DELHI :

- The reign of Shah Alam, one the last Mughal emperors, was upturned by the Rohilla chief Ghulam Qadir

- The vengeful treatment of the emperor caused such outrage that even the Afghan king offered to send aid

In August 1788, the Red Fort in Delhi witnessed what one observer would recall as the most “unspeakable and indescribable” crimes. As in the previous year, the Rohilla chief, Ghulam Qadir, had descended on the Mughal capital, threatening to unleash chaos. While his last attempt had been aborted, thanks to Begum Samru, a dancing girl turned princess, nobody rode to Shah Alam II’s rescue on this occasion. In fact, the officer in charge of the fort, despite orders to the contrary, threw open its gates, and 2,000 of Ghulam Qadir’s troops quickly took charge of the premises. Secure, the warlord made his way to the audience hall. And there, as William Dalrymple recounts in his splendid new book, The Anarchy, he “sat down on the cushions of the imperial throne”, blowing smoke from a pipe into the face of the badshah of Hindustan.

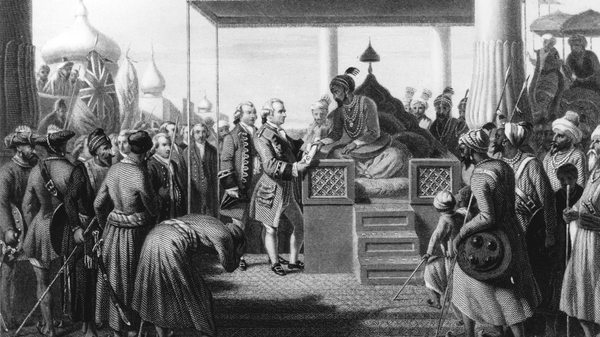

Shah Alam had not had a particularly glorious career, but even with its general turbulence, this was unprecedented. It was decades since the empire of the Mughals had begun to unravel, but while the emperors had been reduced to ciphers, their dignity had never been so insolently offended. Shah Alam had tried in vain to reclaim power for the crown: For over a decade, he was not even in control of his capital, and, during his peregrinations, was forced (after military defeat) to grant governorship of the empire’s richest province to the East India Company (EIC). In 1772, he finally returned to Delhi, his general Najaf Khan bringing order to the surrounding regions. When the latter died, the Marathas stepped in to supply protection. For all his outward marks of authority, though, this came at the cost of giving free rein to Shivaji’s political heirs. As the contemporary chronicler Prem Kishor wrote, “The king (had) abandoned his sovereignty and taken up the ways of beggary.”

As a man, Shah Alam was not, to be clear, all incompetence, but, as scion of the Mughals, he inspired little support. He was a poet of talent, writing verses in languages as diverse as Braj Bhasha and Persian. EIC officer Col Polier described him as “a good and benevolent man” so far as his private characteristics went, but acknowledged that he was not by any stretch a “great king”. The English governor Warren Hastings, who refused to remit even the share of Bengal revenues that were due to the emperor, was more blunt: Shah Alam was merely a “wretched King of shreds and patches”.

And, as Dalrymple reminds us, while others in theory paid homage to the crown, Tipu Sultan discarded even this pretence. Those who bowed before Shah Alam, announced Mysore’s sultan, “act through ignorance, since the real condition of the so-called Emperor is…(that he is) the servant of (the Marathas) at the monthly wages of ₹15,000″.

And yet for all this contempt, Ghulam Qadir’s actions in 1788 sent shockwaves down the entire subcontinent: As the colonial-era historian W. Francklin wrote, to this man “it was reserved to…add the last outrage to the miseries of a long and most unfortunate reign”. The sequence of events that confirmed the Rohilla as one of the worst villains of the 18th century is chilling. Soon after taking charge of the Red Fort, Ghulam Qadir had Shah Alam locked up, planting in his place another prince on the throne. But what the trespasser really wanted was gold, not empty titles and grants of land, and none of the coin heaped before him satisfied the demand. Old begums were dispossessed of their jewels, and even the officer who opened the fort gates paid up—threatened that he would be drowned in excrement, the latter surrendered his own money to escape this revolting fate.

Furious, Ghulam Qadir turned on the imperial family, which for all its bloody intrigues had never quite experienced what he now decided to unleash. Princes of royal blood, including sons and grandsons of Shah Alam, were dressed in drag and made to dance for the Rohilla troops. The emperor’s daughters were stripped, raped and humiliated. Even Malika-i-Zamani, the formidable widow of a previous emperor, Dalrymple writes, was left naked in the hot sun after failing to deliver to Ghulam Qadir the riches he believed she possessed. And finally, bringing to his presence Shah Alam himself, the “ferocious ruffian” had the emperor blinded. In some accounts, in fact, he sits himself on Shah Alam’s chest, scooping out the old man’s eyes with a dagger.

Theories abound on Ghulam Qadir’s diabolical ferocity. His father had rebelled several times against Delhi, and, after defeating him, Shah Alam had taken Ghulam Qadir, then eight or 10 years old, hostage. One apocryphal tale says that after seeing the uncommonly handsome boy, the emperor had him castrated, often making him dance in women’s clothes. In an account left behind by a disgruntled Mughal prince, there is a suggestion of something beyond a regular relationship between Shah Alam and the Rohilla boy. Even as the emperor described Ghulam Qadir as his “special son”, wishing him great happiness in his poems, this contemporary noted that the boy suffered from ubnah, or “an itching in his behind”, hinting that he was made to serve as the emperor’s catamite. This, more than mere ambition or greed, it is believed, explains the horrors Ghulam Qadir let loose in 1788 on Shah Alam and his children.

But the act was for the Rohilla a death sentence. The treatment of the emperor caused such outrage that aid was offered even from Kabul. The Maratha general, Mahadji Scindia, led a large force to Delhi, and while Ghulam Qadir escaped, he was cornered and captured in Mathura very soon. Placed in a cage, his ears, nose, lips and feet were cut off, one by one, each of these circulated in the Red Fort by the emperor. And finally, the story goes, Shah Alam, in whose reign the Mughals lost their final vestiges of power, received one last box, holding within it Ghulam Qadir’s eyes.

Medium Rare is a column on society, politics and history. Manu S. Pillai is the author of The Ivory Throne (2015) and Rebel Sultans (2018)

source: http://www.livemint.com / Live Mint / Home / by Manu S. Pillai / August 30th, 2019