cuisines of the world, Sadaf says, “Every country has Dumplings and Cheese..”

On asked to explain he says, “Everybody used to have veggies, milk and meat and off course people started inventing different ways to utilize and preserve it. Thus different ways of cheese were made, “Kalari cheese is prepped in the mountains while Bandel cheese in Calcutta, Cheese of Bombay is called tapela…”

Coming to dumplings and custard he say, “they are very easy to make and then they can be made in a different ways from Momos to Modak to Phare to Litthi..all are versions of stuffed dumplings while custards or kheers are another very basic version of milk puddings..”

Winding off Sadaf says, “Breads I believe are Panch Poorats, as they are made of five elements—fire, earth, air, water, space…”

source: http://www.awazthevoice.in / Awaz, The Voice / Home / by Shaista Fatima / January 24th, 2023